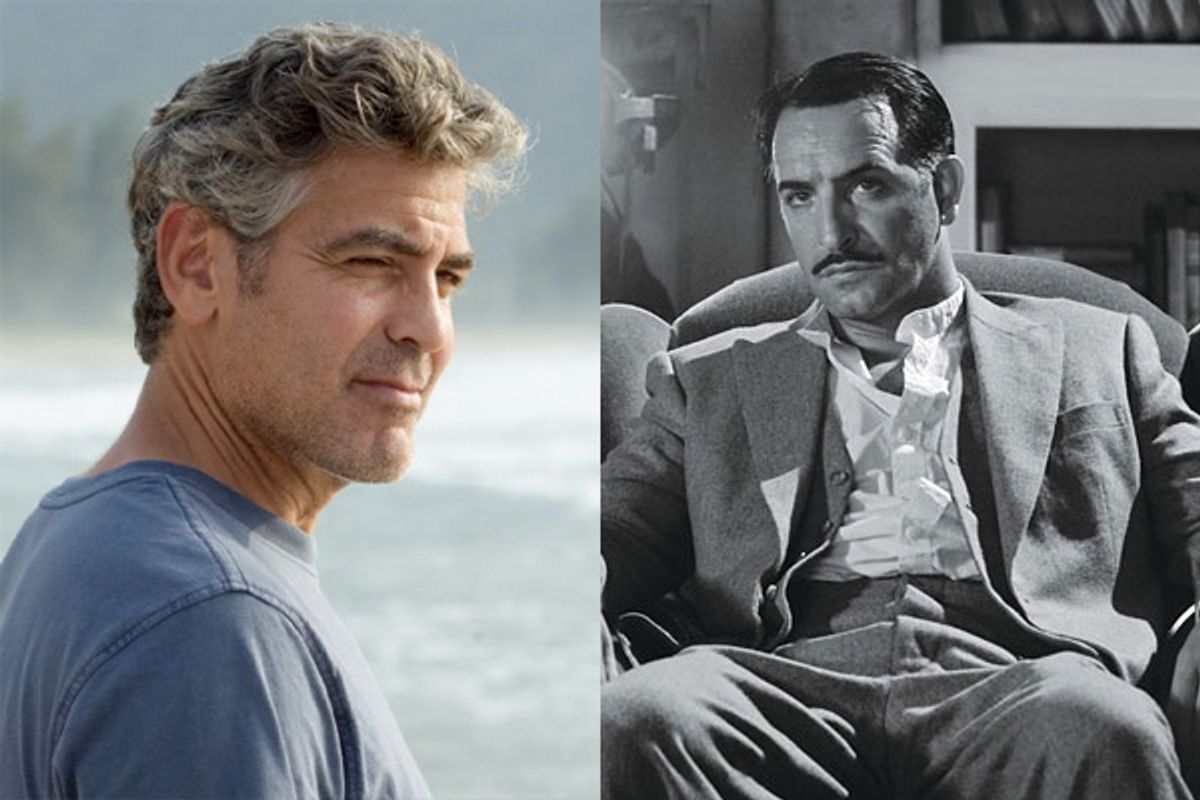

I can't be the only person who had a mixed, double reaction to George Clooney's big emotional scene near the end of Alexander Payne's "The Descendants," which seems destined to end up as the also-ran or bridegroom in this year's Oscar race. Wearing his bad haircut, his Hawaiian shirt and his 15 extra pounds as Honolulu lawyer Matt King, Clooney bends over his recumbent wife in her hospital bed, murmuring things to her that I won't specify, in case you haven't seen the movie yet. He calls her "my joy and my pain," lets a quite convincing tear run down his face, and leaves the audience digging for tissues.

Sure, the moment affected me -- but there was both something Pavlovian and something willed about the way I was affected. Part of me was right there with Matt and the severely ill wife he's learned a lot of unsettling things about, the daughters he's just getting to know and the big decision about selling unspoiled land on Kauai to developers that still lies ahead of him. (As if anybody in the viewing audience believes for a second that George Clooney is going to do that!) And part of me was thinking, "Boy, George is really acting his ass off right here, isn't he? I'm supposed to cry, right?"

Hardly ever in recent memory has the Academy Awards best-picture race been so bereft of drama or gossip or horse-race speculation with a week to go. I think everyone understands that in our sped-up media society the Oscar campaign just goes on too damn long, and the innate ridiculousness of all this focus on an election in which 6,000 people get to vote starts to show through. (I'd expect the ceremony to be moved to early or mid-February next year.) Even so, in most years there's some late-breaking scuttlebutt among the industry reporters who follow this stuff and quiz Academy members off the record. We often get word that some dark-horse candidate is starting to pick up steam (à la "Crash" in 2006), or breathless reports of a tightening two-way contest (between "The King's Speech" and "The Social Network," or "Slumdog Millionaire" and "Milk," or "The Departed" and "The Queen").

This year, though, zilch. Nobody even gets to complain about Harvey Weinstein's strong-arm tactics, because he doesn't need them. Mitt Romney can only dream of having the aura of inevitability that has clung to Michel Hazanavicius' "The Artist" throughout awards season. Oh, "Midnight in Paris" and "The Help" have had their Rick Santorum moments, I guess, but those faded out even more rapidly than Sen. Frothy Mixture has. So here we are, a week out from the big night in the No-Longer-Kodak Theatre, with Oscar's big prize all but awarded to a silent black-and-white film made by French people. If we can pull that fact free of the massive ennui we're all feeling about Oscar season this year, it remains objectively amazing. I mean, don't get me wrong: "The Artist" is agreeable lightweight entertainment, and I can see exactly why it appeals to the wounded, nostalgic and crisis-ridden industry insiders of the Academy. Jean Dujardin is an irresistible performer, and I bet he's been hitting the "apprenez l'anglais" CDs hard in preparation for his likely Hollywood career.

Still, the likely Oscar triumph of "The Artist," like the movie itself, is a novelty hit, a one-off parlor trick that demonstrates the weakened cultural position of the Academy Awards and the lack of confidence endemic to mainstream American filmmaking. As a spoof and tribute to the glories of Hollywood's silent age, "The Artist" is not especially subtle, but a lot of love and talent and pure high spirits went into making the movie, and that shows up on-screen. It's not a great film and may not even be an especially good one, but it's going to win the prize because it resounds with good cheer and confidence and willingness to entertain. Those are precisely the qualities usually associated with American cinema, good or bad, and precisely the qualities lacking in this year's other nominees.

When I made a mock-proposal for an alternate-universe Oscars in which mass-market hits like the "Harry Potter" or "Twilight" movies might compete against art-house films like "Melancholia" and "Take Shelter," I was trying to approach this same question from a different angle. Some readers assumed I was adopting some kind of bass-ackward, pseudo-contrarian Philistinism, and at least that's a change from the usual charge that I only like lesbian war films told backward and made in Hungarian. Please note that I didn't nominate "Transformers: Dark of the Moon," or "Thor," for my imaginary Oscars -- but I definitely prefer it when the Academy honors movies that don't apologize for their own existence, and that don't embrace a middle ground of mediocrity calculated to offend no one.

It's patently unfair to cook this crisis of confidence down to a single donkey tail and pin it on one movie. And I liked "The Descendants." Kind of, in parts, and up to a point. It's got quite a few modest, nice moments of emotional honesty, one of Clooney's best and subtlest performances (mainly when he's not saying anything) and a pleasant, half-dissolute Hawaiian vibe. But it's always going to be the American movie made by a name director that has George Clooney playing a bereaved husband and father, a spunky, sexy teenage daughter, slack-key guitar stylings and gorgeous tropical locations -- and that lost the best-picture award to that silent movie made by French people.

Believe me, I can hear your complaints, thanks to the one-way Panopticon that allows me to observe all of you out there in Internet-land. Criticizing "The Descendants" for not being some completely different kind of movie than it actually is is even more unfair than everything else I've said. Sure, sure. But the fact remains that on paper "The Descendants" sounds like an absolute, surefire Oscar winner -- a blend of laughter and tears; Hollywood's most beloved male star served in a pineapple, with a little umbrella -- and in practice it's a bit of a melancholy slog, a movie with a lot of dragged-out emotional scenes and not that many laughs, a movie people like well enough without feeling passionate about.

Furthermore, it's pointless to say that since Alexander Payne is a pretty-much-independent director who made the film he wanted to make, he's not to blame for the fact that it's almost but not quite an Oscar-winning movie. Let's face it, the movie Payne wanted to make is kind of a mess, starting with that mind-bendingly awful opening narration, in which Clooney-as-Matt pretty much tells us the whole story, including exactly how he feels about it and how we should too. In fact, whenever we draw near a dangerous scene where we're not quite sure what Matt's thinking or how he will react, Payne halts the forward progress of the narrative (which is already leisurely in the extreme) in order to have him talk to us in that literary voice that's not quite conversational and not quite internal. I have a hard time listening, though, over the Pounding Hammer of Obviousness.

Yes, this must be intentional. Payne is an experienced filmmaker who thinks, I guess, that he's being mildly unconventional here, dosing his tropical Mai Tai with a little Brechtian potato vodka or something. But mostly it comes off as forced and indulgent and a little bit off -- an attempt to create an Oscar moment -- which is exactly what I was talking about in the big scene where George Clooney made me cry.

I cried, in a pro-forma way, maybe because I'd sat through a long movie that was supposed to deliver an emotional catharsis. But the final shot, when Matt and his daughters snuggle wordlessly on the sofa, watching TV with a tub of ice cream, moved me on a much more profound and mysterious level. That scene represented "The Descendants" at its best, when Payne isn't trying so hard to deliver big emotions for which he's ill-suited, and is instead finding small, silent truths. If he had made that movie all the way through, instead of laboring so conspicuously to build an Oscar vehicle -- well, he might not be in the Academy Awards race at all. But at least he wouldn't be remembered forever for failing to beat out a French film where nobody talks.

Shares