Everything about Newt Gingrich screams "general election disaster." He is burdened with far too much personal and ethical baggage, is far too prone to needlessly inflammatory and polarizing antics, and turns off far too many voters with his arrogance and unconcealed contempt for his opponents.

The three most recent national polls all show his unfavorable rating at or near 60 percent -- more than double his favorable score. This mirrors what happened the last time Gingrich played such a prominent role on the national stage, when he claimed the House speakership after the 1994 election and promptly established himself as the country's most despised public figure -- the star of an estimated 75,000 Democratic attack ads in the 1996 campaign cycle. The more most people see of him, the less they like him.

So while it's theoretically possible that Gingrich would somehow defy his reputation and overcome his worst tendencies in a fall campaign, George Will was probably on solid ground when he said in the wake of Gingrich's South Carolina triumph: "All across the country this morning people are waking up who are running for office as Republicans, from dog catcher to the Senate, and they’re saying, ‘Good God, Newt Gingrich might be at the top of this ticket.'’’

The good news for Will, who recently wrote that Gingrich "embodies the vanity and rapacity that make modern Washington repulsive," and other worried Republicans is that the former speaker's breakthrough isn't exactly unprecedented. Candidates widely seen as unelectable by their party's elites have emerged during past primary seasons as threats to win the nomination, and the elites have generally managed to stop them. The question is whether they're still capable of doing it in 2012 -- or if the tricks they've mastered in the past few decades simply don't work anymore.

After all, there was a period when both parties' elites lost control over their presidential nominating processes.

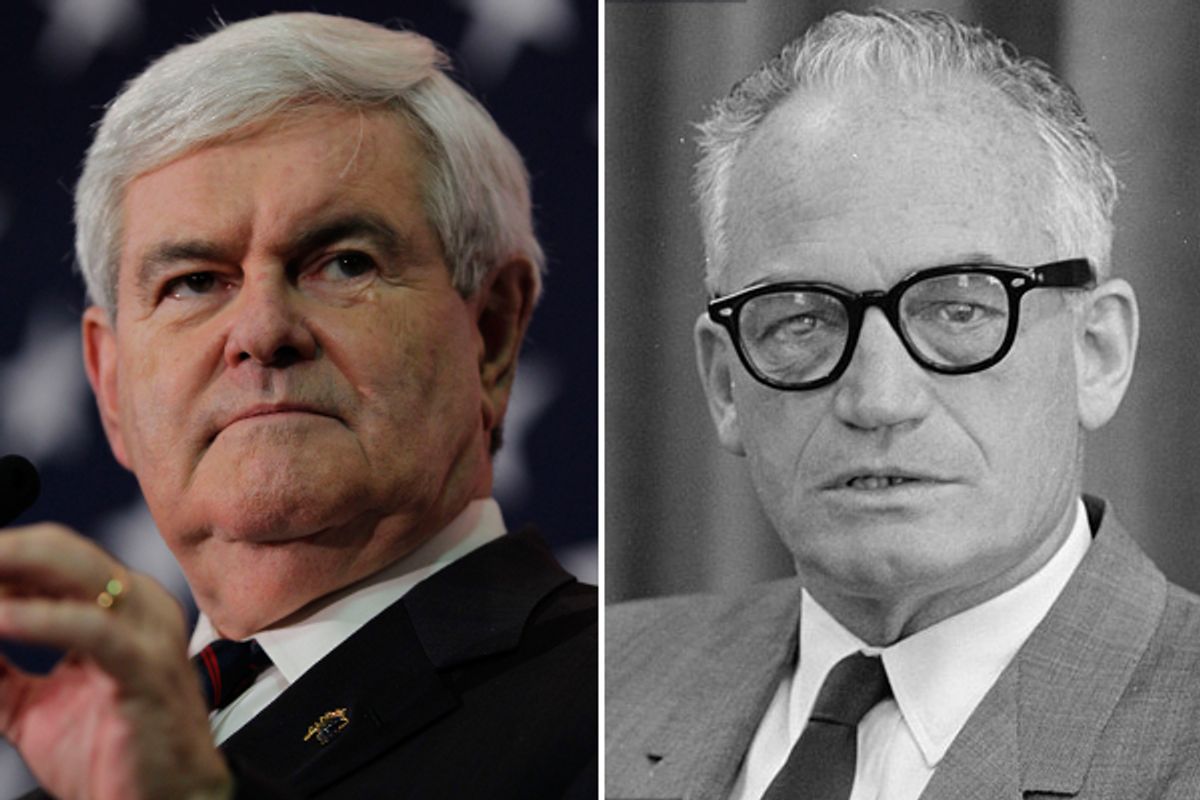

This was how the GOP ended up nominating Barry Goldwater in 1964. At the time, the party was still dominated by a moderate Northeast sensibility, but movement conservatives were steadily growing in force at the grass-roots level. While the establishment wing dawdled and failed to produce a consensus primary season candidate, conservatives rallied around Goldwater and wired low-visibility caucuses and state conventions for him, gobbling up delegates with virtually no one noticing. That and several statement-making primary victories over Nelson Rockefeller (the establishment wing's scandal-plagued stand-in) made Goldwater unstoppable at the convention. GOP elites were left to watch in horror as Goldwater, whose far-right views and vote against the 1964 Civil Rights Act made him unacceptable in vast swaths of the country, lost by nearly 23 points to Lyndon Johnson.

Democrats had a similar experience in 1972, when George McGovern took advantage of new party nominating rules that he helped write, which placed more emphasis on state primaries and caucuses. This was the year the Iowa caucuses were born, and McGovern became the first candidate to receive a bounce from a "better than expected" showing in them. The same thing happened in New Hampshire, giving the insurgent South Dakotan momentum that lasted through the spring primary season, from which he emerged with just enough delegates to secure the nomination. But his antiwar politics and army of young, culturally liberal backers alienated the party's old guard and gave the Nixon campaign ample ammunition for the fall, leading to an epic landslide.

Four years later, when the number of primaries expanded further, Democratic elites were again caught flat-footed, this time by Jimmy Carter, whose nomination they found themselves powerless to stop. But Carter, at least, proved electable in November -- even if his presidency was marked by hostility to organized labor and other traditional components of the party's base, producing a Democratic civil war that culminated in Ted Kennedy's 1980 primary challenge to Carter.

But Carter's triumph marked the last time the elites of either party were saddled with an unwanted nominee. Since then, the basic rules have remained the same for Democrats and Republicans, with primaries and caucuses -- and not brokered conventions -- deciding nominations. While this would seem to take power away from the elites, they've exercised control by using their outsize influence to shape mass opinion within the party, uniting to promote candidates they deem acceptable and to discourage the nomination of those they consider unelectable.

So, for instance, when Jesse Jackson scored a stunning victory in the Michigan caucuses in March 1988 and took the delegate lead, Democratic elites -- elected officials, commentators, interest group leaders, fundraisers and activists -- used their platforms to send a clear signal to Democratic voters in subsequent battlegrounds: Don't do it. Jackson then suffered momentum-killing losses in Wisconsin and New York and never came close to winning a primary again. The same thing happened to Jerry Brown when he upset Bill Clinton in the March 1992 Connecticut primary, a result that briefly threatened Clinton's hold on the Democratic nomination. But "Governor Moonbeam" frightened party elites, who helped push Clinton to a victory in New York two weeks later, and from then on Brown was a non-factor.

Republicans had their own experience with this in 1996, when Pat Buchanan pulled off a victory in the New Hampshire primary. The result: Virtually every player in Republican politics united behind Bob Dole, who crushed Buchanan in the next contest (South Carolina) and never looked back. In fact, we've seen the power of GOP elites in the current campaign. Think back to December, when Gingrich suddenly opened massive leads in national and key early state polling. At that point, a host of panicked party opinion-shapers raised their voices in an effort to snap the party base out of its infatuation. And it seemed to work. By Christmas, Gingrich's poll numbers had fallen to earth everywhere.

But as his South Carolina landslide showed, they couldn't keep him down.

Complacency may be the explanation for this. Gingrich's polling slide culminated in a distant fourth place finish in Iowa and an even worse showing in New Hampshire. So it may just be that the elites thought their work was done and let up on the gas, leaving Gingrich with a chance to sneak up on them in South Carolina. If that's the case, then they should be able to contain his new momentum by turning the heat back up to its mid-December level.

The other possibility, though, is that Gingrich has neutralized the intraparty attacks -- that the elites succeeded in planting doubts about him, but that the party's base has now decided that they'd rather have Gingrich than Romney. This would be consistent with the phenomenon that defined the 2010 midterm campaign, when Tea Party-friendly Republicans ignored pleas from party elites and nominated "pure" candidates with profound general election liabilities in several key races -- think Sharron Angle, Christine O'Donnell, Rick Scott, Ken Buck and Joe Miller. The success of these candidates spoke to the restive mood of the Obama-era GOP base. But it also suggested that the proliferation of social media and information sources may have given primary candidates who would previously have been relegated to the margins opportunities to bypass elite opinion-shapers and reach the rank-and-file.

If this is true, then containing Gingrich now could be a serious problem for the GOP, no matter how problematic his nomination would be.

Shares