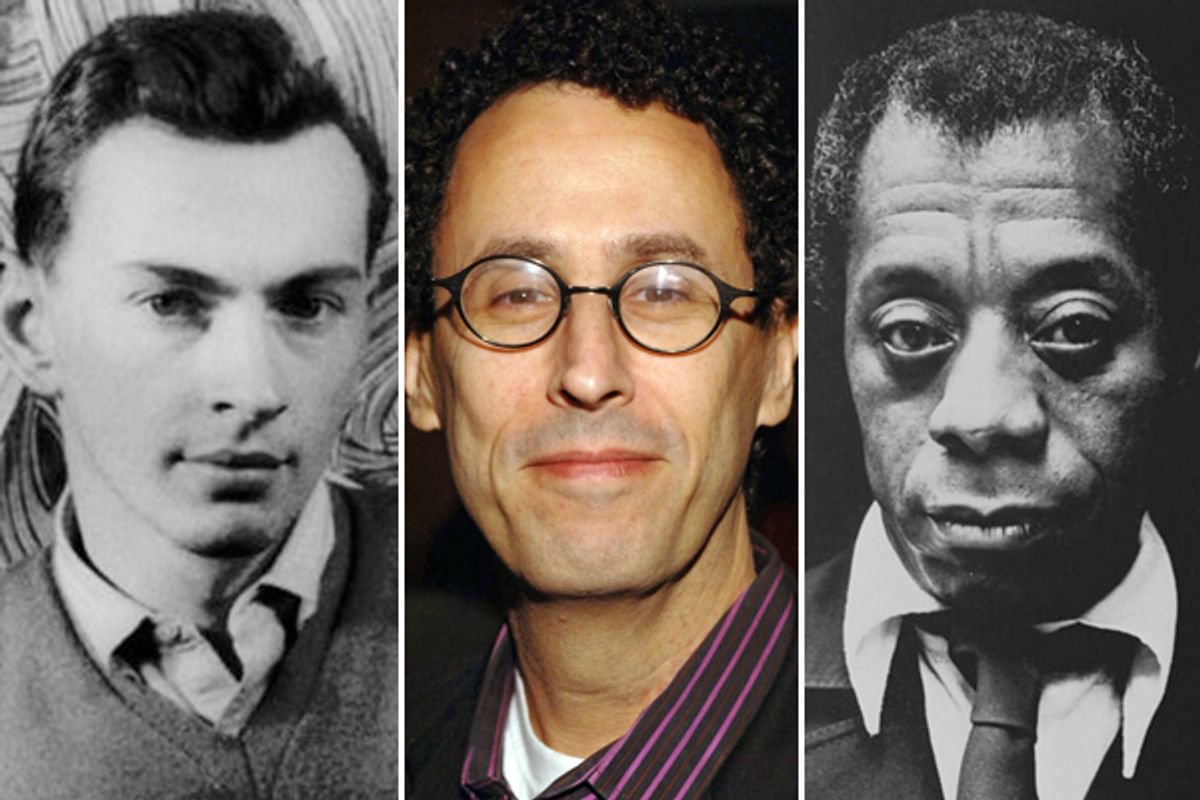

Gay life in America has utterly transformed itself since World War II. In the 1950s, homosexuality was a crime. Now, openly gay people are everywhere in popular culture, gay kids are coming out as early as elementary school and we can get even get married in a half-dozen states (including, soon, Washington). One of the most crucial, but least-talked about, reasons for this change is gay literature. Starting in the 1940s, a coterie of bold writers -- Gore Vidal, James Baldwin, Armistead Maupin and Tony Kushner, among many others -- played a central role in creating what we now think of as gay life. Their words gave voice to a segment of the American population that, for much of its history, was hidden away.

In his new book, "Eminent Outlaws," novelist Christopher Bram uses a series of complex portraits of America's most influential gay literary lions to argue for their position in the pantheon of American culture. The book covers expansive territory, charting the tumultuous relationship between Gore Vidal and Truman Capote, whose passionate hatred for one another lasted until the latter's death (Vidal called it a "good career move"). It describes Tennessee Williams' tortured relationship with his sexuality and gradual descent into alcoholic misery, James Baldwin's struggles against racism and Edmund White's eloquent reactions to the terror of AIDS. For anybody interested in gay culture, "Eminent Outlaws" offers a crucial and fascinating overview of decades of American literary history. It also raises the question: In an era when being gay is considered mainstream, does gay writing still matter?

Salon spoke to Bram (who is also the author of "The Father of Frankenstein," which was later turned into the film "Gods and Monsters") over the phone about Gore Vidal's importance, the death of the gay bookstore and the problem with gay men today.

As you point out in the book, literature has had an outsize role in the evolution of gay culture. Why do you think that is?

For the longest time, there were no gay characters or story lines in television or in the movies, so people had nowhere else to go but books for stories of gay life. After WWII there was suddenly a slew of them. It was surprising how many came so quickly. People could and wanted to write about it and the publishers would publish it. In my book I emphasize Capote's "Other Voices, Other Rooms" and Gore Vidal's "The City and the Pillar," but there were others. The mainstream houses backed away from gay material in the '50s but it was picked up by smaller presses, like Greenberg and Guild. Once it started it couldn't stop.

Why do you think the gay literary explosion happened right after World War II?

It was partly WWII itself. Gay boys who had grown up in the middle of nowhere entered the service, and found out they weren't alone. Alan Berube, in his book "Coming Out Under Fire," does a great job of painting this sudden awareness and huge change. Gay people also wanted to read about each other, and after WWII censorship for books loosened. Before, cities would ban any book with sexual content, and after WWII people could write about sex, even gay sex.

Gore Vidal is the major thread connecting the book. Do you think he's the most important figure in gay literature of the last 50 years?

Yes, but almost by accident. It's not a role he wanted. "The City and the Pillar" is a very gay book published early on in 1948. It sold very well but he got kicked in the teeth for writing it, and after that he played a little more coy. He adopted the strategy that there's no such thing as a homosexual, there's only a homosexual act; homosexual is an adjective and not a noun. He wrote "Myra Breckinridge" in the '60s, which is this wonderfully polymorphously perverse novel about a transsexual who rapes a straight man at one point. It's over the top and out there and was a huge bestseller. Then he started writing historical novels, which hardly dealt with homosexuality. But one of the most amazing things he wrote from a gay political point of view is the essay "Pink Triangle, Yellow Star," which was sparked by a very foolish bizarre essay by Midge Decter about gay men and their identity. He tore her essay to shreds, but he also argued that Jews and homosexuals had a lot in common, that they were both minorities that are in the same boat.

In the last few years we've seen the disappearance of a lot of gay bookstores around the country. What do you think this says about the state of gay literature?

That is a major change and it's an important and worrisome one. There are a couple of factors causing it. Independent bookstores have been in trouble for a while, struggling to compete first with super-chains and then Amazon and the Internet. Now the whole book business is going to transition, and even the super-chains are in trouble. Gay bookstores were always just keeping their heads above water. But I don't think it says so much about gay books in particular as it does about the book business.

Edmund White once wrote that "'Will & Grace' killed gay literature." Do you think he's right -- that the rise of gay TV and movies has made gay writing less appealing?

I think it's reduced the gay readership by 10 or 15 percent -- not a huge amount. And those were the people who didn't really enjoy reading anyway. For them, it was their only way to get gay stories. Now they don't have to. Independent film has dried up the same way indie bookstores have, so there's not as much gay film as there used to be just 4-5 years ago, but the change in TV is phenomenal. These shows matter-of-factly include gay story lines and characters and do really good jobs with them. They're not just here as comic relief, they're really fully fleshed out, well-drawn characters. These TV shows are following in the footsteps of Armistead Maupin's "Tales of the City" by including gay characters in this larger world.

Larry Kramer has very forcefully argued that young gay people these days don't respect their elders or their history. Do you get the sense that young gay men today are less interested in gay culture and literature than they were in the past?

Not really. I don't think the current younger generation is different from mine or even Larry's. In my generation, we hated our elders. We might like Christopher Isherwood, but there was a dislike of the older generation: "They got it all wrong, we're going to get it right." I think that's a natural generational dynamic; as time goes on you learn to keep what was good from the older generations and drop what was bad. I like the generations being different. Every generation wants to carve out their own space and to some extent it's going to mean rejecting the older generation.

But Larry Kramer isn't alone in feeling hurt by this. What do you think spurs this particular kind of anger among older gay men?

You're getting older and you know you're going to die, and you're not happy about that, so you take out your anger on the generation coming behind you. I teach at NYU, so I work with people in their early 20s and I expect us to have nothing in common but I'm always surprised by the books they like, the movies they like, the things we do have in common.

I also think older gay men are pissed off that young gay men seem entitled and don't seem to know what gay life was like in the '50s, '60s, '70s, and especially the '80s, during the first wave of the AIDS crisis.

Why should they know it? When they are aware of it, I'm pleased but I don't expect them to. They're lucky they didn't grow up with the hardships Larry's generation grew up with. My generation didn't have it as harsh as Larry's did, but I had it a little harsher than yours. It's only natural. You just kind of have to accept that.

In his famous essay in the Atlantic, Andrew Sullivan argued that we're witnessing the "end of gay culture," that it's splintering and dissolving as a result of mainstream acceptance.

Old gay culture wasn't that solid to begin with, and [literary gay men] were always a minority within a minority. Even when gay books were the only game in town, there were plenty of gay people who didn't read. For them being gay was about sex and going to bars and dancing. There's still gay culture around and it takes different shapes and forms. Gay bars don't play the same role in gay life they once did 10-15 years ago. The Internet has changed that too. I miss the gay bookstores, but I like the difference and the variety.

Do you think there's such a thing as a gay sensibility in literature?

When Jeff Weinstein, the New York culture critic, was asked if there was a gay sensibility and if it affected culture, he said, "No, there's no such thing as a gay sensibility and yes, it does affect culture." I feel that way. The only thing holding these men together is that these were men who were sexually attracted to men who would write about it and about how that mixed with the rest of their lives. For some writers, [their gayness] was just one more ingredient in the stew, like Armistead Maupin. For some, sex and love with other men was everything, like Edmund White. But even he mixed things up. His new book is about the friendship between a gay man and a straight man (though I think his best writing is his sexual writing).

Speaking of Edmund White, he has very strong feelings about writers, like Susan Sontag, who were famous but did not come out of the closet.

I think if she had actually written as a lesbian about lesbian life it would have given a whole other dimension to her work and she would have been a much more interesting and exciting writer than she was. But I just think of her as a writer [not a gay writer]. The other writer he talks about is Harold Brodky. Being unable to write directly about gay life made his prose weird and baroque and really blocked him as a writer. For me, their being in the closet becomes its own punishment.

A friend of mine recently told me that he thought we just don't have the kinds of great gay literary writers that we used to. I think we do, they're just not known as primarily gay writers. Do you think that's true?

There's good stuff being done by younger writers than the old war horses. It just hasn't gotten the attention it deserves. Paul Russell just did an amazing book last year called "The Unreal life of Sergei Nabokov," following Vladimir Nabokov's gay brother from pre-revolutionary Russia to Paris in the time of Cocteau to Nazi Germany. Peter Cameron's last book, "Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You," was very smart and beautifully written. Bob Smith, a comedian, did a wonderful novel called "Remembrance of Things I Forgot," about a gay man who travels through time to help his family and discovers he's been pursued by that arch-villain Dick Cheney. And then there's Rakesh Satyal, and the novel he published two years ago, "Blue Boy," about a gay 12-year-old boy in an Indian family in Cincinnati.

What gay books would you recommend as must-reads to a gay kid coming of age right now.

You could do far worse than Armistead's Maupin's "Tales of the City"; the entire series would be a great education in itself. Maupin imagines and records this world in San Francisco where gay people are just one more piece of the puzzle and accepted as such. And there's "Giovanni's Room" by James Baldwin. It's set in Paris in the 1950s, about a gay man who almost comes out but doesn't. It's very painful, beautifully written and it would show him what we've come away from. I'll be selfish and recommend one of mine, "Surprising Myself." It was my first novel, published in like 1987, and it's set in New York in the '70s -- the sexual golden age.

Shares