We all know that the cable-news echo chamber, in which we segregate ourselves into fiefdoms of Lord O'Reilly and Lady Maddow, isn't ideal for a functional democracy. But is living in a place where virtually everyone shares your basic political outlook -- where your opinions are rarely challenged by friends or neighbors -- really any different?

Writing in this week's New Yorker on why President Obama has been unable to bridge the partisan divide in Washington, Ryan Lizza points to a simple yet important factor: our tendency to live near people who always agree with us, creating a Congress without a true center. Is it possible that in building vibrant cities where we want to live, we've also created a frozen, extreme politics many of us abhor?

"It would be hard for any president to reverse this decades-long political trend," writes Lizza, "which began when segregationist Democrats in the South — Dixiecrats like Strom Thurmond — left the Party and became Republicans. Congress is polarized largely because Americans live in communities of like-minded people who elect more ideological representatives."

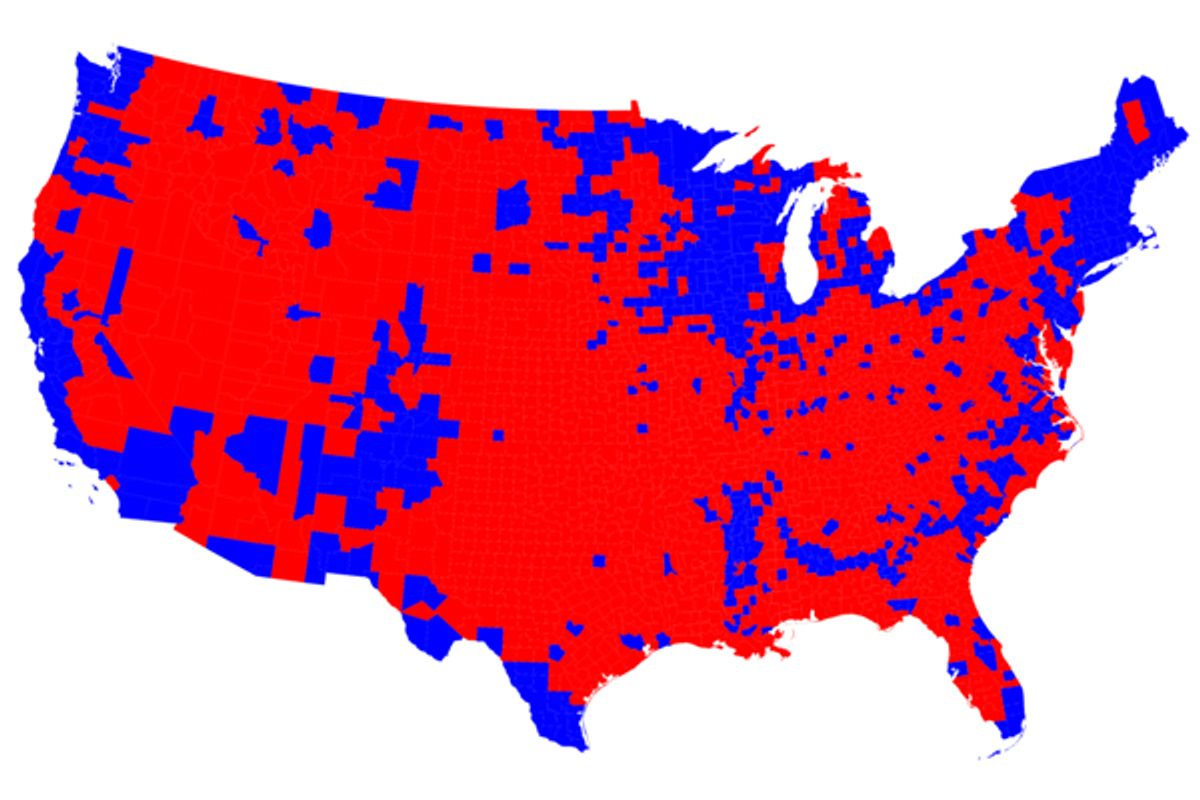

Lizza is dead right on this count: Americans are flocking to politically homogeneous communities. An analysis by the Pew Research Center found that "nearly half (48 percent) of all votes for president in 2008 were cast in counties that went either for Barack Obama or for John McCain by a margin of at least 20 percentage points." In other words, for about half of us, a total stranger could predict with unnerving accuracy whom we'll vote for knowing nothing about us but what neighborhood we live in.

Contrast that with 1976, when only 27 percent of voters lived in such counties, according to Bill Bishop and Robert Cushing, authors of "The Big Sort," a book about political segregation in America. By 1992, 38 percent of counties were delivering landslides. By 2000, the figure was 45 percent.

At the state level, too, the average voting margin has been growing ever wider. In 1976, only 19 states and Washington, D.C., could be considered truly red or blue. That left a whopping 31 swing states for candidates to pursue -- even hard-to-believe places like Oklahoma, Mississippi and California, each of which had final margins of victory of less than 3 percent.

Can you picture an electoral map so purple today? We've gotten to the point where merely being a Republican in brownstone Brooklyn is news enough to get you into the New York Times. A group of Ron Paul supporters is building its own town on the salt flats of West Texas, a libertarian utopia called Paulville where they can live according to their ideals (sort of like a '60s commune, but exactly the opposite).

The effects of all this political sorting can land extremist candidates in office, as Lizza points out. But at the neighborhood level, in our daily lives, how toxic is it, really?

Let's start with the upsides. There's no evidence that such grouping makes people seek out more partisan media, according to the book "Niche News: The Politics of News Choice" by Natalie Jomini Stroud. People in politically homogeneous communities tend to be more engaged in civic life. And even the very ability to cluster with like-minded folk is a sign that increasing wealth and mobility are allowing us to live in places that seem like a good fit.

And while the urbanist Edward Glaeser sees reason for concern, he preaches the gospel of perspective. "Yes, America has a lot of sorting, but we have always had a lot of heterogeneity," he wrote in the New York Sun in 2008, pointing out that between 1896 and 1936, just under 30 percent of the electoral votes were legitimately up for grabs, about the same (or even fewer) than today. He also wonders if political diversity is really as important as other kinds: "Racial segregation has fallen substantially. Any gulf in attitudes between red states and blue states today is dwarfed by the gulf in racial attitudes 50 years ago."

That said, it's clear that this kind of grouping isn't helpful. The Michele Bachmanns and Rick Santorums of the world would be fewer and farther between without it. And studies suggest that we ourselves might become more extreme when we always hang out with people who share our views -- one found that Republican-appointed judges rule more conservatively when the other judges on their panel are also Republicans.

Just as important, life in an echo chamber doesn't exactly lend itself to personal growth. Why do we abhor economic and racial segregation but not seem to mind dwelling in bubbles of groupthink? In this polarized era, maybe living side by side with people whose views are different than our own would help us see those people not as "others," but neighbors.

Shares