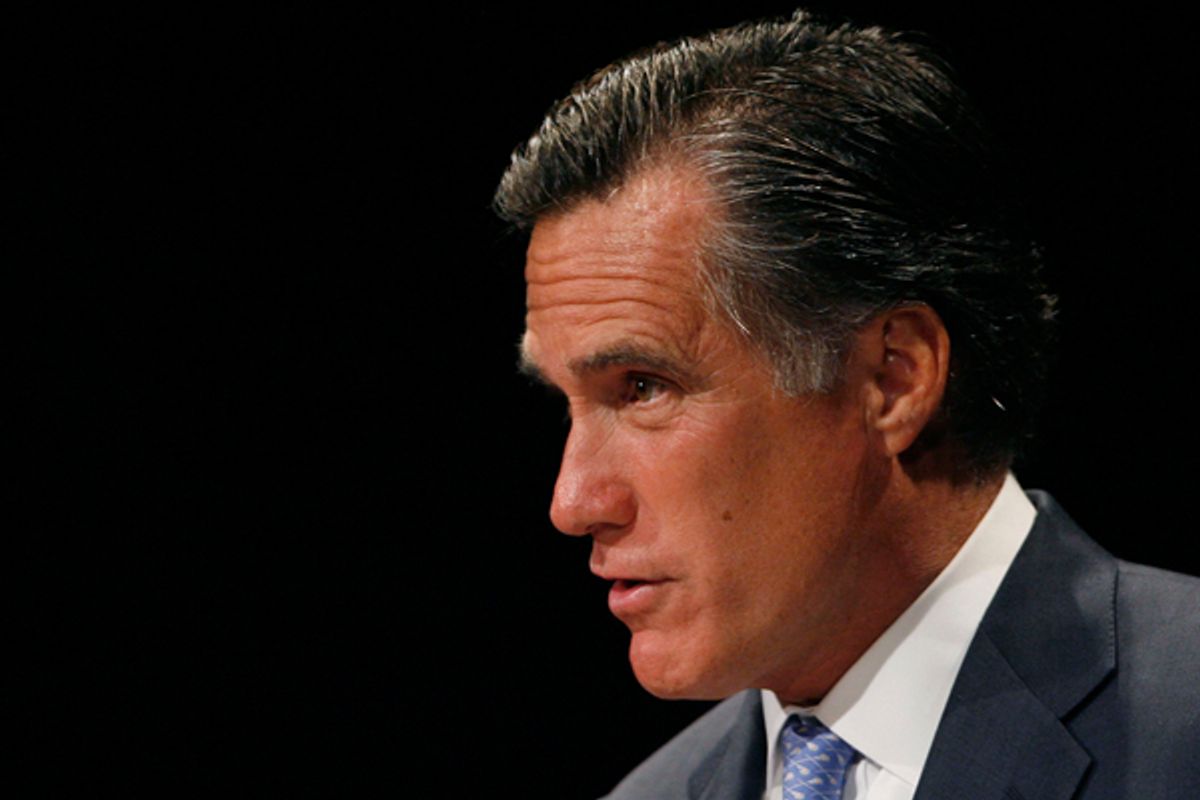

Frantic to stifle Rick Santorum's sudden momentum and to prevent Newt Gingrich from ever rising again, Mitt Romney spent the day after his surprise three-state meltdown hitting his two main rivals hard. The theme: Both Gingrich and Santorum are Washington insiders with histories of selling out conservative principles.

"When Republicans act like Democrats, they lose," Romney said in Atlanta on Wednesday, "And in Newt Gingrich’s case, he had to resign. In Rick Santorum’s case, he lost by the biggest margin of any Senate incumbent since 1980."

Romney and his campaign have been highlighting Gingrich's politically disastrous tenure as House speaker for weeks now, but the shot at Santorum's electoral history is new. His statement was true enough. When Santorum asked Pennsylvania voters for a third Senate term in 2006, they overwhelmingly rejected him, favoring Democrat Bob Casey by an 18-point margin. That defeat was likely a factor in Santorum's inability to gain any traction in the GOP race until the very end of 2011. Defying the "loser" label was -- and maybe still is -- a real challenge for Santorum.

But when it comes to raising the subject, Romney is a very imperfect messenger, because his own electoral history invites a label even uglier than "loser": coward.

The story goes back to 2006, when Santorum and Romney were grappling with the same troubling political landscape. Popular frustration with President Bush and the Republican Party was reaching poisonous heights and the signs were everywhere that Democrats would enjoy a successful cycle. That meant that both Santorum in light-blue Pennsylvania and Romney in dark-blue Massachusetts would be supremely vulnerable in their bids for reelection. Santorum's home state problems were made worse by his early-'00s emergence as a leading national culture war figure, while Romney's were exacerbated by his calculated evolution away from moderate pragmatism and toward ideological conservatism.

Further complicating each man's situation was presidential ambition. Both were seen as potential 2008 White House candidates, both fed the speculation, and both understood that a reelection loss in 2006 would severely harm -- and probably kill -- whatever '08 hopes they nursed.

There was one big difference, though. Faced with these discouraging realities -- and with an opponent, Casey, who came to the race with a beloved (in Pennsylvania) name and with unified support from national and state party leaders -- Santorum pressed ahead and ran anyway, carrying the banner for his party in what by Election Day had become an impossible climate. Romney didn't, announcing 11 months before the election that he wouldn't run.

It was a highly unusual move. Not since James Michael Curley in 1936 had an elected Massachusetts governor declined to seek a second term, and Curley did so only because he had a chance to run for the U.S. Senate. Romney claimed he was on track to achieve in his first term everything that he'd wanted to, but it was clear what was going on: He was scared of losing his '08 White House shot.

By that point, Romney's standing in Massachusetts was deteriorating and defeat in '06 was increasingly likely. In his first two years on the job, he'd displayed a genuine interest in reforming state government and building the state's Republican Party, but after the 2004 elections he began reinventing himself as an Iowa-friendly conservative true believer. He changed positions on key issues, adopted a strident ideological tone, and began traveling the early primary state circuit. This was not the governor that the Bay State's culturally liberal swing voters thought they were getting when they voted for him in 2002.

Even though Romney wasn't on the Massachusetts ballot in '06, he was a major factor in the state's election. His lieutenant governor, Kerry Healey, ran to succeed him, but Romney fatigue destroyed whatever chance she had. After announcing he wouldn't run, Romney accelerated his lurch to the right and stepped up his national travel, frequently taking shots at his home state in speeches to Republican audiences elsewhere. When word got back to Massachusetts, the locals weren't happy. Just before the November election, a poll found that Romney's popularity had fallen to its lowest level of his term. By a nearly 2-to-1 margin, voters said that Healey's ties to the outgoing governor made them less likely to back her.

On Election Day, she was routed by Deval Patrick, and the entire GOP slate went down with her. Since Michael Dukakis left office in 1990, Republicans had won every gubernatorial election, giving them invaluable beachhead in a state filled with Democrats. But now it was gone, and Romney was a big reason why: By reinventing himself in the middle of his term, he'd messed with the GOP's winning Massachusetts formula, and the entire party paid a price for it.

Of course, as Healey was getting drubbed, Romney was nowhere to be seen. He was off running for president, bragging to Iowans and South Carolinians about how he'd stood tall for conservative principles in Massachusetts. And when the results from Pennsylvania, where Santorum actually did stand tall for conservative principles in 2006, became official, Romney found himself with one less obstacle in his '08 path.

Shares