It’s 10 a.m. and Todd Snider has just stepped away from an all-night poker game to talk with Salon about his new album, "Agnostic Hymns and Stoner Fables." Snider doesn’t sound tired — perhaps a bit hoarse from too much cigar smoke and too many bad hands, but he’s animated, charming, thoughtful, even funny.

Which may seem surprising given the subject matter of "Agnostic Hymns": He writes about right-wing hypocrisy, corrupt financial systems, the unknowability of God, and the pain of a broken heart, but his stoner cadence adds a bit of whimsy to the proceedings. That levity has always been crucial to Snider’s appeal, but lately, it’s distinguished him from other musicians who embrace sanctimony as a means of addressing the Great Recession. Snider may be angry, but he’s also genuinely curious, perhaps even slightly bemused by the exaggerations and mutations of human greed and self-justification. “At least it helps folk music, if nothing else,” he laughs at one point during our conversation.

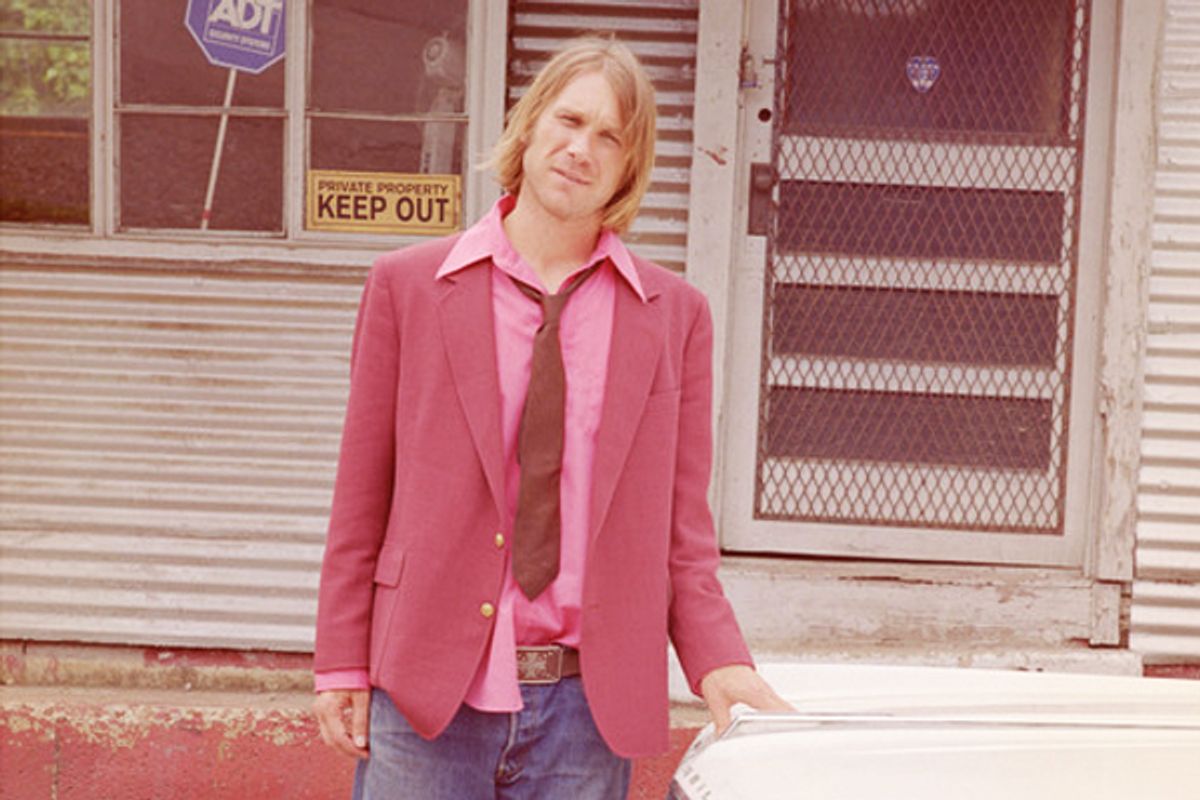

Born in Oregon but based in East Nashville — and it’s crucial to distinguish that bohemian enclave from Nashville proper — Snider emerged in the 1990s as a roots-rock singer and a sharp-eyed songwriter, yet the serious songs on his debut album, "Songs for the Daily Planet," were upstaged by a humorous hidden track, “Talking Seattle Grunge-Rock Blues.” Since then, he’s developed a keen eye for character and an ear for phrases that work as both punch lines and emotional gut punches.

Snider is fascinated by oddball Americans, writing wittily about FBI agents investigating the lyrics to “Louie Louie,” Catfish Hunter pitching a perfect game on LSD, even a ne’er-do-well political scion who becomes president of the United States of America. "Agnostic Hymns" adds some indelible characters and tunes to his catalog, but more than that it stands as a potent combination of anger and humor.

“New York Banker” was suggested to you by Rahm Emanuel. What’s the story behind that song?

Yeah. He’s my friend. I love that guy. He first came to see me in Washington, D.C., and he was about to go to some big meeting. The next time I met him was in Chicago. I was telling him about this song I was making up about the military-industrial complex. I was telling him it’s a stoner fable. All the stoners in the world are convinced that the world is run by these people that Eisenhower warned us about. He said, "You’d be surprised how much power the banks have now by comparison." He pointed out that there’s a song about "the military and the monetary" by Gil Scott Heron called “Work for Peace.” So it’s been tackled. He said, "What would Woody Guthrie do? He’d figure out a way to point out what the bankers are doing right now." So I thought, OK, I’ll try that. It’s not something I know much about, but I did some research on it. I read a book called “The Big Short,” and my father-in-law helped me find a person whose story I could tell.

It sounds like a good explanation for why the financial system is so blatantly and openly one-sided.

It’s unconscionable. I don’t get how that’s possible, but it is. I learned a lot doing this one song. It made me sit down and try to understand it. The guy who creates those pension funds with the teachers’ retirement money, he creates them to fail. That’s the thing … John Paulson created a thing called the Abacus deal [the agreement with Goldman Sachs that allowed Paulson to sell risky collateral debt obligations and then bet against them] and he’s just running around New York, isn’t he? That seems weird.

I think I know what a stoner fable is, but what exactly is an agnostic hymn?

I consider myself an evangelical agnostic, actually, which means I don’t know what I’m doing here and you don’t either. I feel like there aren’t any songs for that religion. They don’t even have a church for that, where people get together and hit tambourines. Anyway, I thought it would be interesting to come up with that kind of song — an agnostic hymn. There’s a song called “Too Soon to Tell” that I made up first: “It’s too soon to tell what happens when you die.” That song was originally titled “Agnostic Hymn” and then the song “In the Beginning” was originally titled “Stoner Fable.” A couple of my friends said that all the songs are that, so I came up with new titles for those two and implied that all the songs are agnostic hymns and stoner fables.

In “In the Beginning,” you sing about religion being the only thing that keeps the poor from rising up to kill the rich. That seems to be a major theme on this record. Was that intentional from the beginning, or an idea that emerged as you put the songs together?

I was just trying to make up the best songs I could and try to let myself say whatever. When it was done, it all felt right. I was listening back with a couple of my friends in Maryland, and they said, look, there’s a theme here. I didn’t realize until we were done that there are two occasions where it sounds like the singer is supporting the idea of poor-on-rich violence. I’m not not supporting it.

On your records, agnosticism seems to inform a very strict moral system.

I’ve always been a little put off by the idea that you need a reason to be nice to people. I’m just going to be fair with people, not because I’m afraid of what’s going to happen to me if I don’t, and not because I’m going to get good luck if I do. But because it’s right. I’m rooting for God as much as the next guy. I can’t think of anything I’d rather do than go to heaven with my wife and just sit there forever, but I’m not going to ignore logic or base my life on superstition, especially when it becomes something that’s going to impact another person.

It’s not actually a new theme for you, though, but something you’ve explored on previous records. Do you consider these protest songs?

I feel like I’ve always sung anti-suburban Christian songs. I grew up conservative Christian and all that, and now when someone tells me they’re conservative politically and also a Christian, I think, Why didn’t you just tell me that you’re a hydrogen bomb made out of dumb. Because those two ideas don’t gel. There’s one group that’s saying, Take everything you have and give it to the poor. And there’s another group that’s saying, Don’t tell me what to give to the poor. How can you join both groups? That’s like you’re joining Puppy Kickers Animal Rights of America. It just doesn’t gel, and that’s what I ran away from.

Are you concerned about alienating a potential audience?

I would almost like to alienate that audience that would disagree. If somebody takes offense to something that I’m saying, that would probably make me happy that I needled them a little bit.

The idea of music as a vehicle for protest seems to be popular right now. Do you identify at all with the Occupy movement?

On the chaotic side, I definitely identify with hippies in the park and Frisbees and weed and all that. But on a more linear side, I don’t see a plan. It’s almost like we saw the Tea Party and they looked dumb, so [we decided], Let’s show everybody our dumb. To a degree I get it. But even the Tea Party is a little more focused. I think the people at the bar I hang out at in East Nashville are offended by the 1 percent for two reasons: Their greed is just cruel, and their supposed connection to some sort of religion is embarrassing.

What attracted you to cover Jimmy Buffett’s “West Nashville Grand Ballroom Gown,” about a debutante who gives up high-class cotillions to hitchhike around the country? It was surprising to hear him espouse those ideas back in the 1970s.

That’s an interesting song of his. He wrote it when he lived in this town, and as I was hearing what I was saying on this record, I thought that song fit. It made me think of myself. I come from a jock house that I didn’t want to be a part of. I mean, I like to play hippie concerts, and I like Phish fans and stuff like that. A lot of them left nice homes to get away from greed and superstition.

One thing that definitely separates this album from a lot of other, for lack of a better word, “protest” albums is that this one is really funny.

Bill Hicks is probably my favorite — I would even call him a folk singer. He was three chords from a folk singer. I take a lot of his ideas. At the very least humor keeps you from being pretentious as you’re trying to be somebody that people go out to see on a Friday night. It’s good for vaudeville, and it’s also probably good for your heart. I’ve heard that laughter is pretty good for you, so I feel thankful that that’s a part of my life.

Shares