Last month, Gallup reported that despite economic crises brought on by financial deregulation, far more Americans still worry that there will be too much regulation rather than not enough. No doubt, the survey results reflect the triumph of conservative "free-market" rhetoric in equating regulation with job loss in the American psyche. That's a victory of ideology over economic reality, because, as Businessweek recently noted, regulations are hardly job killers. Instead, the magazine points out, they typically "wind up creating about as many jobs as they kill." In the process, they also mitigate major social problems, as Coca-Cola and Pepsi just proved.

In a move that could serve as the singular parable about the value of regulation, the two soft drink behemoths recently announced they "are making changes to the production of an ingredient in their namesake colas to avoid the need to label the packages with a cancer warning," according to Reuters. The shift comes in the face of a science-based decision to designate the ingredient a potential carcinogen, which then subjected it to a California regulation mandating disclosure of such compounds to consumers.

Over the course of history, the most famous regulations -- not the free market -- have reduced everything from wage theft to pollution to financial implosions to mass food poisoning. Less well remembered -- but equally important -- is that subset of regulations that simply force companies to tell us exactly what is in their products. Those empower consumers to make more informed decisions about where to spend their money -- and, as last week showed, they often end up prompting companies to preemptively produce their wares in a more responsible manner.

Even to those who think the government shouldn't set rules dictating the terms of production, basic disclosure regulations should be considered a no-brainer in a functioning capitalist economy. Such regulations don't say a product cannot be produced -- they simply say that when the product is produced, consumers have a right to know what is in it. Why would anyone argue against that?

Why? Because money -- Big Money -- is involved.

Almost every time a disclosure regulation has been proposed, the moneyed interests involved mobilize to stop them -- or at least slow them down. In the pursuit of profit, industries would rather keep consumers in the dark than be forced to answer pesky questions about human health, the environment and other such concerns. Consider just the last few years:

- The oil and gas industry has fought tooth and nail against state legislative proposals to at least disclose what kinds of toxic chemicals they are pumping into the ground when they engage in hydrofracturing.

- Major meat producers have opposed country-of-origin labeling regulations, successfully using the World Trade Organization to knock down those rules so as to keep consumers in the dark about where their meat is from.

- Monsanto, the agriculture bio-tech giant, has used its political clout to stop regulatory proposals in the United States that would force food companies to tell consumers whether products included genetically modified ingredients. But that's not all: The corporate colossus has also convinced the U.S. government to use its power to try to gut other nations' GMO labeling laws, too.

- The cosmetics industry has not only stopped state legislatures from regulations banning suspected toxins in beauty products, but has also ensured that the federal government regulations do not require the disclosure of most of those toxins. "Since the federal cosmetics law was written more than 70 years ago, the FDA has banned just eight out of the 12,000-plus ingredients used in cosmetics," notes activist Annie Leonard. "The FDA doesn't even require all of the ingredients to be listed on the label."

- Most recently, the tobacco industry has used the federal court system to invalidate regulations mandating explicit warning labels about the adverse effects of smoking on human health.

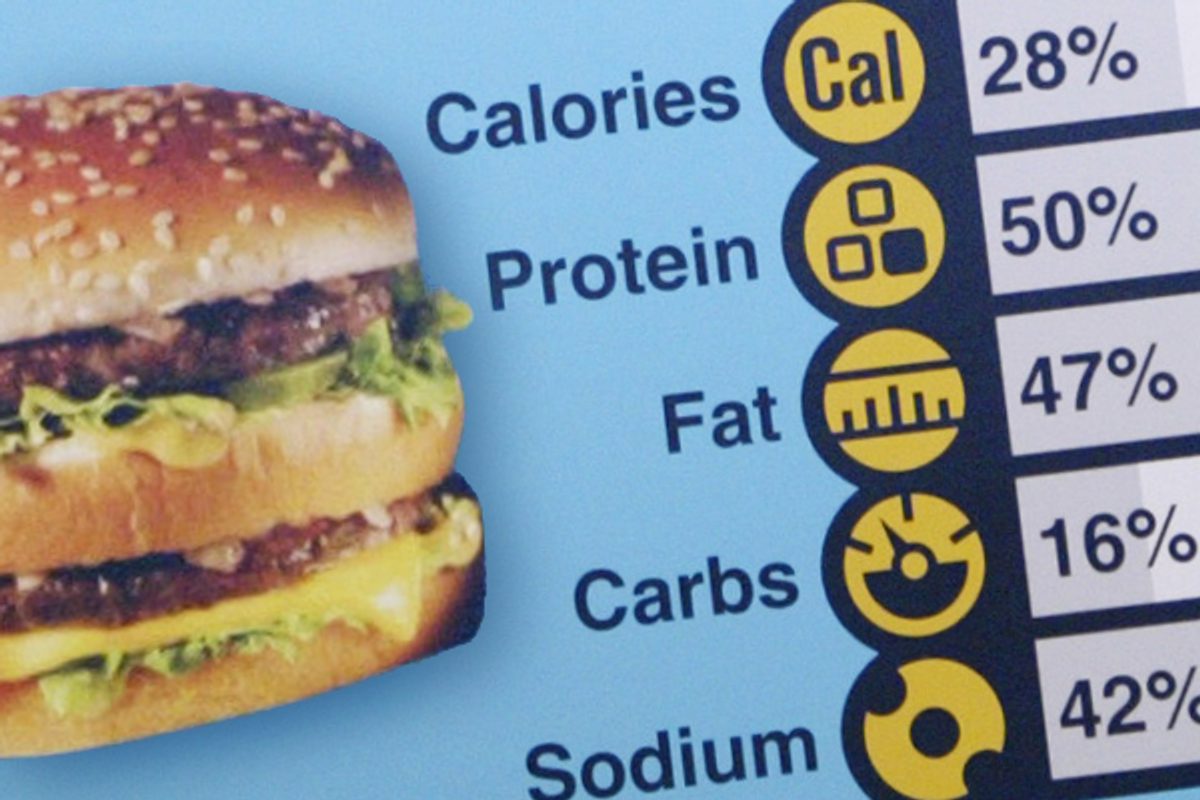

Let's be clear: These are but a few of many examples of a larger corporate opposition to basic disclosure. It is an opposition that is driven by corporations invested in the status quo -- and from a business perspective, it is entirely practical because industries know full well that public information tends to change consumer behavior. Indeed, a 2000 study by Texas A&M researchers found that now-standard nutrition labels on food substantially "decreased individuals' average daily intakes of calories from total fat and saturated fat, cholesterol and sodium." Likewise, a 2010 Stanford University study, for example, found that calorie labeling at Starbucks resulted in a 6 percent decline in the average calories per transaction (and, countering those who claim that such regulations harm profits, Starbucks actually increased its profits in the process).

While some companies like Coca-Cola and Pepsi change their products in the face of labeling regulations, other corporations have tried to preempt such regulations and the subsequent shift in consumer behavior by rolling out their own reassuring labels. Rather than change their products, these firms have opted to try to either mislead consumers entirely or at least confuse them with information overload.

In terms of full-on misleading, as the New York Times reported in a 2011 story about the proliferation of "functional food" labels, federal regulators are now concerned "that some packaged foods that scream healthy on their labels are in fact no healthier than many ordinary brands." When it comes to merely overloading the consumer with too much information, the already bewildering chaos at the supermarket could get even more perplexing in the coming months with Wal-Mart rolling out its own "Great for You" label for foods it deems healthy.

Information, as the old saying goes, is power. And when we consider all of this in totality, it's clear corporate America recognizes the truth in the aphorism. Companies, in other words, understand that for all the fact-free vitriol constantly thrown at the basic concept of regulation, government regulations that increase information simply expand consumer power over the market. That may threaten companies that want to continue poisoning us, but as a political goal, consumer empowerment shouldn't be so controversial. Continuing to keep consumers in the dark and powerless should be.

Shares