“Not much of a defensive catcher, but a great bad-ball hitter,” my companion says over the rim of his beer glass.

We're on our third pint -- at least. My companion's literary escort, a fastidious professional in both dress and manner, checks her watch for the fourth time, smiling politely but somewhat nervously when I catch her at it. Her charge has got an 7 a.m. wakeup call, and she's tasked with getting him to the airport on time and in one piece. It's her job -- and I'm doing my best to disrupt it.

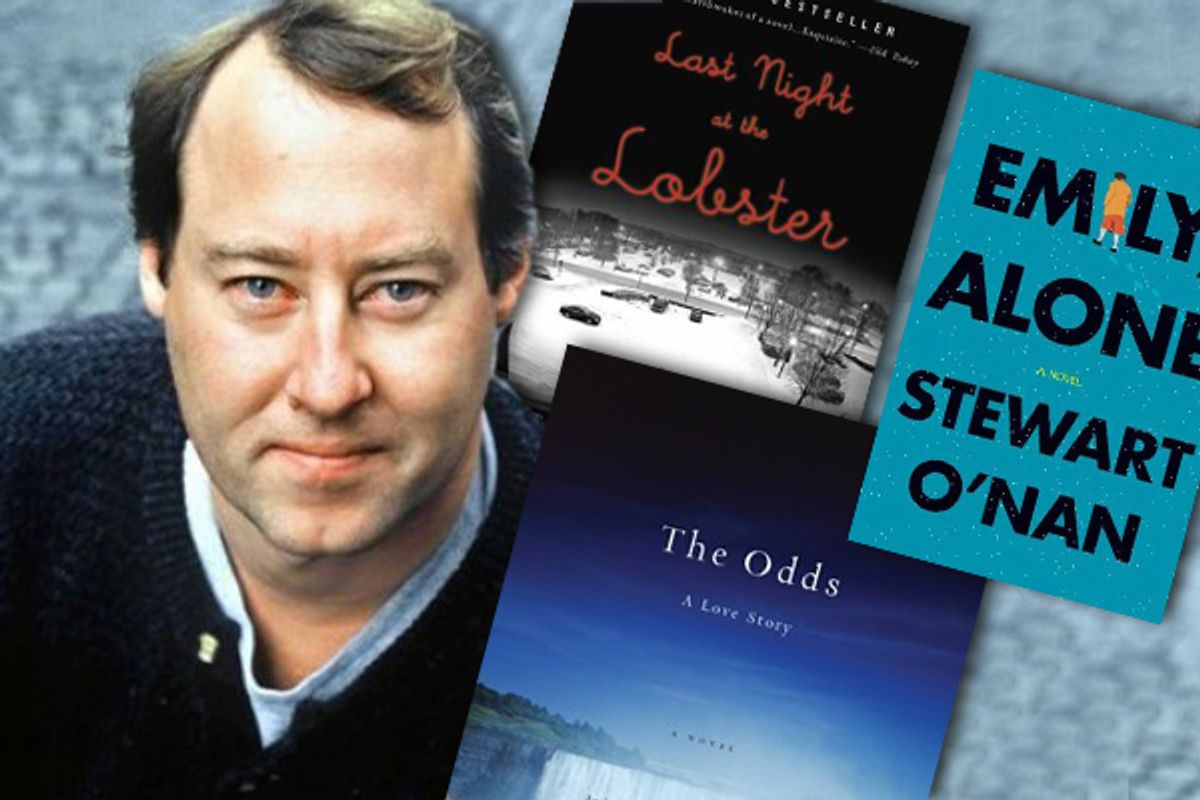

We find ourselves at a really dumb bar in Seattle's financial district, where I'm sitting across from the closest thing I've got to a living American literary idol. At 51, he still strikes a boyish cast with his high rosy cheeks, his mischievous eyes, and his well-worn Pittsburgh Pirates cap. But here's a guy who over the past two decades has given us 13 dazzlingly dynamic novels. In an age of literary snobbery, MFA elitism and postmodern irony, all of which have helped marginalize the novel, here's a guy who writes spectacularly without an ounce of pretension. A guy who writes about the people nobody else is writing about. An editor I know put it this way: “At a time when we are talking about class and income inequality, he's the novelist who has best captured the shifting state of America, what it is like to live outside of cities, to wrestle with what has happened to the working and middle classes outside of shiny urban places.”

I'm sitting across from Stewart O'Nan, and I'm thinking to myself: Is this guy our best working novelist?

“I think that's what I'd like to be as a writer,” he rejoins. “Like Manny Sanguillen, a guy taking swings at pitches that other writers would let pass.”

My mind turns immediately to "Last Night at the Lobster." How many writers would give us a novel revolving around the manager of a doomed Red Lobster restaurant upon its last night of operation? A spare, nearly perfect novel in which there are no unexpected plot twists, no overarching political themes, no heavy-handed cultural memes. And yet, through the sheer force and accumulation of luminous detail, through great pathos and humanity, a novel that elevates the quotidian to mythic heights, a novel that, at well under 200 pages, delivers a narrative heft that is rare.

His novels did not always employ this tiny aperture, nor this conspicuous lack of incident. His first novel, the darkly riveting “Snow Angels,” is driven by a murder. His deeply affecting sixth novel, “A Prayer for the Dying,” features the outbreak of a plague.

O'Nan cites his major influences as Stephen King and Flannery O'Connor, two names you're not likely to hear linked again any time soon, but make perfect sense when you read his oeuvre.

“I think the early books come from that collision of heavily plotted big-climax storytelling I grew up with (King, Bradbury, George A. Romero) and the more literary work I was just discovering (William Maxwell, Denis Johnson, Alice Munro), which focused more on accident and memory,” O'Nan says. “Early on, the body count is high, which often seems the consequence of not having faith, or of the world being an inhospitable place. The books after 'Wish You Were Here' seem more about characters' private lives than how they fit into or influence communities or deal with public upheavals like war or epidemics or politics. The focus is still that inner battle between hope and despair -- how we get through the days -- and the stakes are still high, but I find I'm leaning more toward Faulkner's idea of man not only enduring but prevailing. Lately, I suppose I see more strength in people.”

Growing up in broad-shouldered, working-class Pittsburgh, O'Nan says, has informed his awareness of how the larger changes in society, or the prevailing social norms, affect people in intimate ways. "The Odds," his newest novel, is a perfect example. Art and Marion Fowler are nothing if not ordinary people whose lives are disturbed and disrupted by external forces -- both economic and social -- imposed on them by the larger culture. The result is an intimate and deeply moving portrait of the high-stakes game that we call marriage, one in which the reader is bound, almost obligated, to recognize in some measure, with crystal clarity, their own marriage.

O'Nan is not without his critics, and they almost always seem to say the same thing, at least in recent years: Nothing happens in his stories. His fans might argue that's precisely the point. What O'Nan has done perhaps better than anybody else the past 10 years is deliver us the complexity, heartbreak and human drama of of everyday people living everyday lives.

“The story is always in service to the characters, and is only as long or short, or neat or ragged as it needs to be,” he says. “I work by feel, and follow what's hot. I may start with a plan to write a big 'It'-like horror novel set in an amusement park, but what comes out instead is 'Wish You Were Here,' a big but placid novel. Finally, the writing is just a medium -- the dream that rises from it is what's important.”

It's somewhere around midnight when we sit down for Mexican food and another round of beers. With much pleading and many assurances, we've finally managed to get out from under his clock-watching escort. For hours now, we've been volleying furiously back and forth between literature and baseball -- between Ernest Hemingway and Kent Tekulve, Al Oliver and Shirley Jackson, Chan Ho Park and "Gorky Park." Pressed further on what I consider his risk-taking, O'Nan is modest.

“I'm not sure the risks I take are any different from what other writers take, since we all serve at the pleasure of the reader,” he says. “What's the worst that can happen? You write a crappy book. No one writes a great book every time out, or even a good book (if Faulkner can't do it, and Woolf, why should you be exempt?). And not every reader is going to like every book. You just try to be true to your characters and get them across to the reader, and if you write a bad one, you write a bad one. You just hope you'll write a good one that people will take to heart, one that really means something to them. But you can't do that unless you're willing to fall on your face.”

Something tells me Manny Sanguillen knew that. In 5,062 at bats over a 13-year career, the man drew a mere 223 walks. That's some free-swinging, no doubt. His .296 career average is pretty damn impressive, particularly for a catcher of his era. And despite all that bad-ball swinging, he only struck out 331 times in nearly 1,500 games. And as O'Nan observes, Manny Sanguillen was always happy to be playing ball, always excited about being out there with his teammates.

“He's beloved, a big-hearted guy who took to Pittsburgh, and Pittsburghers recognize that, and, from the beginning, have taken him to our hearts.”

One can't help but wonder if Pittsburgh feels the same about O'Nan. They ought to. No disrespect to Mr. Sanguillen, but in my opinion, O'Nan is a better bad-ball hitter than Manny Sanguillen ever was. As a free swinger, I'd put Stewart O'Nan up there with hall-of-famer Kirby Puckett or Vladimir Guerrero. A guy you simply don't want to pitch to. But if you have to, here's what you do: You throw him your nastiest pitch and back up third base in a hurry.

Shares