Words have been important to me for as long as I can remember. Their sound, their construction, their origins. Because of that interest, there are few places I could have been raised that would have provided more wonderful raw material than the southeast quarter of North America.

The word Tennessee means “land of trees” to the folks native to that part of the world three or four hundred years ago. Residents of the region respected the land and their attention to the details of their surroundings stands out in their descriptions. They examined their environment thoroughly, creating drawings of what they saw from a mountain that provided an unobstructed view for miles in all directions. South and east of the mountain, a blanket of treetops led to trails marked by the Seminoles. Due west, the Chickasaw people lived on the banks of the horseshoe-shaped Tennessee River that one encountered twice as it sliced the state into thirds. And everywhere stood dense forests. Tennessee, they say, was once 90 percent trees, the land of trees.

The natives from the heights of the Appalachians scattered when the new folks came into the mountains from the east. These graceless, grimy intruders were more than a different tribe. And less. They were more than a different skin color and language. They had no respect for the land and its inhabitants. Arriving in waves, they attacked the mountains as if to level them. They slashed jagged holes and dammed the streams before thunderous explosions collapsed the face of hillsides, leaving only the ugly scars to evidence their search for the black rocks they called coal. The natives charted their ragged trails of mutilation from the peak above Chattanooga. And they led their families west.

When I was a boy in Tennessee, our first class in the morning was geography and time was always dedicated to Tennessee and how it was connected to history. Tennessee was the Volunteer State. University of Tennessee sports teams were the Volunteers. I remember being shown pictures of Davy Crockett and Smoky the Bear. I also recall the slightly curved diagonal line I drew that linked Knoxville to Nashville to the city named after an ancient Egyptian metropolis, Memphis.

Memphis, Tenn., was only 90 miles west of Jackson, my home. But Memphis was as far away as the North Pole in my mind. People in Jackson were always talking about somewhere else, mostly Memphis, because it was a close somewhere else and you could drink alcohol there, while Jackson was in a dry county. I talked about going to Chicago, where my mother lived. Some of my grandfather’s relatives were in Memphis and I had visited them, but what I remember about the trip was getting carsick and throwing up.

The history that we were given about Memphis was done in light pencil that hopscotched its way to a semisolid landing with Elvis Presley on "The Ed Sullivan Show." The city had started as a midway market, a meeting place on the banks of the Mississippi River that squatted in the muck almost squarely between New Orleans and Chicago. As such, it provided a perfect location for traders of all description and from all directions, who brought everything to exchange — from furs to furniture and cotton to cattle. As the steamboats and paddle wheelers sought the shallows of Memphis and St. Louis, they stirred great clouds of silt and sand, turning the surface of the waterway a burnished brown. The Mississippi became known as the Big Muddy.

The docks at the edge of the village were a magnet for hunters, trappers, farmers, and natives, who rolled up in wooden wagons to trade loads of tobacco, produce, and buffalo hides for guns, whiskey, and farm implements. They all walked and rolled past the narrow, squalid shacks, no more than cages, where there were echoes of moans and rattling chains from human cargo.

The Memphis day was from “can see” to “can’t see,” and with the first hint of another sunrise the procession from the docks to the foul smelling mud huts beneath the auction blocks began. There, nearly naked black men and women barely covered by rotting rags were led in, bound and shackled, with rawhide nooses around their necks. The least cooperative captives were hobbled with ankle chains that limited them to short, stuttering steps. They would be sold, these bucks, to the cutthroat Cajuns from the sea-level swamps. It was said that each year spent in the paralyzing heat of a Louisiana summer took five years off a man’s life. When a slave was sold to the Lords of Louisiana, the observers lamented that he’d been “sold down the river.”

Memphis matured from midway market to a major metropolis. Saloons and whorehouse tents, once soaked with the sweat of drunken sailors and reeking with the acid stench of swine, slime, sewage, and slaves is now better known for Graceland and the Grizzlies than for Beale Street and the blues. Its filthy foundation as a headquarters for whores and for humans sold to the highest bidder was obscured by the magic of musical melding. Sun Records considered itself the fuse that lit the 1950s with Elvis and rock ’n’ roll. With Carla and Rufus Thomas and Otis Redding, Stax Records brought blues to the hit parade with hooks and horns and a solid beat, evolving into Al Green and Willie Mitchell. Memphis meant music.

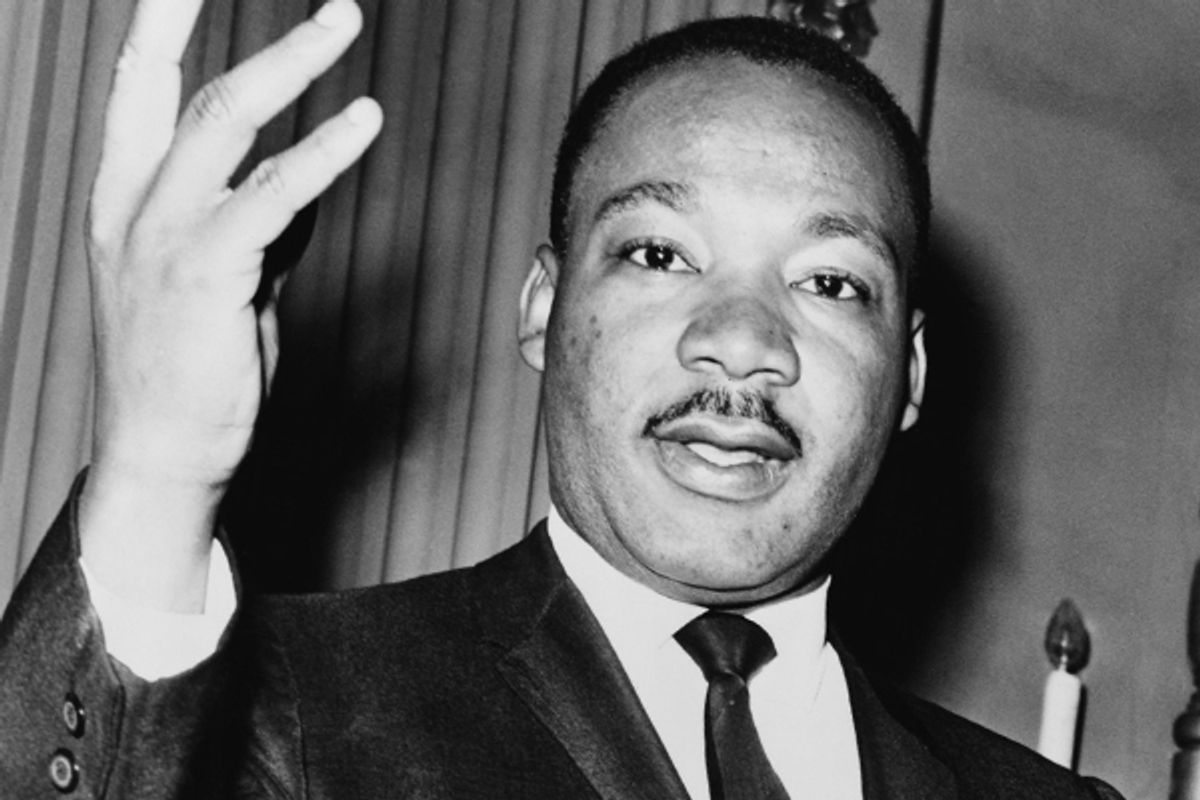

And unless you stop to think for a minute, you might forget that it was in Memphis that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot and killed on a motel balcony on April 4, 1968. That assassination is one of our starting points.

Stevie Wonder did not forget.

In 1980, Stevie joined with the members of the Black Caucus in the United States Congress to speak out for the need to honor the day Dr. King was born, to make his birthday a national holiday.

The campaign began in earnest on Halloween of 1980 in Houston, Texas, with Stevie’s national tour supporting a new LP called "Hotter Than July," featuring the song “Happy Birthday,” which advocated a holiday for Dr. King. I arrived in Houston in the early afternoon to join the tour as the opening act. I was invited to do the first eight shows, covering two weeks, and I felt good about being there, about seeing Stevie and his crazy brother Calvin again.

Somehow it seems that Stevie’s effort as the leader of this campaign has been forgotten. But it is something that we should all remember. Just as surely as we should remember April 4, 1968, we should celebrate January 15.

And we should not forget that Stevie remembered.

*

January 15, 1981

I would never claim to be the smartest son of a gun on the planet. If I had claimed that, all of you readers would know by now that I was lying. But by the same token, by then I had been in this business for 10 years and had to feel as though I knew more than when I started. And also, by then, I had been working on the "Hotter Than July" tour for 10 weeks, and had some new information crossing my mind as I climbed the back stairs onto the temporary stage and looked out at perhaps fifty thousand people standing shoulder-to-shoulder across the expanse of the Mall chanting, “Martin Luther King Day, we took a holiday!”

As of January 15, I could look back 10 weeks to Halloween since I’d been working on the "Hotter Than July" tour. It was a project that, when taken as a whole, was set up to cover 16 weeks, or four months, a third of a year. The endeavor was cut into two six-week halves with a break, a rest period, that lasted a month. Since the tour had gone on break from the West Coast in mid-December, my life had not been free of upset and disruption, but business-wise and music-wise things were on schedule. My new album, called "Real Eyes," had been released around the first of December; some support for our performances over the next two months or so could be expected. That meant everyone would get paid and some of the music I was writing and arranging for our virtually new configuration with the horn section was starting to fit. That was good.

In essence, this rally was the halftime show before the second six-week half. But if you’ve ever seen the Florida A&M marching band, just how long do you think it takes to perfect those steps, formations, baton tosses, improvisations, and instrument playing?

So nobody that I could see up there seemed likely to jump up and start majoretting up and down Constitution Avenue, but I was pleased to see how many people thought Stevie was worth supporting.

One thing that knocked me out looking at this halftime show was how much I had not thought about. Like how much work was involved in organizing a fucking rally. That was what Stevie had done and what had to have taken up so much of his offstage time when we were playing and what must have consumed what I was calling a “rest period,” the month off between December 15 and today, Dr. King’s birthday. This had to have dominated a great deal of his time and probably much more of his thoughts. The rally. Ways to publicize it, ways to dramatize it, ways to legitimize it.

Some of it was obvious. You had to have permits, like a license to have a parade. That seemed bizarre, but it took a necessary number of police to close certain streets or divert traffic or just stand around looking like police. And on the monument grounds there were wooden saw horses and security and crowd restraints and a stage and sound equipment and technicians to set it all up and run it. And I was enjoying another piece of equipment I felt was necessary: a heat-blowing machine to warm my chilly backside.

My respect for Stevie Wonder expanded in every direction that day. I was following his lead like a member of his band, because seeing as he had envisioned was a new level of believing. It was something that seeped in softly, and when you were personally touched by someone’s effort and genuine sincerity, your brain said you didn’t yet understand but your soul said you should trust.

We had been to Mayor Marion Barry’s office earlier in the day. There I was introduced to the winner of a citywide essay contest that had run in the D.C. school system. The theme of the essay was why Dr. King’s birthday should be a national holiday, and the contest was open to middle and high school students. A seventh grader won, and I thought the fact that he was in the seventh grade was the headline out of that. After they introduced us, I took a few minutes to read his essay so I would know what to be listening for — my cue when he came to the end, because now, at the rally, I would present him to the crowd.

It was a gray winter day, the type of gray that looked permanent, not bothered with clouds or memories of blue. Gray, sullen, not threatening but sporting an attitude. Somebody was organizing things, checking out how many speakers were on hand who wanted to say a few words.

When we got to the part of the program where the kid was to read his essay, I introduced him and walked back offstage. I kept one ear on the loudspeakers because I had to be on it when he was through. That would be no more than five minutes, max.

At some stage, I heard the kid having trouble reading his own essay. I thought he might have been nervous with the big crowd and the TV audience, it must have felt like everybody in the world was watching him. I could hear the crowd getting restless and a couple of folks started giving the kid a hard time. Suddenly, mid-sentence, or maybe in the middle of a word, the kid stopped. He turned around and went back to his seat. It was a seat of honor, right behind the podium in the middle of the stage.

It was quiet now, just a sprinkle of sympathetic applause. I found my list of speakers and introduced the next one, but I realized something had gone wrong. As the next speaker approached the podium, I went over to the kid and said, “Let me see that essay there, brotherman.”

And sure enough, he had stopped at the top of his second page, a good five or six paragraphs from the end. He had been reading from a mimeographed copy of his essay, and the ink was faded — I would have needed night goggles or some shit to see what was on that paper.

I waited until that next speaker was through, then went up there and explained to the audience that I was going to introduce the kid again, and that he was going to read his essay to the end, and that they were going to listen. Yeah, I knew it was cold, I said, but it was cold for this kid, too, and he was reading from a faded copy, and I didn’t want to hear nothing from the crowd but applause, period. “Have some patience with the young brother, please.”

After I introduced him, I walked backstage again. He started to read again, and I heard him coming to the point where he had faltered, the part on the page that was damn near invisible. He started to falter again, and I listened for some wiseass to say something. But then it started to go smoothly, and I looked over and there was Diana Ross standing next to him with her arm around his shoulder. Without being in the way, without making it her essay, she helped him over those rough spots. My man’s confidence got a lift and the crowd started to appreciate what he had written. I stood there thinking, There must be thirty or forty adults up here on this stage, and she’s the only one of us who thought to go up there and help the brother!

Jesse Jackson spoke, too. His attitude was about changing the laws and about people needing to know more about Thurgood Marshall and needing to know more about what happened, because the way to change America was through the law. You see, if you don’t change the law, you don’t change anything. You could burn your community down and somebody else would build it up; all you were doing was burning down some houses. But if you changed the law, then you had done a whole lot to change the foundation of society.

To be sure, I looked at the appearances there and then as a tribute of respect for Dr. King. But they were also an indication of respect to a brother for taking a step to bring a positive idea forward, to remind some of us that we could hardly criticize congressmen and other representatives for inaction if their attempts to push ideas important to us out in the open received no visible interest from those it purportedly would benefit most.

Yeah, this piece of legislation to make Dr. King’s birthday into a national holiday looked like a long shot, especially being raised at the same time America was electing Ronald Reagan, who would be inaugurated at the other end of the Mall in five days. But if our community was to make valuable contributions, then those who made them had to be recognized as offering something of value. Why would the next one of us feel that he or she should make the effort, marshal the strength, and somehow fortify him or herself against the opposition that always seemed stronger, longer, with more bonified, bona fide other side, if even a man who won the Nobel Peace Prize was ignored where those efforts for peace had done the most good?

Something was wrong with ignoring a man here that the world had acknowledged everywhere. To bring about a change inside the minds of people is difficult. That’s why there are books and teachers and laws. A change in people’s hearts is even more difficult to gauge. There has to be some sign from those who represent them in a society where folks live together without touching. There has to be some assurance that they have learned that people who showed the world did not present offerings that only people outside our country needed. Certainly recognition of a Desmond Tutu or a Martin Luther King by panels of objective individuals pointed out the value of those they honored beyond the constrictions of geography; that the work they did, in essence, came from this or that community but was of value to all mankind. How could this country purport to lead mankind and ignore what mankind needed and respected? Any American, raised in the atmosphere of abuse and violence, who suggested that centuries of deliberate discrimination could be overcome without responding to the oppressors in kind was not just valuable, but invaluable.

This was what Dr. King signified and this was what Stevie Wonder was calling on America to honor. All holidays should not be set aside for generals. To have the country honor men for doing what they did in a time when difficult personal decisions made their actions worthwhile for the overall good meant the same thing for all citizens.

That had been both the point and the ultimate disappointment of what had once been called “the Civil Rights movement.” What was special about the 1960s was that there was only one thing happening, one movement. And that was the Civil Rights movement. There were different organizations coming from different angles because of geography, but in essence everybody had the same objective. It came so suddenly from so many different angles, things happening in so many different towns and cities at once, that the “powers that be” were caught off guard.

The powers had taken control when Eisenhower was elected. He held office while they secured a grip around our throats. He even spoke about it before he left office. But there was an oversight. They overlooked the same folks that they always overlooked. See, this was not long after Ralph Ellison had summed us up in "Invisible Man." We were the last item on the last page of the last program. But that didn’t last. Because the last thing they had counted on was active dissent. Until the 1960s “the movement” had been the exclusive property of middle aged and old people. Then it became a young people thing, and as the 1960s opened up, the key word became “activism,” with Stokely Carmichael and the SNCC, “Freedom Rides,” and sit-ins. There was a new feeling of power in Black communities. And once it got started, it was on the powers like paint.

But at some point a difference was created between “equality,” “freedom” and “civil rights.” Those differences were played up because something had to be done about the sudden unity among Black folks all over the country. Folks got more media attention whenever they accentuated the differences. There were media-created splinters. Otherwise the Civil Rights movement would have been enough, and would have been more successful. Accomplishing the aims of the movement would have made “gay rights” and “women’s rights” and “lefts and rights” extraneous. But divide and conquer was the aim of programs like COINTELPRO. And even though it ended up working damn near backward, it worked.

They separated the fingers on the hand and gave each group a different demand; we lost our way. Separated, none of us seemed to know to watch out for COINTELPRO. J. Edgar Hoover was dead, but in D.C. they honored what he had said.

There I was at the halftime show, looking up and down the field, and I could see for the first time. I could see what this brother had seen long before, what really needed to be done.

We all took the stage.

The crowd continued to chant, “Martin Luther King Day, we took a holiday!”

Stevie stepped up to the mic and addressed them:

“It’s fitting,” he said, “that we should gather here, for it was here that Martin Luther King inspired the entire nation and the world with his stirring words, his great vision both challenging and inspiring us with his great dream. People have asked, ‘Why Stevie Wonder, as an artist?’ Why should I be involved in this great cause? I’m Stevie Wonder the artist, yes, but I’m Steveland Morris, a man, a citizen of this country, and a human being. As an artist, my purpose is to communicate the message that can better improve the lives of all of us. I’d like to ask all of you just for one moment, if you will, to be silent and just to think and hear in your mind the voice of our Dr. Martin Luther King ...”

Excerpted from "The Last Holiday" by Gil Scott-Heron. Copyright 2012 by Gil Scott-Heron. Published by Grove Atlantic Books.

Shares