In Syria, fighting continues with a drastic toll on human life. In Libya, thousands remain imprisoned as allegations of torture conducted against former pro-Gadhafi fighters proliferate. Israel and the United States continue to debate the possibility of attacking Iran, which has pressed on with its nuclear program.

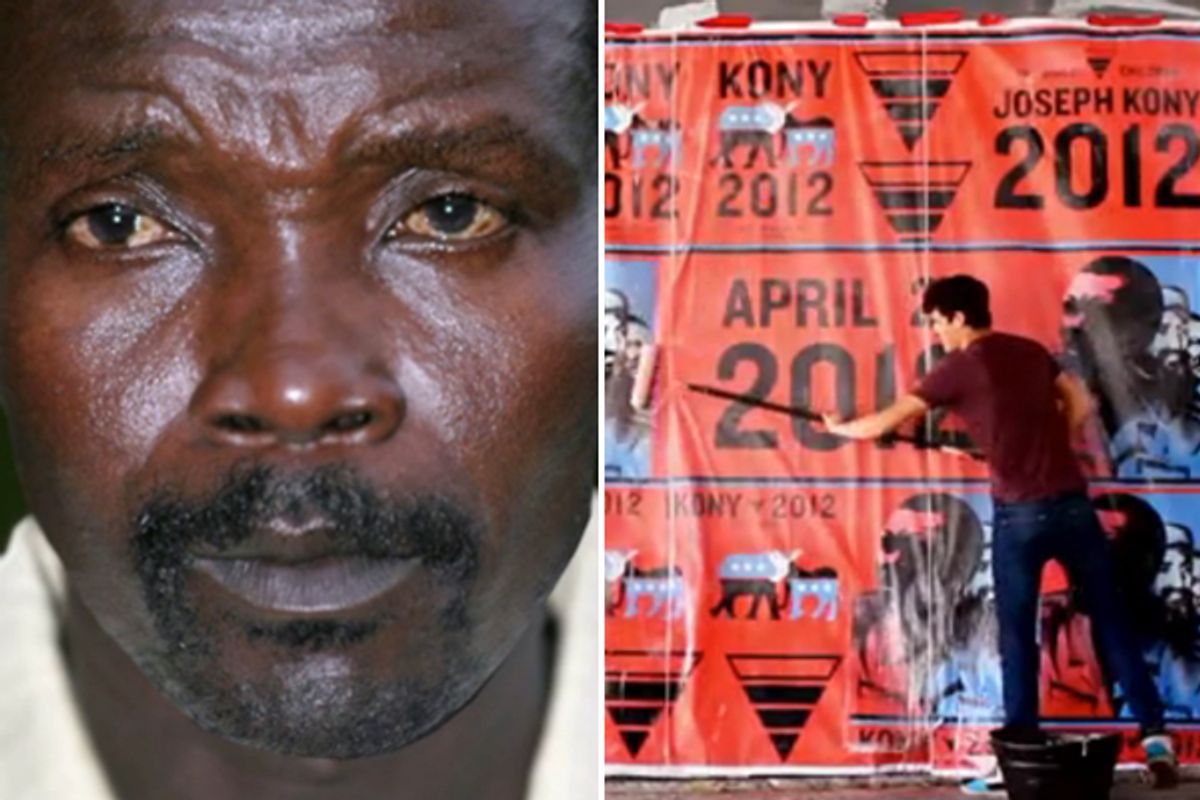

Yet, as a result of Invisible Children's film and campaign "KONY2012," the attention of much of the world has homed in on Joseph Kony, the leader of the Lord's Resistance Army, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court for his role in the abduction and murder of thousands of civilians in East Africa.

The San Diego-based organization seeks to spread the word about LRA atrocities, focusing particularly on the fate of children. They have built an impressive network in the U.S. and Canada. For the past several years, Invisible Children's strategy involved having groups "of five 'roadies' fan out to college campuses and churches throughout the United States and Canada.” In doing so, over the years Invisible Children has built a penetrating presence on Facebook, Twitter and other social media. With "KONY2012" they tapped into it – and then some.

The campaign has raised awareness -- indeed, it's success is perhaps unprecedented in the world of human rights viral campaigns. The number of people who have watched the film is likely to reach 100 million in the next few days. Yet, "KONY2012," in its simplistic portrayal of the situation facing northern Uganda and LRA-affected areas, has done both the truth and appropriate responses to the "LRA question" a disservice. It also raises questions about the future of human rights campaigns in the digital age.

The film itself, which centers around the dichotomous experience of a northern Ugandan victim, Jacob, and Gavin "Danger" Russell, the 5-year old son of Invisible Children's director, Jason "Radical" Russell, is powerful, in part, because it suggests that we, and our children, could all be Jacob. It distills a complex story into a "good versus evil," "bad guy-good guy" narrative that 5-year-olds like Gavin can understand. In the process, it strikes an emotional chord and taps into a latent moral outrage and guilt.

Some have suggested that the emotional connection the film instigates is part of the problem, and indeed it may be. Many have said it is manipulative and patronizing. But the most problematic and potentially dangerous aspect of the film is what it doesn't do, which is give an adequate understanding of the dilemmas and situation facing those who live in LRA-affected areas. Invisible Children's smooth message brutally obfuscates key realities about the conflict and other real and less costly solutions, in both human life and monetary terms. As Alex de Waal writes: “In elevating Kony to a global celebrity, the embodiment of evil, and advocating a military solution, the campaign isn’t just simplifying, it is irresponsibly naive.”

As many critics have pointed out, the crisis facing LRA-affected areas, which include northern Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, Sudan and South Sudan, is far more complex than the "KONY2012" filmmakers portray. It is a conflict that reaches as far back as 1986, and one in which atrocities have been committed not only by the LRA but by the government of Uganda. And it is one where military solutions have utterly and completely failed.

While the group has now said it will release a video-recorded response to criticism of the viral campaign, the solution Invisible Children's film proffers is yet another military operation aimed at capturing Kony -- a strategy that is both problematic and woefully misguided. Past military solutions, including Operation Iron Fist and Operation Lightning Thunder, have failed to disband the LRA or “stop” Joseph Kony. And in their wake, the LRA has retaliated with more violence, more killings and more abductions. Another military operation will inevitably result in the deaths of precisely the people campaigns like "KONY2012" intend to "save": children. That is the incontrovertible dilemma when military action is taken against any militant group made up of child soldiers, often used as human shields. In 2010, the U.N.'s Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict Radhika Coomaraswamy, warned that “we still live in a world with those who would use children as spies, soldiers and human shields,” while War Child Holland has noted that children abducted by the LRA “had to fight, spy, carry heavy loads or act as human shield or sex slave.”

Rather than getting decisive action on the issue, the pressure exerted by "KONY2012" may achieve just the opposite: superficial policies where the Obama administration is seen to be responding, but little else. Similar pressure led the administration to deploy 100 military “advisors” to Uganda in order to help in the fight against the LRA. With that decision, both the government of Uganda and the U.S. government could bask in the glory of legitimacy that they were taking the “terrorist threat” from the LRA seriously. Of course, many of those U.S. troops were already in Uganda when the announcement was made and many view their deployment as a tit-for-tat response for Uganda's engagement in Somalia, where the "Mogadishu Line" prevents the U.S. from actively engaging. "KONY2012" could very well lead to a similarly superficial response.

By taking this approach, the KONY2012 campaign is contributing to the narrow-minded narrative of the conflict as one between a lunatic, mystic madman whose band of terrorists kidnaps, rapes and murders against a legitimate, terror-fighting friend of the West. Meanwhile, the larger issues – the crimes committed on both sides of the conflict, the marginalization of the people of northern Uganda, and the systemic failures of regional governance – are nowhere to be found. As the widely respected scholar of northern Uganda Adam Branch has declared, “Invisible Children is a symptom, not a cause.”

While much of the criticism has taken a vitriolic character, some have tapped into larger debates about human rights activism in Africa and “he White Man's Burden.” The Nigerian-American novelist and photographer Teju Cole, for example, argues that “[f]rom Sachs to Kristof to Invisible Children to TED, the fastest growth industry in the U.S. is the White Savior Industrial Complex.” Writing in the Christian Science Monitor, Semha Araia, founder of the Diaspora African Women's Network, noted that Invisible Children “must be willing to use their media to amplify African voices, not simply their own. This isn’t about them.”

While advocates would like to believe the film draws on a trust in a common humanity and universal values, there is undoubtedly an "us" saving "them" element to the film. Taking a glance at Invisible Children's online staff directory, it is hard not to notice that all white-skinned employees stand in front of gray backgrounds while African staff appear before a token grass-roofed hut. Indeed, many have found it difficult to get beyond the implicit message that the solution to the crisis facing LRA-affected areas is in the hands of American policymakers, and not the affected Africans themselves. A common and powerful sentiment being expressed is that this portrayal of solutions strips the affected populations of their agency and voice.

But the "KONY2012" campaign also raises bigger questions about the nature and future of human rights advocacy. Will "KONY2012" change the way activism is done? Will human rights campaigns now be aimed at the 5-year old Gavin in all of us? Have we witnessed new heights in "slacktivism"?

While "KONY2012" leaves viewers with an understanding of northern Uganda and LRA-affected areas that is so simplified that it no longer even approximates either the realities or the attitudes of most victims and survivors, defenders ask: Is the awareness they raise not enough? Is that not the point?

To borrow a term Terry O'Reilly has coined, we have entered a new phase in the “age of persuasion.” It is generally believed that it is an age where precipitously declining attention spans are tethered to the globalization of mass media and social networks. In order to capture the imagination of the populace, conventional wisdom goes, campaigns – be they for human rights or laundry detergent – need to strive for simplicity of message. After all, they only have 30 seconds or three minutes to grab people's attention.

"KONY2012" complicates this long-held assumption. Invisible Children has captured the attention of millions with a 30-minute video. If 100 million people watch "KONY2012," that is 50 million hours of people's time. And yet, in those 30 minutes, the campaign purposefully maintains a dangerously simple message, preferring to communicate one so simple as to fit within the 140 characters of a single tweet.

Understanding need not be sacrificed on the false altar of awareness. It is possible to raise both awareness and understanding simultaneously. Choosing not to is just that – a choice. The viral videos and stories that characterized the Arab Spring, for example, shed light on emerging crises, the attitudes of participants and the challenges ahead without resorting to this kind of simplistic marketing. They increased our understanding and made us aware of the dramatic developments as they unfolded.

Many commentators have suggested that the film breeds "slacktivism" – lazy, proxy activism wherein active activism is replaced by dealing with latent moral outrage and guilt via the click of a "share" button. But, the problem with this critique is that it assumes that those who have clicked are activists in the first place. As Zeynep Tufekci has rightly noted, “[s]ince these so-called 'slacktivists' were never activists to begin with, they are not in dereliction of their activist duties.”

The bigger concern about this new form of viral activism is that participating in the "KONY2012" phenomenon and campaigns of its ilk may replace real and appropriate responses to crises with quick-fix, cathartic absolution of guilt.

There is a real option on the table where both international and local actors can play a vital role: support the re-ignition of peace negotiations. Talks between the LRA and the government of Uganda, in Juba, South Sudan, took place between 2006 and 2008. While they ultimately failed to produce a comprehensive peace agreement, they did deliver stability and order or what many northern Ugandans refer to as the “silence of the guns.” Numerous local groups, including the Acholi Religious Leader's Peace Initiative, are working on getting the parties back to the table. Doing so, of course, will require learning and applying lessons from past negotiations, notably ensuring that all regional parties to the war participate.

Of course, laying out those past negotiations may make for a far less digestible viral video.

Shares