So far, the Republican primaries have been a decidedly unsexy affair. Candidates have passionately spouted rhetoric against premarital sex, gay sex -- even non-procreative sex within marriage. It's enough to make you wonder if the country has gone to the prudes.

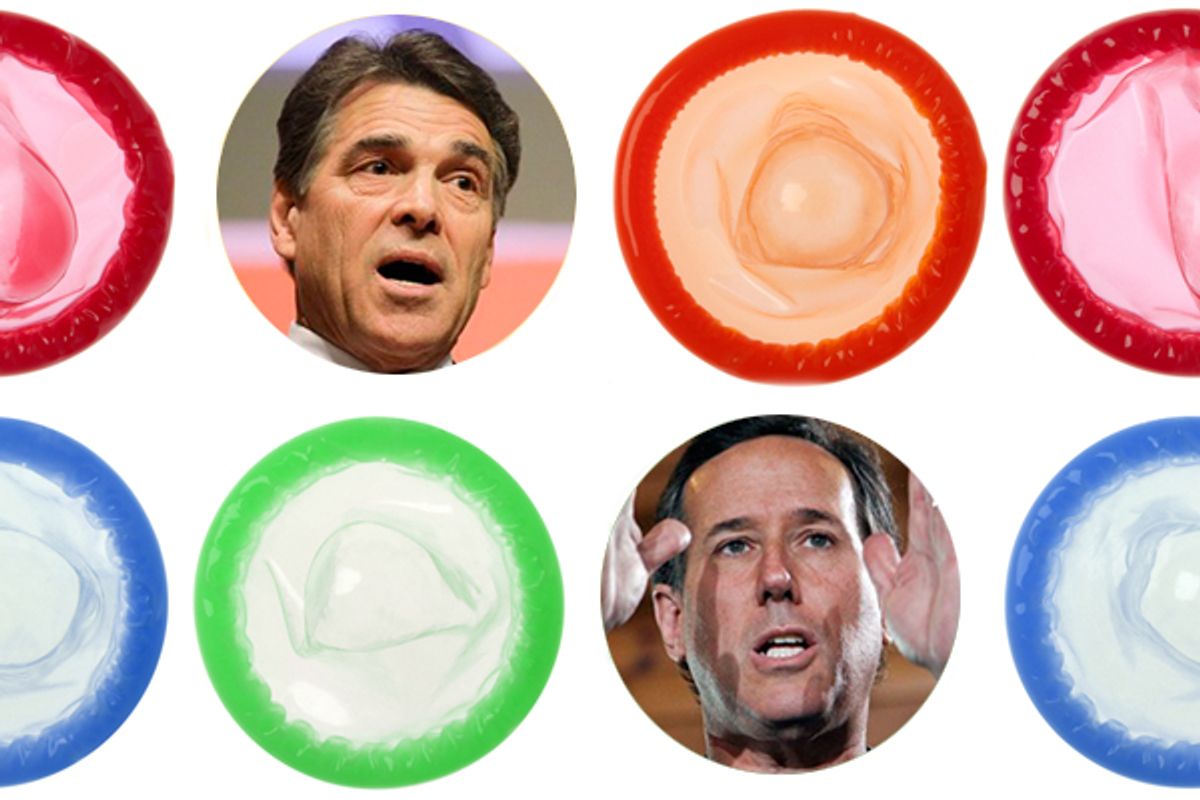

Rick Santorum, who has compared gay sex to bestiality, outdid himself in an interview that resurfaced this week in which he suggested that states should have a right to outlaw birth control since contraceptives are "a license to do things in a sexual realm that is counter to how things are supposed to be." The other Rick, former Texas Gov. Perry, has been an outspoken opponent of gays in the military and the "sin" of homosexuality. Recent dropout Michele Bachmann seemed a messenger from a previous era, what with her belief that homosexuality is "personal enslavement" and her pledge to ban pornography.

Anti-sex rhetoric is hardly new to the Republican Party, of course, which has routinely campaigned to increase the dangers and consequences of sex by restricting access to contraceptives and abortion. But the GOP war on sex also comes at a time when the party's presidential candidates have perhaps never been more out of step with the sexual beliefs and practices of most Americans.

"The private sexual behavior of all ages, of all political persuasions is getting more liberal," says Marty Klein, a sex therapist and author of "America's War on Sex." "It's going toward more variety, more partners, more kinky sex, more experimentation and, as the age of first marriage goes up, by definition the amount of premarital sex is going up." Indeed, "the vast majority of Americans have sex before marriage," according to a Guttmacher study, and most believe that out-of-wedlock nookie is morally a-OK.

We see the same story when we look at sex-related policy. The majority of Americans favor national recognize of same-sex marriage and most say same-sex relationships are morally acceptable, although there is a partisan divide, with only 23 percent of Republicans favoring legalized same-sex marriage. Santorum's stance on birth control even conflicts with that of most Catholics. Dan Cox, director of research at the Public Religion Research Institute, tells me, "In our own polling we find close to 90 percent [of Catholic women] are in favor of expanding access to birth control for women who can't afford it and this is true among most religious groups and political groups."

What's more, 99 percent of Americans who have ever had sex have used some sort of contraception. Nowadays, most Americans want abortion to be legal (while also harboring moral concerns about the practice).

All of this raises the question: Why are the GOP's leading candidates becoming more sexually conservative as the rest of America heads in the opposite direction? How are the remaining prudes so good at filibustering the rest of us?

"For years we've been told 'it's the economy, stupid.' Iowa showed that 'it's the sex, stupid,'" says historian Nancy L. Cohen, author of the upcoming book, "Delirium: How the Sexual Counterrevolution Is Polarizing America." "Iowa should put to rest the myth that social issues are unimportant. It's easy for Republican voters to tell pollsters that the economy is their most important issue. But that's only because every candidate has promised the radical anti-abortion and anti-gay activists the world."

It isn't just Iowa, though: Even as we increasingly disown notions of procreative marital sex as the only legitimate form of sexual experience, "the public policy around sexuality is getting more conservative, more draconian," aside from tremendous progress within the gay rights movement, says Klein. "That schizophrenia has been in evidence since the day that George Bush took office -- you could even say since the day that Bill Clinton was impeached."

Dagmar Herzog, historian and author of "Sex in Crisis: The New Sexual Revolution and the Future of American Politics," traces it back even further. She argues that "the attention Santorum is getting today for his extreme views is part of an extended, decades-long backlash against women’s freedoms, sexual and otherwise."

It's a backlash that Cohen refers to in her book as "the sexual counterrevolution."

Posner sees it only becoming stronger: "It's as if the more states in which gay marriage becomes legal, the more they push back against it. You see them more visibly in the public square now. The Republican Party for the last 30 or so years has depended on the support of these religious conservatives at the polls, so they've cultivated those religious conservatives during the primaries -- and a couple of the early primary states are very heavily influenced by religious conservatives."

Posner calls this "the dilemma of the Republican Party right now. It's such a big part of their base that they can't win without talking about these issues."

Rhetoric against birth control and premarital sex appeals to the moral convictions – if not always the actual actions or policy beliefs -- of the evangelical right. Dan Williams, author of "God's Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right," says, "I don't think that evangelicals want to see birth control made illegal, but I also think that many evangelicals will respect Santorum for having the courage to say what he believes, and they will appreciate his opposition to what they perceive as a culture of sexual promiscuity," he said.

Republican voters, especially evangelicals, have been trained to listen for candidates' "dog whistles" -- language that goes over the heads of those who aren't listening for it. They're especially attuned to code words.

"People read Republican policy statements metaphorically," Klein says, "so people are reading Rick Santorum [saying he's] against contraception, the way people code that is, 'Oh, he's in favor of containing sexuality and not having people use sexuality in a bad way.' The small detail of, you know, that you might not be able to walk into a drugstore and get condoms without showing an ID? That just goes over people's heads."

The right-wing of the Republican Party, he adds, is extremely adept at "talking about emotions, feelings, the subjective emotional experience of people. When they talk about sexuality, people are hearing, 'Yeah, I'm worried that my 14-year-old is going out into a sexual world that seems to have no boundaries whatsoever.'"

Let's be honest, though: Religious conservatives aren't the only ones who fall for the anti-sex rhetoric. Klein points out how fear-driven American politics has become: "It's a way of getting money -- nobody gets public money if somebody is slightly annoyed. You have to be terrified." And sex freaks people out like nothing else, regardless of political persuasion.

"It does remain a puzzle why it has been so hard for Americans loudly to defend sexual rights even if they definitely enjoy having them," says Herzog. "This creates an echo chamber in which the bullies get to set the terms of debate."

Klein argues that "the normal pushing and shoving, pluralistic conflict-driven politics doesn't work when it comes to sexuality" because few people are willing to speak up in defense of their private sexual practices. "If the government says, 'We're gonna ban hot dogs,' everybody stands up and says, 'Hey, I eat hot dogs, don't do that!'"

With sex, however – whether it's reproductive rights, censorship of porn or prohibitive zoning laws for adult businesses – things are different.

"Every time it's about sex, we're going in with one hand tied behind our back – and not in a good way."

Shares