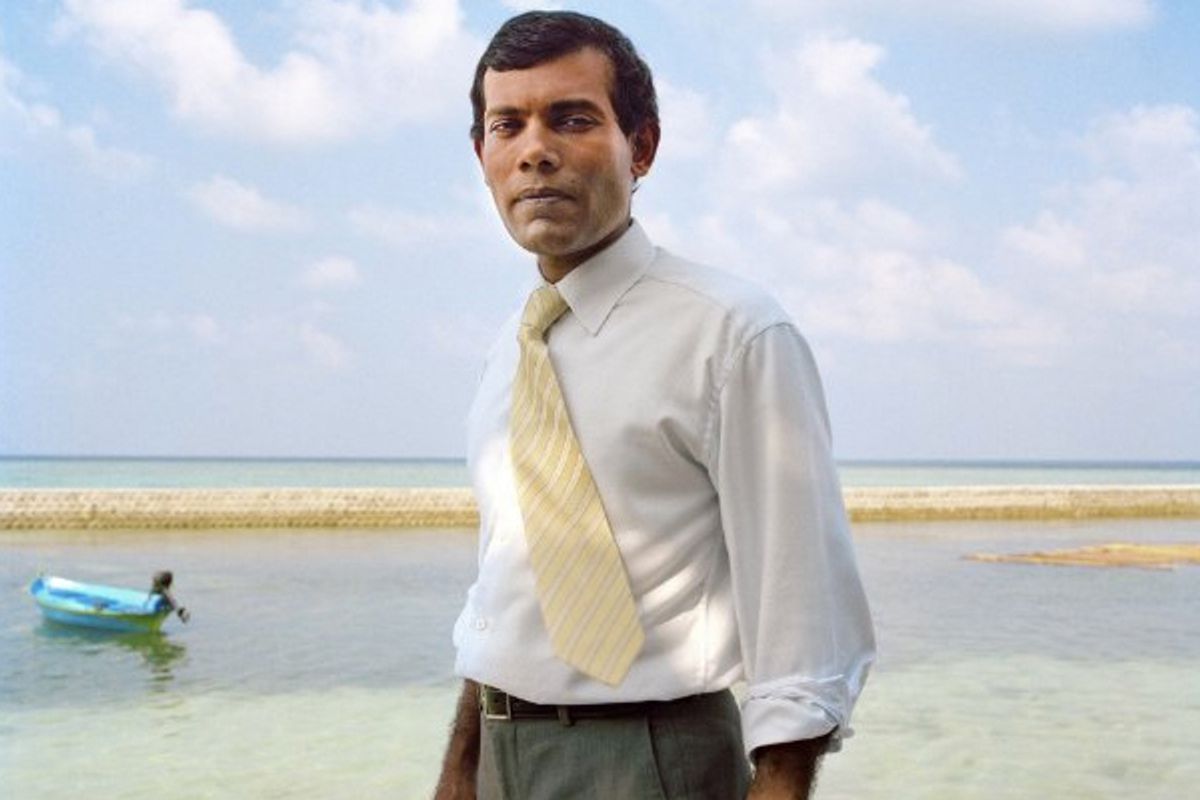

It would be too optimistic to claim that the 2009 Copenhagen Summit represented a breakthrough or turning point in the battle against climate change. But it was the first moment when the United States, China and India -- the world's biggest polluters -- all agreed in principle to reduce carbon emissions, and as symbolic statements go, that one was pretty big. Copenhagen also catapulted a most unlikely head of state to pop-star status, at least within the worldwide environmental movement. Mohamed Nasheed, who was then the president of the Maldives -- Asia's smallest country, both in area and population -- emerged as the developing world's most charismatic and dynamic spokesman on the causes, and the costs, of global warming.

A British-educated democratic activist who had been tortured in prison during the 30-year dictatorship of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, Nasheed was the surprise winner of a 2008 election that followed a popular uprising against the regime. In addition to pursuing an ambitious agenda of liberalization and modernization within his entirely Islamic nation, Nasheed seized upon climate change as an international clarion call. And no wonder -- the Maldives is an Indian Ocean archipelago of several hundred inhabited islands (and fewer than 350,000 people), with a median altitude of 1.5 meters above sea level. As Nasheed says in Jon Shenk's extraordinarily compelling documentary film, "The Island President," it is a nation without a single hill. Nasheed has traveled the world describing the Maldives as the Poland of global warming -- meaning, of course, Poland in 1939. If his country cannot be saved from rising sea levels, he maintains, then there may be no saving Tokyo or Mumbai or New Orleans or New York.

Shenk got extraordinary access to the inner workings of Nasheed's administration, attending cabinet meetings in Malé, the Maldivian capital, and traveling with Nasheed to address the British Parliament and the United Nations. We watch Nasheed and his advisors hatching the plan to make the Maldives the world's first carbon-neutral nation -- not because it will make any practical difference, but because it will stand as a moral example that might shame the big emitters into doing something. ("At least we will die knowing we did the right thing," he says.) Most fascinating of all, we observe the backroom deal that Nasheed helped broker in Copenhagen, where he served as a critical emissary between his Western allies (notably the British and Australian prime ministers) and the Chinese and Indian delegations, which viewed any climate deal as an unfair limitation on their right to self-development.

"The Island President" had been playing at film festivals for more than a year, to widespread acclaim, when an unexpected political twist lent it a new urgency. In early February, Nasheed was forced to resign the presidency in what he says was a coup d'état staged by Gayoom and his supporters, including radical Islamists who opposed his reforms. As Nasheed wrote in a New York Times Op-Ed a day after his resignation, "Let the Maldives be a lesson for aspiring democrats everywhere: the dictator can be removed in a day, but it can take years to stamp out the lingering remnants of his dictatorship."

I recently met with Nasheed and filmmaker Jon Shenk, at a private club in downtown Manhattan to discuss "The Island President," climate change policy and the situation in the Maldives. If the public genuinely supported him, I asked the former president, couldn't he have resisted the coup. "Yes, I could have remained in power," he said. "We could have murdered the coup. I could have asked people to go out and start shooting at the police, and finish it. But that would be a very shortsighted way of looking at things." One can perhaps accuse Nasheed of being too idealistic, or overly optimistic -- I'm afraid he undervalues the power of know-nothingism, arrogance and stupidity in American politics, for example. But you can't say he isn't taking the long view. (He says that if and when new elections are held in the Maldives, he will definitely run again.)

Mr. President, early in the film there's a scene where you observe that after you had taken power in 2008 you thought the fight was over, and then you realized it was only beginning. That's even more prophetic now than it was then.

Mohamed Nasheed: Yes, it is. You know, the dictatorship is back again. We were complacent to think that it would be easy to get rid of a dictatorship. Of course it was not easy to win that election and bring Gayoom down in the first place. But now he is back again, and the fight has to continue. It is very important that democracy be restored in the Maldives, and we hope that friendly governments understand the necessity and the need for it. As we see it now, I'm afraid the government there is going to all sorts of places. Certainly it's not going democratically, and we need to bring it back.

For people who might not have followed the confusing news reports out of your country, please update us on what's been going on.

There was a coup, and they overthrew the elected government. The previous dictator, Gayoom, is back, and all his children are back in ministerial posts. All his associates are back in government. Also, what is worse -- not only Gayoom is back, but this coup was instigated through Islamic radicalism as well. There is a section of that in the Maldives, and I'm afraid we now have three Islamic radicals in the cabinet. We beat them in three elections, and they were not able to get any position in government. Now, through the coup, they are back, and Gayoom is back. So there is no respect for what the people have said.

And how has the general public reacted to this?

Everyone is out on the streets. There are huge demonstrations going on. People don't seem to be getting tired. They're not relenting, and they want to go on and on and on. We hope for a peaceful solution, of course, to what is happening now. We wouldn't want the country to deteriorate into violence. If we can act quickly, if we can do it now, we will be avoiding a whole bunch of difficulties in the future.

President Obama spent part of his childhood in the Indian Ocean region and has a long-standing personal and political interest in that part of the world. Has he or his administration reached out to you since the coup?

I'm afraid that the United States government was very quick to recognize the status quo. This is very, very sad. I was shocked to see that. I hoped that they would understand, and realign their policies. Now I'm trying to speak to the people of the United States, because of that. We respect the United States and its people so much. We've been trying to liberalize the country. We've been trying to make it into a more moderate country, and it is sad that our policies were not seen and not backed by the United States. They're still talking about how they need time; they're still talking to Gayoom. There's a game we used to play when we were little: Finders Keepers. It doesn't matter how you find it, you know! But that's not how one would support a democracy. I would hope that President Obama would understand what is happening in the Maldives, and I would hope he would lay his weight on the bureaucrats and bring a better political solution to what is happening in our country.

I assume that the new government, the one headed by your former vice president, is not going to address the climate-change issue in the same way you did.

They can't. You must have a high moral authority to address climate change. Every time you start speaking, you know, you can't be answering back to the skeletons in your own closet. So it's not going to be possible for them to articulate in the same manner as a democratic government. I don't see it happening.

At numerous points in the film, you express personal misgivings about dealing with the compromises and the rhetoric of politics. It makes the film very dramatic, because you seem like such a plainspoken and pragmatic person in a realm of spin and empty words. How frustrating was it, actually being a head of state?

Well, you know, soon you realize this is how governments work. We were elected to show our differences, not to go along with the status quo or to go along with tradition. We were elected to change things, so we did change things. We brought in legislation for a proper tax system. We brought in legislation for social protection programs, including medical care for all. We wanted to liberalize the country, in tune with its older Islamic traditions. We wanted to bring out the women, to empower them. These were all things that we were facing, major challenges. We wanted to reform the judiciary, the military, the police. We could not address all these things, and yes, at times it was frustrating. But we were, I think, delivering on our pledges and that was why Gayoom came back. He knew he could do nothing in elections, so he had to topple me.

Jon, let's bring you into the conversation. As an outsider who clearly spent a lot of time in the Maldives, did you see the writing on the wall, as far as what happened to Nasheed's presidency?

Jon Shenk: Anybody visiting the capital or talking to people in government could see from the get-go that the shadow of 30 years of dictatorship loomed heavily over the country. You're talking about 30 years of autocratic rule, where contracts were given to favored relatives and friends, monopolies were allowed and all that. We would go to cafés in the capital and sit with our Maldivian counterparts to talk about the logistics of filmmaking, and their answers would be given to us in whispers. We'd ask, "Why are you whispering?" and they would say, "Well, you never know who's in the room. Gayoom's people could be in the room." That's the kind of fear they had. I'd say, "But they're not in power anymore," and the answer was, "Oh, but they are. They're still in the police, they run the opposition parties, they're trying to undermine us at every stage. And if they do get the presidency back, we'll be put in prison."

So that kind of fear really did exist. When the coup happened, it was shocking, and I was worried about Nasheed and others who I'd been working with. But it wasn't surprising. They really were trying to do an impossible thing in the Maldives, by creating this vision of a modern, liberal, democratic state on the shoulders of years and years of despotism. And by the way, think about what's going on in Egypt and Tunisia and Libya today. That's what they're trying to do, and in some ways what we're seeing here -- two steps forward, one step back -- could be a harbinger of what is to come in those countries.

Mr. President, you've mentioned the role that Islamic radicals now play in the government. Can you talk about the role that Islam has played historically in the Maldives?

M.N.: Whatever happens in the Middle East also happens in the Maldives, and whatever happens in the Maldives also happens in the Middle East. During the '70s, Wahhabism and radical Islam, as soon as it started elsewhere, filtered into the Maldives. And then we saw Gayoom coming. He was educated at al-Azhar University [in Egypt], where he was a classmate of Hosni Mubarak. Gayoom came in the late '70s, and that also fueled the Islamic rhetoric. When he discovered he could no longer control the radicals, he started arresting them and beating them up. That created an underground network of Islamic radicals, and for a long time they were the only organized group in town. The only organized dissent came from them, because [the democratic opposition] were all in jail.

So young people started joining the radical Islamic groups, and by the time we were able to articulate a movement, they were already entrenched. But we were able to beat them in elections, over and over again. We beat them in the presidential election and we beat them in the parliamentary elections. Out of 1,081 local council seats, they won 4, and only because we did not want to contest them there. I felt that they had to be in the game somewhere. My assumption and my feeling is, you know, if we were able to do the things we were working on, without the coup, we would have been able to liberalize the country and address Islamic radicalism through democratic means, without infringing on their human rights and so on. But unfortunately we were not allowed to do that.

So what is the ideology driving Gayoom and his supporters? Or is there any?

No, there's no ideology behind it. I mean, the ideology is xenophobia and racism. All the rhetoric against Israel and the West, calling everyone a heathen. It's really narrow-minded and intolerant and nationalistic. This is an island mentality as well, but it's possible to change that. It's not the people who have that mentality but the ruling elite, who want to suppress the people through that narrative, that rhetoric.

Jon, this movie has now gotten a lot of publicity that perhaps you did not expect. Is there a danger that the issue you set out to highlight -- the importance of climate change, and of President Nasheed's engagement with the issue -- is now being overshadowed by the political context?

J.S.: When you asked earlier whether the new government would carry on the climate battle, the thing is that Waheed, the new president and former vice president, might pay lip service to that. But it totally ignores the important thing that has happened in the Maldives, where Nasheed and his people have been working for 20 years, in a grass-roots, Gandhian struggle for civil rights and good governance and freedom of speech, all that stuff that has happened in so many of the great democracies of the world. The fight against climate change is an extension of that, in President Nasheed's mind. It's a fight for human rights. It's a fight for the right to exist in a healthy environment and to have the freedom that goes along with that. So they're one and the same. The fact that the film might get a little more publicity because of this political struggle really is one and the same with the struggle on climate change. It sounds naïve, maybe, but you're struggling for truth and justice. The climate debate is about that, and so is the fight for democracy. Thematically they are the same, and that's why Nasheed took on the climate fight when he stepped into office. It was an extension of his life's work.

M.N.: During the '70s, democracy movements had human rights as a foundation to build on. I feel that now climate issues and human rights are equally important. You have to save the planet as much as save the people, and democracy can be built on that foundation. I would hope that Egyptians, or all the other democracy movements in the Middle East, would find climate change as a track that they have to address. They cannot come into government without understanding climate issues, and what is happening to the environment around them. If you get beaten up as a human being, that's very bad. When the world gets battered, no one is physically crying, but the planet is. All democracy leaders, all people who want to fight for freedom and justice, must fight for climate as well. In that sense, Jon's film is timely and necessary. It's must viewing for anybody with any interest in democracy.

How long do we have to save the Maldives? If nothing is done, when will your country become uninhabitable?

I think the science here is very, very sorted out. We can't be so silly as to question the science. We have a window of about seven years to start acting now, and if we can't do that, then I think within the next 70 years or so we will have very serious issues, not just in the Maldives but everywhere. Issues about resources, about water, about migration. Climate migration -- there will be a huge exodus of people from place to place. The Pentagon has come out and said that this is a huge national security threat. But elections are fought almost entirely on economic issues. Nobody talks about human rights.

Presumably we're not going to hear either President Obama or Gov. Romney talking about this issue for the rest of the year. They may talk about gasoline prices, but not about the underlying issues.

No, but the thing is, we do everything that we do for our children. Why are you working? Why am I working? We would not have any policies for ourselves, but we should have policies for our children. I think democratic leaders have been so shortsighted in listening to their advisors: "Oh, no, no, there are huge oil companies who can do this and that. You can't do this, Mr. President!" You can do it, and you have to do it. You might lose power, but you are saving your children. We can't have our policies only go as far as their noses, and the next election.

I am sure a new age of politicians is coming, in the United States as well. I still believe that if President Obama would start articulating on climate issues, he would get more votes, not fewer. I am convinced of it. The people of this country -- yes, you are worried about gasoline prices, that's true. But you are also worried about what's happening to the rest of the world, to your own planet. You can't just assume people are so simple, and be so condescending toward them. If you listen to advisors, the only thing people care about, apparently, is what's in their pocket. If that were true, I wouldn't be in government. Our children understand all this better than we do. They are not going to vote for oil companies and the status quo. If political leaders think that they have a future by taking the safe side, I think they're very wrong.

"The Island President" is now playing in New York and San Francisco. It opens April 6 in Los Angeles; April 18 in Waterville, Maine; April 20 in San Diego and Washington; and April 27 in Detroit and Minneapolis, with more cities to follow.

Shares