The overthrow of Hosni Mubarak's regime in Egypt last year served as dramatic proof that the Arab Spring wasn't just a passing, or purely Tunisian, phenomenon. Egypt's revolution heralds the coming obsolescence of the late-20th-century-style militarized pseudo-democracy in the Middle East, and its influence has extended as far as Wall Street's Zuccotti Park. Future generations will surely study Tahrir Square and what happened there intensively, but anyone in search of an expert account today need look no further than Ashraf Khalil's "Liberation Square: Inside the Egyptian Revolution and the Rebirth of a Nation."

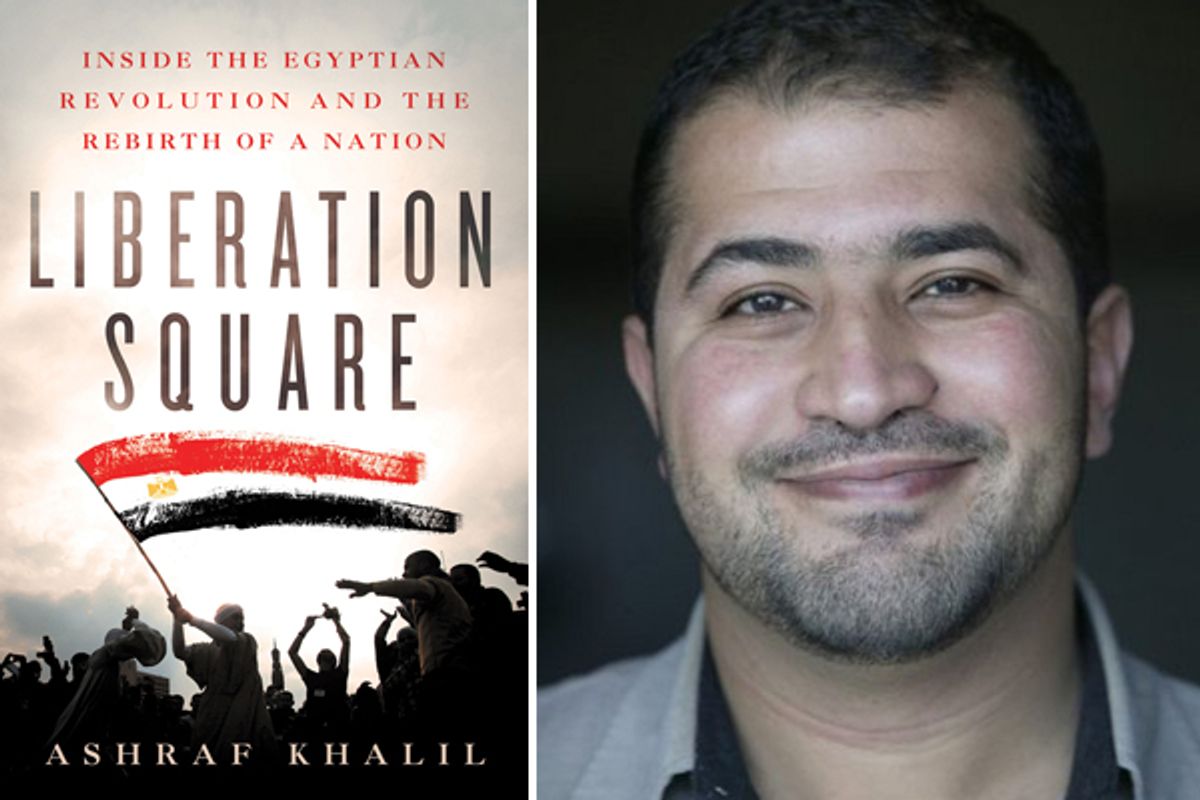

Khalil is a Cairo-based journalist who reports on the Middle East for a variety of Western publications. While it's impressive that he has published "Liberation Square" before the one-year anniversary of the uprising, it's not unusual. Reporters routinely crank out quickie books on major news events, and these tend to be rushed and lumpy creations, nearly as ephemeral as the newspaper stories on which they're based. What's remarkable about "Liberation Square" is how good it is, how well written, how perfectly calibrated in its amounts of background, commentary and prognostication -- and above all how thrilling it is to read.

"Liberation Square" is also far from impartial, though I doubt there are many readers who will fault it for that. As a longtime Cairene, Khalil is able to quickly and vividly sketch the mindset of his countrymen as, a mere year ago, they faced the demoralizing prospect of Mubarak's son, Gamal, continuing his father's nepotistic, kleptocratic style of governance into the foreseeable future. He knows the jokes they told and the shame they felt -- as a nation of famously "clever, resourceful and resilient" people, inheritors of an ancient and storied civilization -- at being dominated by a pack of bullies, liars and incompetents.

In describing the increasingly intolerable conditions in Egypt, Khalil picks out a few cultural and political milestones and symbols that capture this malaise and festering disgust. The buddy comedy movie, "Cultural Film," about a group of friends desperately trying to find a place to watch a softcore video, portrayed the bottled-up sexual frustration of a generation of educated young men who had no hope of ever finding decent jobs, moving out of their parents' homes and getting married. A bestselling novel, "The Yacoubian Building" (later made into a film), uses "a grand old building in downtown Cairo" to illustrate how the rigid Egyptian class system arbitrarily yet mercilessly dictates the residents' fates.

And then there's the Internet, whose role in the uprising was, Khalil confirms, pivotal. Two important figures were Khaled Saieed, a 28-year-old Alexandrian computer buff, who was beaten to death in a foyer by police officers for reasons unknown. A relative used a cellphone to secretly snap a photo of Saieed's battered corpse, and this, along with the victim's fresh-faced, quintessentially middle-class passport photo, "exploded onto the Egyptian Internet," inspiring a We Are All Khaled Saieed page on Facebook. "The huge thing with Khaled Saieed wasn't his picture after he got killed," a blogger told Khalil. "It was his picture before he got killed. A little innocent-looking guy who looks just like your son, your cousin, your nephew. That's what galvanized people."

Another galvanizer was Asmaa Mahfouz, a 26-year-old veiled woman who took to YouTube to harangue the populace into attending the Jan. 25, 2011, protest in Tahrir Square, provoked by the flagrantly rigged elections of the previous year and the electrifying example of the Tunisian revolution. "Mahfouz directs more of her anger at her fellow Egyptian civilians than at the government and the police," Khalil writes, "taunting viewers to prove their manhood" by showing up at the square. Aimed as it was at the Egyptians' "prized self-perceptions of what it meant to be a man" and providing more traditional women with an activist role model, this and other Mahfouz videos constituted "a remarkable moment of viral political marketing," Khalil writes. Her impact, he asserts, was enormous.

The last half of "Liberation Square" forms a suspenseful, day-by-day narrative of the weeks between that first protest, on Jan. 25, and Mubarak's resignation on Feb. 11. Khalil was on the streets much of the time and has interviewed dozens of participants about the unfolding drama as the demonstrators sought to take bridges and public spaces from the police, figured out how to communicate when the government cut Internet and cellphone service, fended off attacks from hired Mubarak supporters on camel- and horseback, welcomed the military and then wondered why it didn't do more to defend them, listened to and rejected the self-justifying statements of Mubarak and other officials, and gradually realized that there was no going back and that the country was theirs at last.

Khalil is responsible enough to outline the ways that "figuring out what comes next will be much more difficult" than jettisoning Mubarak. The new Egypt must cope with a press so accustomed to toadying to the government or private owners that it doesn't know how to think for itself, and with old-school elites doing everything they can to make sure they're not held accountable for their misdeeds. Will the army, which is currently running the government, surrender that power willingly? How can decades of corruption and cronyism be replaced by a more "meritocratic" society, a reform that Khalil regards as "the single most important change going forward"? Although "Liberation Square" does offer a satisfying resolution in the form of Mubarak's ouster, it's a resolution for the book, certainly not for Egypt itself. There, the protests continue.

Shares