Six hours. It’s remarkable for the Supreme Court to allow that much time for argument of a single case. But then, it’s remarkable that the challenge to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA for short) is in the Supreme Court at all. Constitutional claims that would have seemed obviously ridiculous a couple of years ago – and, I expect, will be deemed obviously ridiculous a couple of years from now – are treated with solemn gravity by the Court. The justices are evidently looking forward to resolving these claims.

And that’s why it is unlikely that the Court will accept Monday’s invitation to throw the whole case out on jurisdictional grounds, without ever reaching the merits. Before a court can hear any case, it has to decide whether it has the authority to do it. The central challenge in the case is to the ACA’s “mandate,” which deducts a penalty from the tax refunds of persons who go without health insurance. Monday morning’s oral argument in the Court focused on an obscure statute called the Anti-Injunction Act of 1867, which states that “no suit for the purpose of restraining the assessment or collection of any tax shall be maintained in any court by any person.” Several lower court judges have concluded that this language means no one can challenge the ACA until they have paid the penalty. That would delay the litigation for years, since no penalties will be collected until 2015.

The Obama administration initially embraced this argument, but eventually abandoned it, deciding that it would be better to resolve uncertainty about the law’s constitutionality as soon as possible. The Court, however, decided that it could not ignore arguments that had convinced several of the judges below, so it appointed its own attorney, Robert Long, to argue that case.

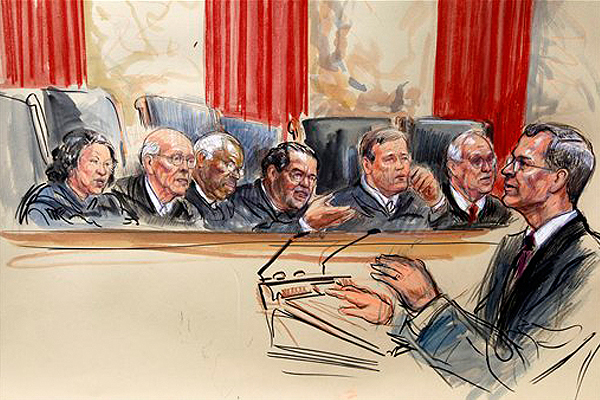

Then it gave Mr. Long a very hard time. He was peppered with skeptical questions from both liberals and conservatives on the Court, neither of whom seemed to want to extract such a surprising result from a law that Long himself admitted is not “a perfect model of clarity.” And some of the judges went out of their way to help out the attorneys on the other side, which now included both the administration and its adversaries: All of the parties want the Court to hear this case.

Still, the Court’s desire to fend off the jurisdictional issue may be bad news for one of the administration’s substantive arguments, that the mandate is constitutional under Congress’s power to tax. Justice Samuel Alito asked Solicitor General Don Verrilli: “Has the Court ever held that something that is a tax for purposes of the taxing power under the Constitution is not a tax under the Anti-Injunction Act?” Verrilli had a respectable answer: “the form of words doesn’t have a dispositive effect” on the question of whether the taxing power has been exercised, but the precise choice of words does determine, as a technical matter, whether the Anti-Injunction Act applies. But it would be hard to translate that result into a form that will make sense in the popular press. And, as I’ll explain below, the Court is likely to be focused intensely on the likely popular reaction to its decision.

The other reason why the Court is likely to want to reach the merits has to do with the trajectory of this decision. As I said at the outset, it is weird for this argument to be here in the first place. The mandate is obviously constitutional under well-settled precedent. Congress has the power, under the Commerce Clause, to regulate insurance, and so to mandate that insurers cover people with preexisting medical conditions. (None of the challengers dispute this.) Under the Necessary and Proper Clause, it may choose any convenient means to carry out this end. The mandate is clearly helpful, and may even be absolutely necessary, to Congress’s purpose. Therefore it is constitutional. (This argument is elaborated here.) It’s not even necessary to reach the argument that the mandate is valid under the taxing power. It’s already valid before we get to that question.

From the beginning, challengers to the statute have danced around this argument, sometimes going so far as to read the Necessary and Proper Clause out of the Constitution altogether. Or they have argued that the Court must craft some new limit on federal power, ignoring the fact that there are already well-established limits (which, unfortunately for them, the mandate does not come close to violating). The fact that so many people (including, I am very sorry to say, some law professors who are friends of mine) have converged around such weak arguments is a specimen of the collective madness that occasionally besets otherwise well-functioning civilizations, like the McCarthy red scare of the 1950s, or the Salem witch trials.

The explanation seems to be the remarkable anti-Obama hysteria that has developed. Barack Obama, the poor sap, thought that he could get healthcare reform passed by just adopting the Republican proposal: instead of creating a massive new government health care bureaucracy – something like what we already have with Social Security – we’ll contract with the private sector to deliver healthcare to all these uninsured people. A prescription for bipartisan consensus and changing the tone of Washington, right? Imagine his surprise when he was told that Social Security-type Big Government is perfectly acceptable – none of the challengers want to challenge Social Security, which is another kind of government-mandated insurance – but this Smaller Government is monstrous tyranny.

The Supreme Court has been under a cloud since Bush v. Gore, when it massively distorted the law in order to install its preferred candidate as president – a president who, it turned out, was one of the most incompetent in American history. Perhaps their rush to take this case is a bid for renewed legitimacy. It’s no great legal feat to say that silly arguments are silly, and on that basis to uphold the ACA. The Court generally occupies itself with hard cases, not easy ones. But this prominent case, which they have made even more prominent by dragging on argument for days, lets it say to all the Gore supporters (and the very large number of Bush supporters with buyers’ remorse) that, see, we’re nonpartisan and legitimate after all. As a legal matter, the answer is obvious, and as a political matter the advantages are delicious. Who could resist?

But all this presumes that they do understand how silly those arguments are. We will get our first hint about the Justices’ thinking on that question when we see what questions they ask Tuesday.