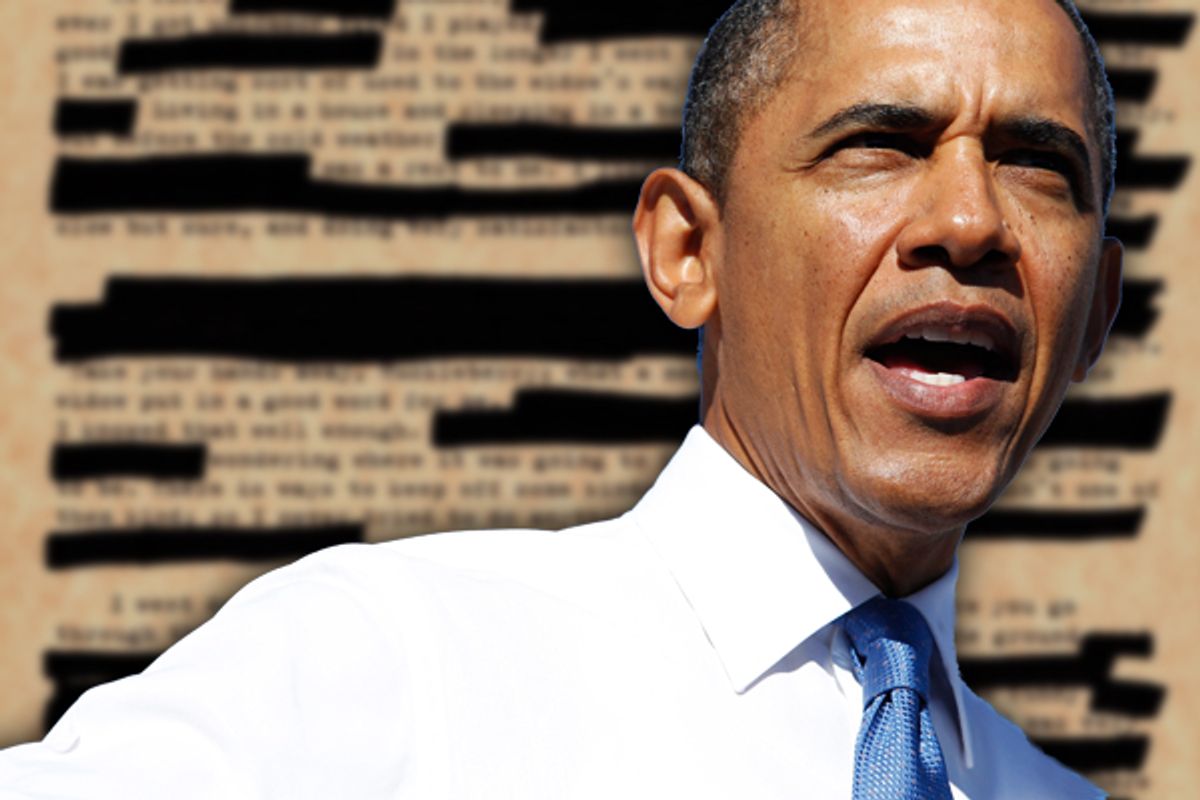

Several pieces of news about government secrecy emerged this week that show just how far away the United States has gotten from the principle of open government. The secrecy system is beyond control of the president.

First, we got a reminder that there are still 50,000 pages of government record relating to the JFK assassination that are being kept secret, nearly a half-century after that event. That's despite the 1992 passage of the JFK Act, which specifically called for the "expeditious" release of these records.

Second, the New York Times reported on an almost comically long delay in the government response to a Freedom of Information of Act request the newspaper filed in 1997. A response to the Times request was finally sent out earlier this week.

Any journalist who has attempted to use FOIA -- which was designed to open up the workings of a democratic government -- knows that the legal requirement of a response to a request within 20 days is entirely perfunctory. I've waited 18 months to get responses to certain requests. And the Times notes that instances of decade-long response times -- which can often amount to a rejection because of pressing need for information in, say, policy debates -- can be found at many federal agencies:

The National Security Archive, a nonprofit group based in Washington that is a heavy user of the Freedom of Information Act, reported last July 4, on the 45th anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the law, on some older cases that were still open. Those included a 1995 request for information on Pakistani surface-to-air missiles and a 1998 request to the George Bush Presidential Library for documents relating to the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland. The bombing happened in 1988.

Even more alarming than the FOIA story, though, is an item by longtime secrecy policy watcher Steven Aftergood reporting on the looming failure of the government to meet a deadline ordered by President Obama to process 400 million pages of records that are over 25 years old:

More than two years ago, President Obama set a December 31, 2013 deadline for completing the declassification processing of a backlog of more than 400 million pages of classified historical records that were over 25 years old. But judging from the limited progress to date, it now seems highly unlikely that the President’s directive will be fulfilled.

As of December 2011, following two years of operation, the National Declassification Center had completed the processing of only 26.6 million pages of the 400 million page backlog, according to the latest NDC semi-annual report. …

The looming failure to comply with an explicit presidential order is a sign of the growing autonomy of the secrecy system, which to a surprising extent is literally out of control.

The bolded section is a significant statement, especially coming from a sober expert who has been closely tracking these issues for years. This latest development is part of a pattern of executive orders on secrecy policy simply failing. Aftergood is arguing that, in effect, the secrecy system is operating in a way that is fundamentally at odds with democracy.

It's not all the Obama administration's fault. Part of the slowness of the declassification process is because of Congress.

The so-called Kyl-Lott amendment, which passed in the late 1990s, requires review to make sure documents don't include sensitive information relating to nuclear weapons. But it turns out some agencies ignored the original requirements of this law, so now the National Declassification Center has to perform another layer of processing on many of the documents, sometimes in consultation with other agencies.

Sheryl Shenberger, director of the National Declassification Center, which was created within the National Archives and Records Administration in late 2009, told Salon that the Kyl-Lott issue is a major cause of the delay. "[It] was just such a mishmash of poor quality or inconsistent quality," she said, referring to the failure of some agencies to comply with the Kyl-Lott law.

Still, the broader picture is that neither the administration nor Congress has prioritized declassification, which is how we got to this point. And this is all occurring under a president who issued an executive order on his first day in office that was supposed to ""usher in a new era in open government." The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

Shares