What I am about to say will offend just about everybody, but it can’t be helped. Each of the major schools of thought about taxation in America — right, left and center — is trapped in its own particular fantasy world.

In its views on taxation, the American right is the most divorced from reality. As the fantasy economic plans of the various Republican presidential candidates prove, the right is still stuck in the Reagan era, calling for more and more tax cuts, with undefined spending cuts to be made at some future date, and with deficits and debt tolerated in the meantime — at least if Republicans control the political branches of the federal government.

The right’s derangement on the subject of taxation is often blamed on the anti-tax activist Grover Norquist, or tax-revolt populists like California’s Howard Jarvis in the 1970s. But it has deeper philosophical roots in the libertarian movement, which dominates the right’s economic policy, though not its foreign policy or social policy.

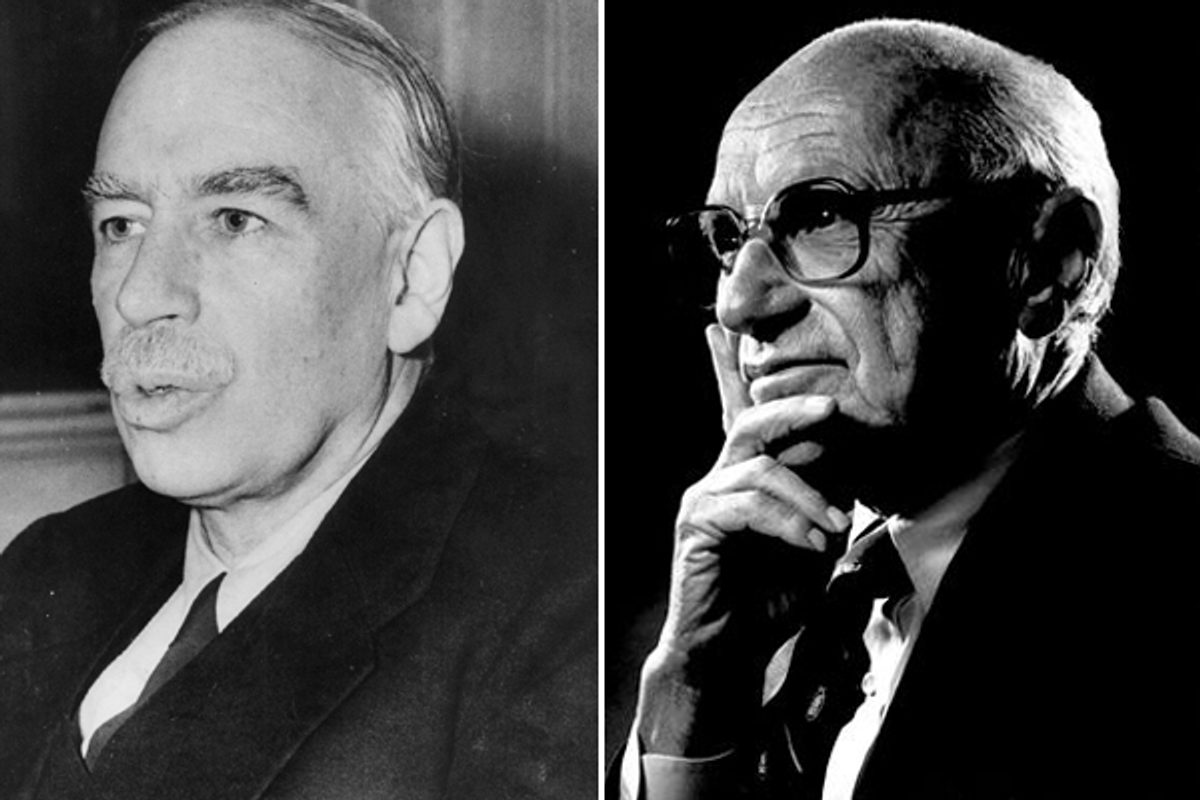

Back in the 1980s, when I was a young neoconservative (when that meant Cold War liberal, not Middle East-bombing neo-imperialist), my work helping William F. Buckley, Jr. on his book on national service, "Gratitude: Reflections on What We Owe to Our Country" (1990), took me to a conference on the subject of national service at the Hoover Institution. I found myself sitting at an outdoor lunch table with Milton Friedman, the patron saint of the Chicago School of free market economics. Like other neoconservatives of the time, I had no objections to the post-Roosevelt middle class welfare state, and I took the opportunity to ask Friedman, a libertarian (he preferred to call himself a “classical liberal”) how he justified taxation, in his philosophy.

“I don’t! I don’t!” he said, dramatically. “When the government taxes me, it’s the same as a robber pointing a gun at my head and demanding my money!” He pointed a finger at his head to make the point. Reporting this conversation to Buckley, I told him, “Milton Friedman may be a great economist, but if he thinks that taxation is theft, he is a moral and political idiot.” Unfortunately that particular brand of idiocy has become Republican orthodoxy.

To the extent that the radicals of the right (a better term than conservatives) admit the need for taxation, they tend to favor replacing all other taxes, including income and Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes, with a federal flat tax on consumption. There is a case to be made for a national consumption tax like a value-added tax or VAT (more on this below) but as one among several taxes, not as a replacement for all other kinds of taxes.

There is not a single advanced industrial democracy in the world that relies for its revenues on a single, flat national consumption tax. Not one. The absence of foreign examples may not bother right-wing proponents of American “exceptionalism” or uniqueness. But the rest of us must wonder, if funding all government spending from a single flat consumption tax is such a brilliant idea, why hasn’t some nation somewhere, perhaps a small nation, already tried the experiment? Libertarians can point to Chile as an example of a country that has attempted another of their panaceas, the privatization of Social Security. But they cannot point to any country that has adopted anything resembling their flat tax proposal.

Alas for the American left, the popular progressive alternative also fails the same test of international comparison. To judge from center-left journalism, more progressive opinion leaders oppose than support a federal consumption tax like a VAT, on the grounds that it would be regressive (a genuine problem, although one that can be ameliorated in various ways). But the Nordic welfare state, which represents a kind of utopia for much of the American center-left, rests on three revenue streams — not only income and payroll taxes, like those of the U.S., but also VAT revenues. The U.S. is unique among industrial democracies in its over-reliance on income and payroll taxes and its lack of a national consumption tax.

Now if you want to have a Nordic-style public spending without a Nordic-style VAT, you must jack up progressive income taxes, payroll taxes or both to extremely high levels. Much of the American left, it appears, would be comfortable with far higher progressive income taxes, funding much greater redistribution of income. Again, the question of international comparisons comes up: If this is a workable idea, why is that no other countries combine an ultra-progressive income tax with a much larger welfare state and no national consumption tax, not even the Nordic social democracies? Turnabout is fair play. If progressives gloat that no country in the world organizes its tax system along the lines favored by the flat-taxers of the right, conservatives can reply that not even the biggest and most generous European welfare states rely as much as American liberals would like on extremely progressive income taxes.

The political center, in the American tax debate, is represented by fiscally-conservative “deficit hawks” of both parties, who worry more about federal deficits and the national debt than the supply-siders of the right or the Keynesians of the left. Whether they are Republicans or Democrats, these earnest, rather solemn and puritanical folks tirelessly promote a bipartisan compromise: Raise revenues while lowering overall tax rates, by eliminating tax expenditures (“loopholes”) not only for the rich but also for the middle class.

In their own way, these centrists are as unworldly when it comes to the politics of taxation as the flat-taxers of the right or the redistributionists of the left. Bipartisan commissions can publish all the reports they want, but the odds that Congress will eliminate popular tax expenditures like the home mortgage interest deduction and the child tax credit are — as we say in Texas — slim to none, and Slim left town.

The centrist tax alternative, like the other two, fails the Other Country test. Centrist tax experts, not without reason, are afraid that lobbyists for special interests will riddle with any system of taxation with loopholes. They insist that all items should be taxed the same. On pain of losing membership in their professional guild, or so it seems, think-tank tax experts invariably say that the regressive effects of taxes on low-income Americans, including consumption taxes like a VAT, should be dealt with, not by exempting certain necessities like food and clothing from taxation, but by rebates.

For these thoughtful centrist tax experts, I have one question: Where is Rebate Land? Where is the country that taxes baby food at the same rate that it taxes cigarettes and alcohol and compensates by paying rebates to its citizens? In Europe? In Asia? In Latin America? Every democracy that has a VAT exempts certain items or taxes them at a lower rate than others. Exempting some items means VAT rates on others must be higher. So what? This upsets a few full-time tax experts and a few economics professors, but the rest of the human race somehow manages to live with the increased complexity that results in the tax code.

I don’t mean to discourage a vigorous debate about the future of American taxation. On the contrary, as Bruce Bartlett argues in his excellent, bestselling new guide to American tax reform, "The Benefit and the Burden," the American tax code needs periodic pruning if it is not to be overrun with special-interest weeds.

My point is that the three currently-popular options for tax reform — the conservative flat tax, the liberal ultra-progressive income tax and the centrist formula of lowering rates while slashing loopholes — are all unrealistic, in different ways. Sorry, conservatives — if the U.S. gets a VAT or another national consumption tax, it will be in addition to federal and income taxes, not in place of them. Sorry, progressives — while income taxes on the rich can indeed be raised considerably, there really is a point at which doing so will backfire by encouraging massive tax avoidance or capital flight. The experience of Europe suggests that it makes more sense to add a VAT to the mix of American federal taxes, if you want to fund a European-style middle-class welfare state.

Oh, and tax centrists — if your goal in your career is not just to trim but to completely eliminate tax expenditures for middle class Americans as well as the rich, you are going to have a sad, frustrated life.

Shares