MEXICO CITY — At El Mirador, a cantina frequented by Mexico’s political and economic elite, you can see a fine selection of spirits and a menu that features dishes like pickled pigs’ feet and beef tongue tacos.

But what you won’t see are women.

But what you won’t see are women.

El Mirador, a relic from the country’s machista past, politely refuses to serve them. The bathroom has only a urinal and a sink.

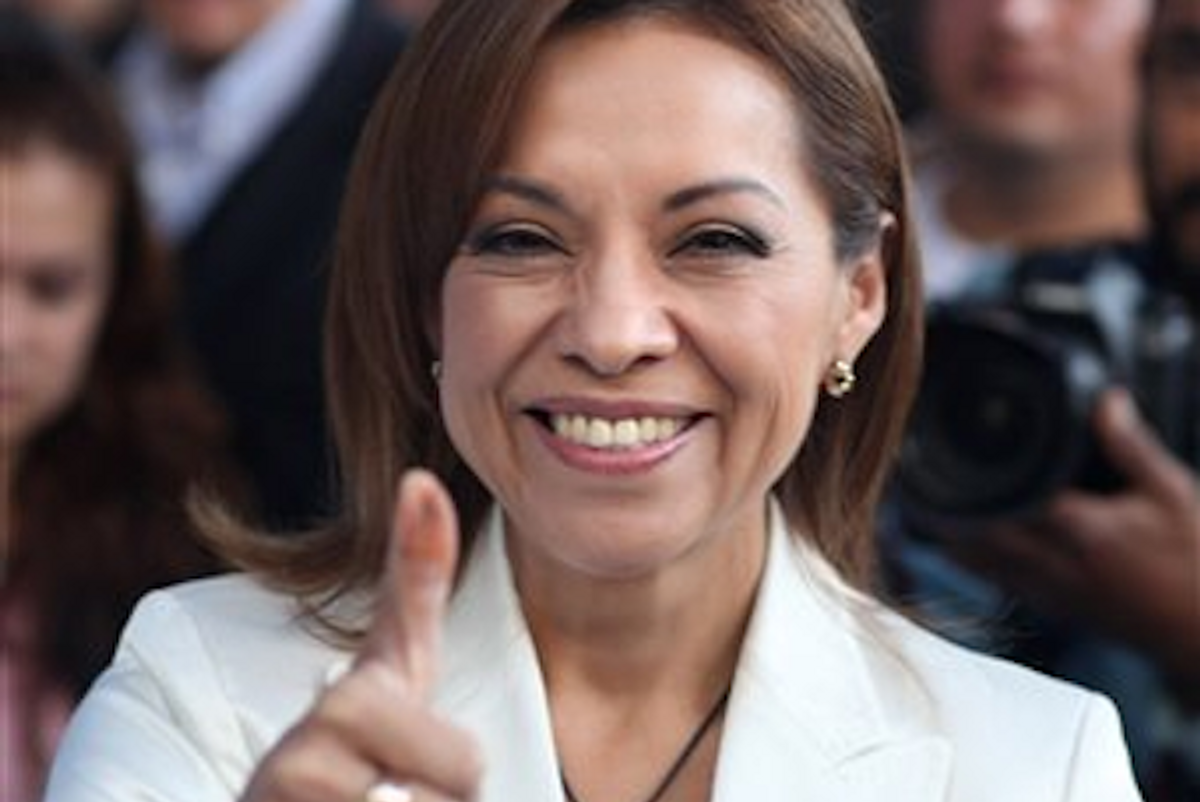

So it may have come as a surprise to some when Mexico's PAN party decided to nominate Josefina Vazquez Mota, a woman, for president – the first time a woman has ever been nominated by a major Mexican party.

Accepting her nomination, Vazquez Mota, a longtime government official, said, "I will be the first woman president of Mexico in history.”

Even if they are not yet welcome in the cantina at El Mirador, women are making noticeable inroads into other areas of Mexican political life.

With the real possibility that Mexico may join Latin American countries like Argentina, Brazil and Chile in electing a female to the highest office, her nomination marks a slow but steady erosion of Mexico’s macho culture, a way of life that lives on in the upper echelon of Mexican business world.

“Back in the 1950s all the cantinas in Mexico City were only for men. It’s the embedded machismo culture,” Ramon Peña-Franco, a former media analyst who worked for Mexico’s current leader Felipe Calderon.

Men gathered in cantinas to drink and play dominoes, while women stayed at home.

While the ban on women is not explicitly stated, it is enforced through the polite entreaties of waiters who explain the “tradition.” A woman in the men-only cantina might “make the other guests uncomfortable,” the Mirador manager said.

More than in the U.S. or the UK, the main stage of Mexico’s business arena continues to be dominated by men. However, more women have begun working in finance, information technology, media and manufacturing. Mexico has also seen an increasing number of female governors and cabinet members in the public sector.

And slowly, old social mores are beginning to evolve.

In 2006 many Mexican states updated the language used in marriage ceremonies, eliminating vows that asked men to treat their wives “with the magnanimity and generous benevolence that the strong should give to the weak,” and asked women to “give to her husband obedience [and] avoid awakening the most irritable and hard part of his character.”

Monica Morales, a financial analyst who was married in Mexico City in 2011, explained that the traditional language that was historically used in nuptial proceedings is too “macho.”

“Now, not even my grandmother would support it,” she said.

“Even my friends who want the most traditional weddings wouldn’t use it,” she said.

Some arenas of public life are evolving as well.

An electoral reform enacted in 2002 requires that major parties select female candidates for at least 30 percent of the seats they campaign for in the country’s congress. In 2003, the first election under the new rules, female candidates won 23 percent of the seats.

Now, women hold 30 percent of the seats in Mexico’s congress, compared to just 17 percent in the U.S.

Still, despite recent progress in the political arena, women have not yet broken through into the highest levels of Mexico’s corporate world.

Unlike in Mexico’s congress, very few seats in the country’s board rooms are filled by women. Only one of Mexico’s top 20 largest publicly traded companies has appointed a female board chair. Not one of Mexico’s largest companies has a female CEO.

When it comes to leading businesswomen in Mexico, Ramon listed “the owner of Grupo Modelo, Maria Asuncion Aramburuzabala. She’s the wealthiest woman in Mexico.”

“Other than that… I don’t think I can remember,” he said.

In July, Mexicans will vote to replace Felipe Calderon, whose six-year term has been plagued by violence from a five-year war on the drug cartels.

Many voters are ready for a change.

“This is a historic nomination, it has the potential to change the dynamics of the presidential race,” said Shannon O’Neil, a Mexico expert from the Council of Foreign Relations, a think-tank in New York.

It is still unclear whether Vazquez Mota, who has served both as secretary of social development, and later education, can convince voters to elect her.

Vazquez Mota’s main rival in the race to Los Pinos, the president’s office, is Enrique Peña Nieto, the candidate from the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI.

The party ruled Mexico as a de facto autocracy for seven decades until it was ousted from the presidency by a candidate from the PAN in 2000, is campaigning hard as well.

Peña Nieto is currently leading in the polls, and most analysts consider him to be the favorite.

Peña Nieto, though, has faced a number of missteps so far in his campaign. At a recent event in Guadalajara, he couldn’t name three books that have influenced his life. After failing to correctly state the price of a kilo of tortillas, a staple in most families’ diets, he shrugged off criticism, saying, “I’m not the woman of the house.”

Vestiges of the macho culture, after all, are still very much present in everyday Mexico.

As the rules change, other aspects of the country’s public life have evolved with time. In 2008, for instance, Mexico City banned smoking in bars and restaurants.

The cantinas begrudgingly complied.

Seated at a table at the Mirador, Ramon said, “Machismo is rooted, so it’s been harder [to change] in Mexico than anywhere else.”

By the exit, there was a table of men in their seventies finishing a game of dominos, getting ready to leave.

“The role of women in political life is changing,” Shannon, the Mexico expert, said.

“The real challenge for women in Mexico, and elsewhere, is to increase the numbers and the breadth of their participation and say in the way things are run.”

Shares