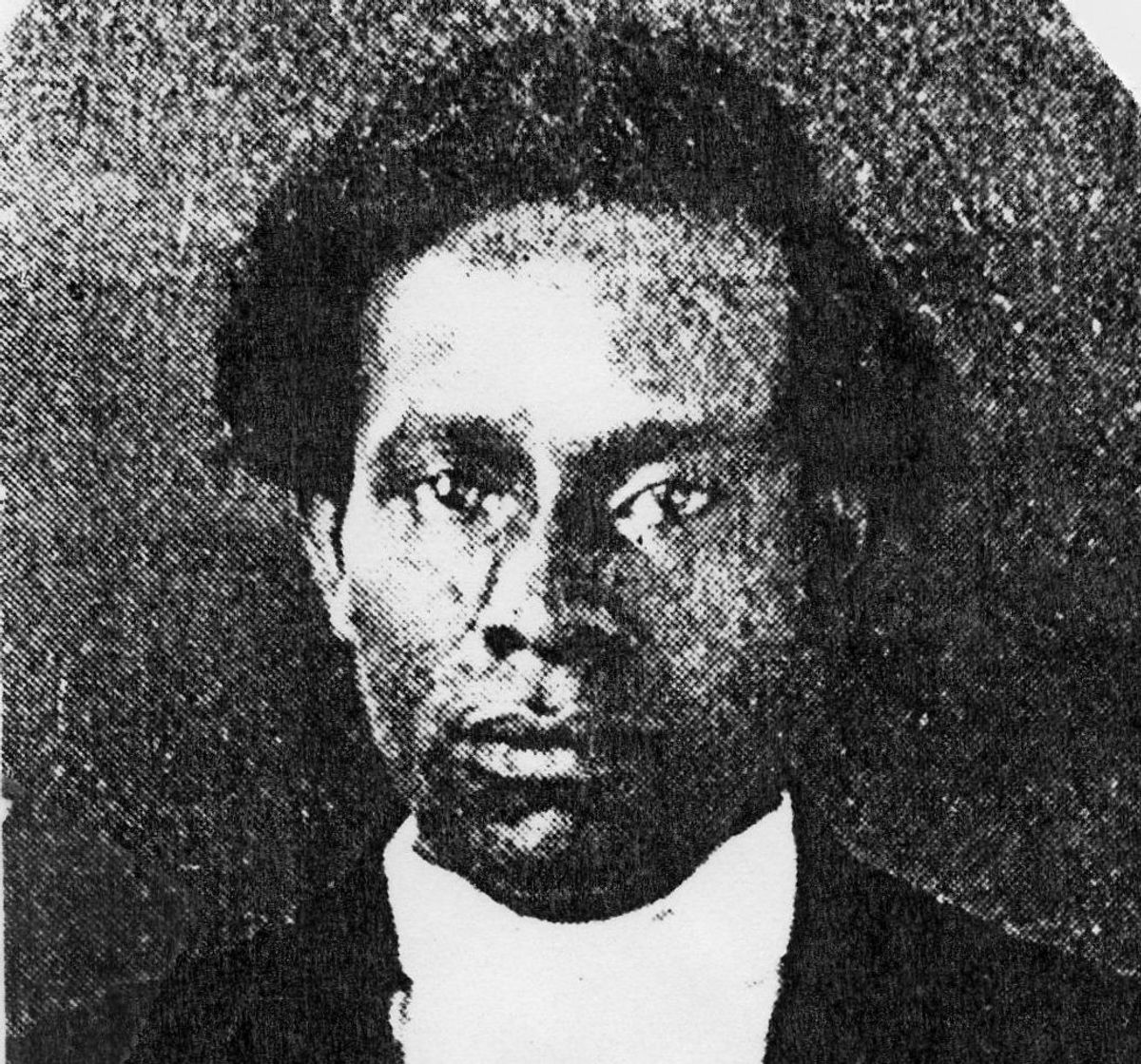

Before there was Martin Luther King, there was John Francis Cook. He was Washington's first civil rights leader, a preacher, and teacher who founded of the 15th Street Presbyterian Church, which originally stood in the place now known McPherson Square, today the home of the OccupyDC camp.

And just as some once hoped to rid the capital of Cook, so some wish to get rid of his spiritual descendants camped on 15th Street. Rep. Right-wing bloggers revile them. Darrell Issa, chairman of the House committee with responsibility for the District, calls them "lawbreakers," and wants them evicted. Mayor Vincent Gray wants them removed because they are allegedly unsanitary, a charge the occupiers reject.

Things change perhaps less than we think. When John Cook first held forth on 15th Street in the 1830s and 1840s Washington was the capital of a slaveholding republic dominated by congressmen who (like their political descendants today) defended an extreme version of property rights. Cook not only denounced the 1% of the day--those who insisted on the white man's right to own property in people. He also taught young people not to accept the injustices inherent in the status quo. He too was reviled.

Cook lived and worked in the neighborhood of what would become McPherson Square. Born into slavery in Fredericksburg, Virginia, he came to capital in 1826 when his aunt, Lethe Tanner, a free woman of color who ran a vegetable stand near the White House, bought his freedom. At eighteen years of age, he enrolled in John Prout's school for black children near the corner of Fourteenth and H streets. As he learned to read and write, his capacious intelligence became evident to all. Before long, he obtained a job in the government's Land Office on Seventh Street where his "indefatigable application" to learning was "a matter of astonishment" to the white man who hired him. When Prout had to leave town for aiding a runaway slave, Cook quit his government job and took over as the school's headmaster.

From the start Cook exhibited a lifelong impulse to reform society and improve his fellow citizens. In 1834, he organized what he called the Philomathean Talking Society, which was kind of a General Assembly for young black men. He encouraged free discussion of the issues of the day, advocated temperance, and handed out copies of forbidden anti-slavery publications from the newly-formed American Antislavery Society. Cook was a community organizer just slightly ahead of his time.

In 1835 he traveled to Philadelphia where he served as the Secretary of the 5th Annual Negro Convention in Philadelphia, a gathering of free men of color from all over the country. Cook helped write the convention's stirring declaration of war on slavery.

“We rejoice that we are thrown into a revolution where the contest is not for landed territory but for freedom. . . . Let no man remove from his native country, for our principles are drawn from the book of Divine Revelation, and are incorporated in the Declaration of Independence, ‘that all men are born equal.’”

Cook insisted on American justice with the same biblical cadences that King would master in the 20th century:

“We pray God . . . that our visages may be so many Bibles that shall warn this guilty nation of her injustice and cruelty to the descendants of Africa, until righteousness, justice, and truth shall rise in their might and majesty, and proclaim from the halls of legislation that the chains of the bondsman have fallen—that the soil is sacred to liberty, and that, without distinction of nation or complexion, she disseminates alike her blessings of freedom to all mankind.”

Then, as now, Washington was the site of national political struggle. In the summer of 1835, the American Antislavery Society—like the Occupy movement today-- injected new ideas and idealism into American politics. Like the 21st century occupiers using social media, the so-called abolitionists adopted a new technology—steam-driven printing presses—to bypass the traditional newspapers and send their message directly to the American people. In what was probably the first direct mail campaign in American politics, the society started sending its publications, featuring stories and drawings of slavery's many injustices, to every leading white man in the city.

Then as now, many didn't care to be confronted with the realities of the country's economic order. In August 1835, mobs of poor white men started attacking the city's free people of color, especially those active in the abolitionist cause. The city's leaders stood aside or cowered in fear. Cook's school was trashed, and he had to flee on horseback to Pennsylvania. No one was killed in the white riot of 1835 but the abolitionists, black and white, were driven from the city, at least temporarily.

This is not to suggest that those who want to evict OccupyDC today are the equivalent of a lynch mob—they are not. Rather, the point is that radical ideas of equality will always make powerful people and their allies uncomfortable. Some times it is easier to chase a man away than to respond to his demands. (The decision of whether the occupiers stay or go belongs to the National Park Service, which has responsibility for maintaining McPherson Square.)

But Cook demonstrated how hard it is to get rid of an idea. A year after he was forced to leave town, he returned to Washington and resumed teaching. He founded 15th Street Presbyterian in 1838 and served as the pastor for the next 17 years. He almost single-handedly kept the anti-slavery cause alive in the nation's capital, while educating couple of generations of African-American children along the way. His two sons would become professors and help found Howard University after the Civil War. When Cook died in March 1855, one newspaper reported that his funeral was attended by “clergymen of no less than five denominations, many of the oldest and most respectable citizens, and a vast concourse of all classes, white and colored.” Seven years later, in April 1862, slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia. The political power of the slaveholding 1% percent was dismantled, and the dream of the abolitionists, once scorned by the press and the pundits, had became the law of the land.

Today, John Francis Cook is remembered in Washington mostly at his church. An elementary school named in his honor has been closed. Few, if any, of the DC occupiers know his story. But the ideals of equality he first planted in the vicinity of McPherson Square are growing there again. Like Cook, they may be forced out. Like Cook, they are sure to return.

Shares