Almost 13 years ago, attendees of the Sundance Film Festival left the midnight screening of a low-budget horror film called "The Blair Witch Project" and gulped in the cold Utah air, shaken and invigorated. “The lucky ones who saw it at Sundance,” Michael Atkinson wrote a decade later, “not knowing a thing about it, at the legendary late-night showing and then (emerging) into the mountain nighttime, could make millions bottling that experience.”

The big studios certainly figured that out. This weekend, the faux documentary "Devil Inside" confounded expectations by grossing $34 million in its first three days -- topping the box-office charts despite being trashed by critics (7 percent fresh on Rotten Tomatoes) and audiences (a CinemaScore rating of F). It's the third-best January opening ever -- and the film only cost Paramount $1 million to make.

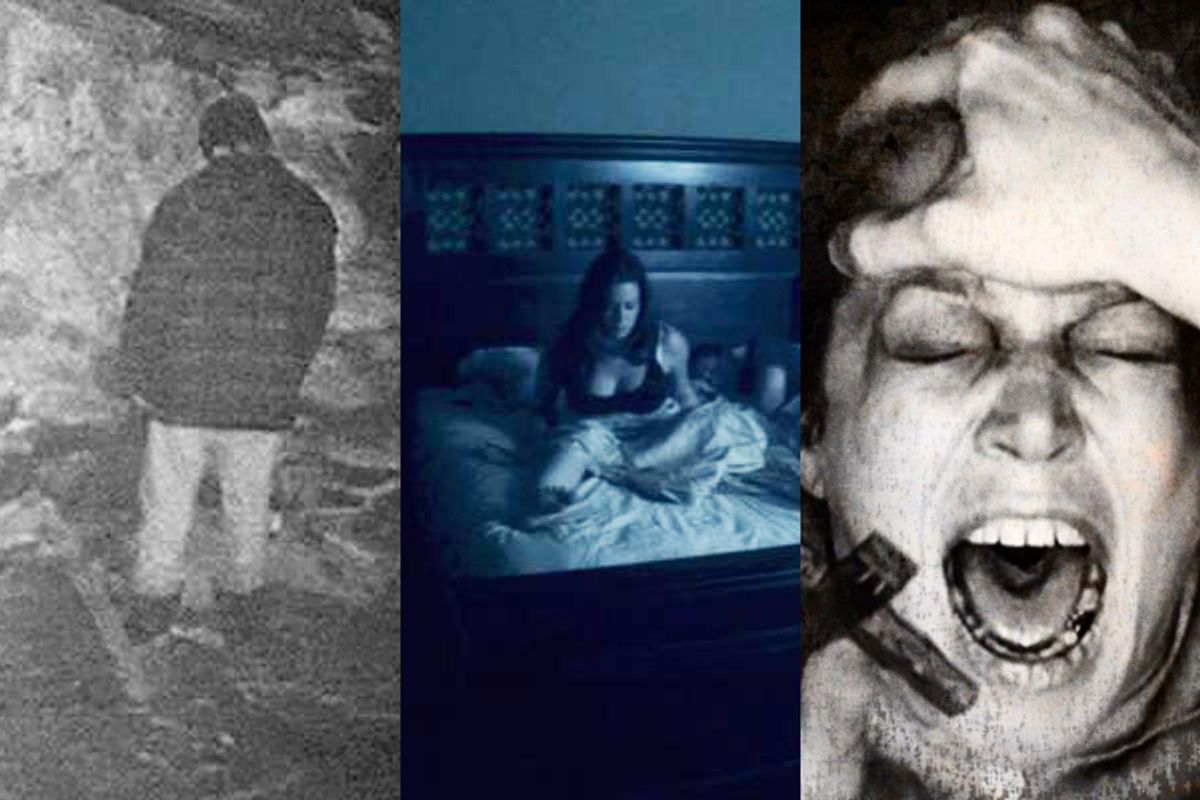

It's a very profitable way to make a movie, so the past half-decade has seen an outbreak of similarly faked “found footage films,” fictional narratives that tell their stories through scenes shot by the characters, later “unearthed” to explain the horrifying monster invasion/zombie attack/ghost haunting. The top-10 in this genre have grossed a total of $607 million in the U.S. alone; the low-fi aesthetic not only encouraged but expected by audiences means that these films can be produced for a fraction of their eventual gross. The most successful have been the Paranormal Activity films, tense ghost stories composed of staged home movies and surveillance video. The third installment of the franchise opened last fall to a gross of $52.5 million — the biggest opening weekend for an October release in movie history.

For moviegoers, the films speak in a faux-documentary visual language that has become commonplace, as the 12 years since "Blair Witch’s" theatrical release have corresponded with the all-but-unstoppable rise of reality television and advances in both portable filmmaking technology and home video streaming. Since the early days of the “direct cinema” movement, documentary filmmakers have relied on low-budget tools (hand-held 16mm cameras, early and primitive video equipment, portable sound recorders) to tell their stories. Now, television swipes the tropes of fact-based documentary filmmaking (hand-held camera, overheard conversations, talking head interviews) and twists (some would say corrupts) them into a manufactured “reality,” while the kind of quality high-definition images that doc filmmakers would’ve given their eye-teeth for less than a decade ago are tossed on consumer still cameras and even smartphones, almost as an afterthought. Those images don’t just end up in the homemade conspiratorial rants and gruesome war videos we see on YouTube; they’re in the documentary films at the local art house, the investigative films on cable, the reality shows in prime time. And they’re in the genre films at the multiplex, which reflect how we’ve ingrained in our collective subconscious the idea that truth doesn’t always come in a slick, handsomely produced package.

But as Alex Juhasz notes, “There’s always been an interest in fake found-footage films. It’s not new to our time.” A professor of media studies at Pitzer College in Los Angeles, Juhasz co-edited the book "F Is for Phony: Fake Documentary and Truth’s Undoing." Juhasz points out examples within the work of Orson Welles, from his 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast (a kind of radio cousin to the found footage film) to the “News on the March” newsreel in "Citizen Kane" to his documentary on the very subject of fakery, "F for Fake." The scenes of a fictional documentary crew’s murder in the notorious 1980 Italian horror film Cannibal Holocaust were so convincingly staged that director Ruggero Deodato was charged with murder, and had to produce his actors for Italian courts. There is the “mockumentary” tradition, normally employed for comedic effect (as in the films of Christopher Guest) but occasionally used for dramatic purposes (see "Laws of Gravity," "Man Bites Dog" and "Husbands and Wives").

So if it’s not “new,” perhaps the found footage film falls into the tradition of cinematic styles like Kino-Pravda, neorealism, cinéma vérité, and Dogme ’95 — all of which have, in varying ways, challenged and scrambled our engagement with cinematic reality. And this is where real questions of representation and perception come into play. The slickness of a film’s cinematography, the discipline of its camerawork, the transparency with which it has been blocked, rehearsed, and placed in front of a camera: does the absence of these common elements trigger some sort of reactive response? If we see a hand-held digital/cellphone camera stumbling upon a shrieking ghost, does it (consciously or not) somehow seem more “real” than if the same ghost were shot by a 35mm Panavision camera mounted on a Steadicam?

New York University cinema studies professor Dan Streible hosts a biannual symposium of home movies, amateur films and other ephemera. “Our perception of what we see as ‘real’ in a two-dimensional moving image is determined as much by convention and expectation as it is by our genuine ability to distinguish photographic reality from the visual reality in front of our eyeballs,” he says. In other words, old conventions are replaced with new ones. In the 1960s, cinéma vérité introduced hand-held camerawork, clunky zooms, catch-as-catch-can sound recording. Those elements have been part of our visual language for so long now that they trigger an immediate response in a viewer, whether they realize it or not. “It’s coded as documentary,” Streible explains, “and even if the viewer immediately knows that it’s not real documentary, they at least are in that nonfictional realm of perception, and so they might be willing to give it more credibility.”

But that idea of credibility is where the notion of the found footage film starts to get complicated. The entire premise of these movies is that what we’re seeing is real, not staged, and it is often painstakingly presented as such, though it’s hard to imagine who is genuinely fooled anymore. The first "Paranormal Activity" begins with a solemn on-screen note that “Paramount Pictures would like to thank the families of Micah Sloat & Katie Featherstone [the main characters] and the San Diego Police Department”; the end credits flash on-screen for less than five seconds, buried after a full minute of black screen. But even those who might have bought the artifice the first time around would have to wonder, by the third film in the franchise, exactly how one family created so many spooky home movies — particularly after the most recent installment, comprising much “older” material from the protagonists' childhood, shot with a VHS camera in the mid-1980s that somehow captured HD widescreen images.

“It used to be that everyone who wrote about cinema talked about these references to realism, and photography’s direct relationship to physical reality,” Streible says, but we're now immersed in a digital reality. “The capture now is so entirely manipulatable, pixel by pixel, that there’s no guaranteed veracity that the image you see bears a direct relationship to the real. You’re basically trusting the source that puts it before you. So it creates a kind of skepticism.” Does the conscious effort to leave in the rough edges, to frame a film as something that could have come off your own camera, or laptop, or cellphone, seek to somehow neutralize that skepticism?

Perhaps, but there’s little evidence that it’s working. As the industry gets more digitized (and the recent reports that Panavision and ARRI are ceasing production of celluloid film cameras is another strong indication of that shift), our trust in what we see on-screen will presumably continue its decline. “There’s not even a camera necessary,” Streible notes. “We can computer-generate all imagery, whether it’s documentary imagery or completely rendered from someone’s imagination. So in that sense, all films, regardless of anything, can be seen as animation, subsets of animation … It’s an important concept for people to start accepting, especially for commercial films that we’re going to see and pay for, it’s all going to be generated off of pixels.”

So if the audience knows that what they're seeing is no more “real” than a "Saw" movie, or a sci-fi epic, or the latest Adam Sandler comedy, the filmmakers’ motivation for bothering with the pageantry of the shaky camera, the night-vision cinematography, and the mock digital “hits” seems unclear. But Juhasz suggests that, in some strange way, it could be precisely because we’re not sure we believe in the premise. “My current belief is to suggest that that form is relatively defanged,” she says. “If you look at those movies that you’ve mentioned, you can say it’s actually a way of perceiving the world that we’re quite comfortable with at this point — where we’re not certain.”

So it almost becomes a postmodern moviegoing experience, an intellectual exercise — the viewer is engaged on a different level, beyond the artificial emotional responses that a horror film (or a tragedy, or a romance) attempts to manipulate. Instead of the right brain disconnecting as the left brain experiences fear, sorrow, or joy, the right brain is asking questions. “Is this true, is this history, did this happen, is it faked, is it about faking, when am I supposed to notice that it’s fake? That’s a question that’s very live and common for us in 2011,” Juhasz says. “We live in a time where all of us are so aware of how technology manipulates the truth, because we do it ourselves, that that skepticism is not uncommon — that skepticism is the dominant mode. It’s not the radical mode, it’s the dominant mode.”

This hasn’t always been so. When the current vogue of found-footage cinema began with "Blair Witch," there were people who believed the events really happened. But that was 1999, when reality TV was still confined to MTV’s "The Real World," when a Hi8 video camera would set you back $500, and online video was still confined to cumbersome QuickTime downloads.

No other modern found footage film has had "Blair Witch’s" impact. Yet the trend continues, perhaps because they’re so cheap to make, perhaps because the form builds a framework of evidence and identification and “reality” around the extraordinary and often supernatural events common to the horror genre (ghosts, alien attacks, zombie uprisings), perhaps because even if moviegoers aren’t going to be fooled in a post-"Blair Witch" world, they at least appreciate a filmmaker’s efforts to pull one over on them.

And sometimes, simply enough, the films are scary. “Like any new movie trend,” says film critic Scott Weinberg, writer/editor for Fandango, Twitch and the horror site Fear.net, “it will be abused and exploited by a wide variety of short-minded or uninspired filmmakers, but I've seen a large number of legitimately entertaining found-footage horror films from all around the globe. Used in moderation, I believe it's a fantastic storytelling device, and one that lends itself particularly well to the horror genre.” As Juhasz notes, the more media-savvy members of the audience usually see through these low-budget horror flicks — and at this point in time, more members of that audience are media-savvy than ever before. “We really, as a society, are extremely afraid, delighted, curious, all of these things, about the loss of evidentiary truth,” she says. “And those movies tap into that.”

Shares