Save the confetti.

The two Democratic appointees to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled Tuesday that the California prohibition of gay marriage -- the infamous Proposition 8 -- violated the U.S. Constitution. Following the cautious counsel of a group of friends of the court, seasoned activists not part of the new litigation group that brought the suit, longtime liberal giant Judge Stephen Reinhardt passed up the opportunity to produce the gay Brown v. Board of Education.

Instead Reinhardt ruled on the narrowest possible grounds that Proposition 8 was unconstitutional, because it took away gays’ preexisting right to marry, extended to them a few months before by the California Supreme Court. No other state, not even the other states in the territory covered by the 9th Circuit, is affected by the ruling.

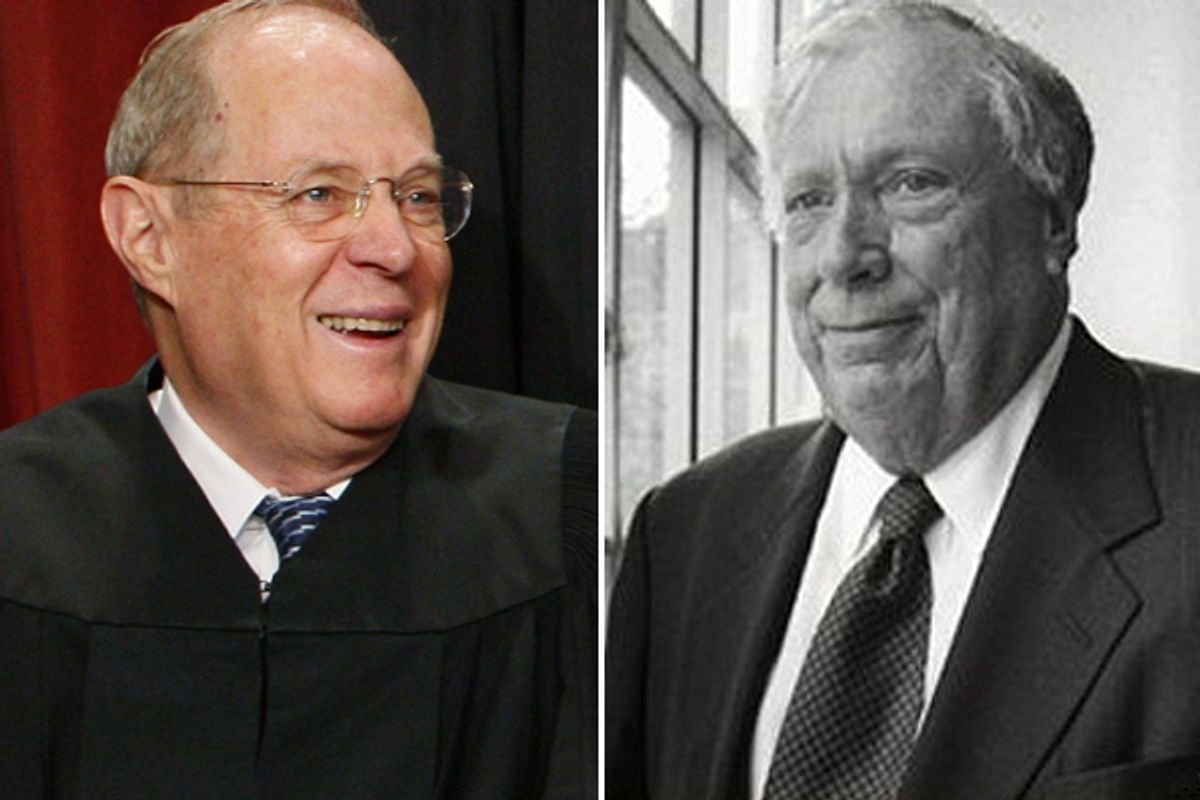

The opinion is an explicit appeal to Justice Kennedy, who wrote the original pro-gay Supreme Court opinion in Romer v. Evans, which involved a law that took away gay rights. It practically parrots the language of his opinion verbatim, offering him the opportunity to affirm their ruling and still duck the question of whether there is an overall constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

On their Tuesday conference call with the press after the decision, David Boies and Ted Olson, the famous lawyers behind the challenge, were lukewarm about the prospect that the Supreme Court would take their case as the opportunity to establish the constitutionality of same-sex marriage. This tone is notably different from the proclamations of national vindication that accompanied the filing of this suit after blue California handed them a black eye when they passed Proposition 8 four years ago.

They are right to be chary. Satisfying as it was to think of an avenging judiciary riding to the rescue of truth and justice, there hasn’t been a Warren Court for 40 years now. Even Judge Reinhardt’s narrow and cautious decision did not attract the vote of his Republican-nominated colleague on the panel. The political divide in the nation has long been reflected in the federal courts and nowhere as clearly as in this decision.

Thus, it’s all about Justice Kennedy, the only justice with even questionable allegiance right or left. Thanks to the long delays in trying Perry v. Brown, all the players now have a little more information about Justice Kennedy. When they filed, they knew that in 1996 and again in 2003 Justice Kennedy had written unequivocally pro-gay opinions in two landmark cases. Each year since the Perry case began, however, Justice Kennedy’s voting record, conventionally described as unpredictable at best, moves more to the right.

Last term, although he ordered thousands of inmates sprung from California’s obscenely crowded jails, almost all his other decisions served solidly conservative political interests: He protected the Westboro (“fags in hell”) Baptist Church's picketing of service members’ funerals, allowed Arizona to punish businesses that hire illegal aliens, but struck down Arizona’s law mandating public funding of elections.

In the prior term, although he again limited the cruelty of criminal punishment (no life sentences for juveniles), he approved the unlimited expenditure of political money in Citizens United, held that suspects had to ask for their right to remain silent, and temporarily allowed a big cross to remain up on the Mojave National Preserve. Academics spill pots trying to derive a grand theory for Justice Kennedy’s rulings from, say, the libertarian writings of John Locke, but Kennedy’s erratic decision-making is more about Mr. Dooley (“the law follows the election returns”) than Mr. Locke. A professional gambler would say the odds of a favorable outcome for gay rights have diminished since the Proposition 8 suit was filed.

Meanwhile, the boring and snail-like processes of democratic self-government have produced a surprising uptick in the prospects for same-sex marriage. New York state became the first big industrial state to pass a same-sex marriage law and prospects are good in Washington state and Maryland. The losers in a 2009 Maine referendum are predicting the first victory in a direct popular vote. And the New Jersey Legislature is challenging its Republican governor to veto the increasingly popular issue. The issue gets more favor with the public all the time; approval crossed the 50 percent mark last spring.

In light of these developments, the next step in the prudent strategy that generated a narrow decision designed to minimize the demands on the Supreme Court is to delay the moment of truth as long as possible. Fortunately, the complex processes of appeal present the plaintiffs with a chance to gum things up. In reaching the constitutional issue, the 9th Circuit actually ruled against the plaintiffs on the question of whether the anti-marriage defendant-intervenors had standing to appeal the trial court’s decision at all.

Rather than sitting back and waiting for the losing side to rush the substantive decision to the Supreme Court, the plaintiffs might take a shot at asking the whole 9th Circuit (en banc) to review the decision that the defendants have standing. Such an appeal would be transparently strategic, but by the time the parties have briefed the question of whether they’re even entitled to en banc rehearing on standing (since they won on the merits), plaintiffs will have bought several more precious months for the political climate to continue to turn in their favor. Even if they do not try to pursue an appeal from a decision that gave them a victory, briefing schedules are notoriously generous, and the plaintiffs would be well served to take advantage of that opportunity. Sometimes, even Shakespeare is wrong, and there is a real advantage to “the law’s delay.”

Shares