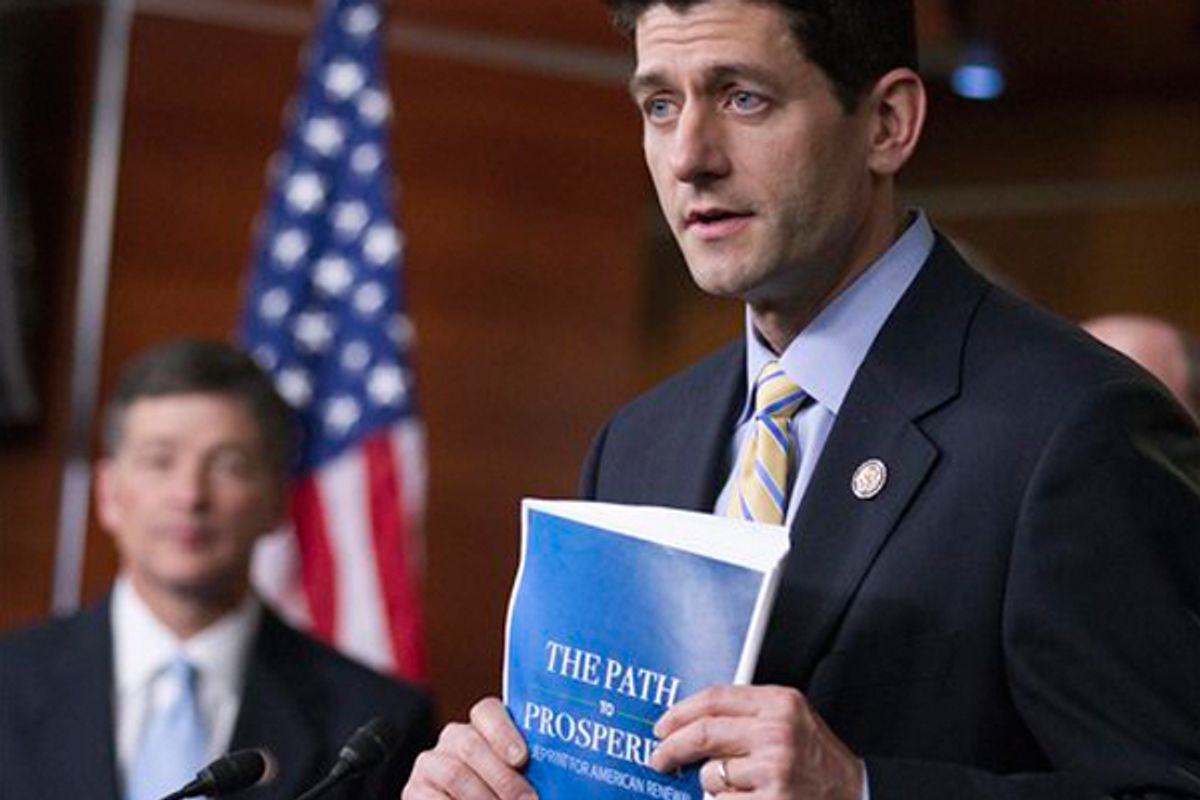

The Paul Ryan-authored budget approved by the House on Thursday has zero chance of being enacted, thanks to Democratic control of the Senate and White House. But there is a 100 percent chance that it will feature prominently in Democratic campaign ads and talking points from now through the November election.

This is a potential problem for Republicans, since a major component of the plan is a radical overhaul of Medicare, one of the most popular government programs. Ryan’s budget also calls for steep tax reductions that would disproportionately benefit the affluent and would potentially cut deeply into the social safety net. Just like the Medicare voucher plan that Ryan proposed and House Republicans lined up behind last year, it is a document that Democrats are itching to run against this fall, and to which they hope to tie every Republican candidate.

Republicans, obviously, are well aware of this. Many of them don’t care. They either adamantly believe that Ryan’s plans are in the country’s best interest, or they don’t have to worry because they represent Republican-dominated constituencies (or both). Others are probably more conflicted, fearful of the ammunition they’re handing Democrats but just as scared – or more scared – of being labeled a RINO in the Obama/Tea Party-era. The ghosts of Bob Bennett and Bob Inglis haunt Republicans on Capitol Hill.

This helps explains why John Boehner, who claimed the speaker’s gavel after the 2010 elections because he was in line for it, and not because of any great affection from Tea Party conservatives, was willing to bring Ryan’s Medicare plan for a vote last year, and why just about every Republican in the House voted for it – just as nearly every House Republican voted for Ryan’s budget this week. And it helps explain why Mitt Romney, who has no choice but to appease skeptical conservatives on every litmus test issue, has been so intent on winning Ryan’s endorsement (which he finally did today) and will defend his program as the Republican nominee.

There is, though, a tiny batch of Republican lawmakers who feel that the Ryan budget is too politically toxic. The group is smaller than 10, the number of House Republicans who voted against it this week. Most of those “no” votes came from staunchly conservative members who represent deeply red districts and who apparently believe that Ryan’s budget isn’t conservative enough. For instance, Justin Amash, a freshman from a Western Michigan district who has impeccable Tea Party credentials, told his local newspaper that Ryan’s plan doesn’t cut enough spending and takes too long to balance the budget. Six of the 10 GOP “no” votes seem to fit this criteria.

That leaves four members who apparently have different concerns. One of them, Pennsylvania’s Todd Platts, who some consider the least conservative Republican in the House, is retiring this year, so general election considerations clearly weren’t on his mind. But the other three all have reason to worry about November: New York’s Chris Gibson, a freshman who (thanks to redistricting) will run this fall in a district that gave Barack Obama 53 percent in 2008; David McKinley, who won his West Virginia seat by less than a point in 2010; and Denny Rehberg, the at-large congressman from Montana who is now locked in one of the most hotly contested Senate races in the country, against Democrat Jon Tester.

All three of them have very obvious reasons to fear the taint of the Ryan budget. The question is whether voting against it will do much to protect them from Democratic attacks. Since this week’s vote (and last year’s) both essentially split on party lines and since Romney seems poised to defend it this fall, it may not be hard for Democrats to make the Ryan budget/Medicare plan synonymous with the Republican Party. If that happens, voters may end up oblivious to the “no” votes of Rehberg, McKinley and Gibson and punish them simply because of their party label.

In a way, this calls to mind the impact of healthcare reform on the 2010 midterms. Many panicky Democrats in vulnerable districts voted against the law, terrified of the political consequences. There’s some evidence that this didn’t do them any good; 22 of the 34 Democrats who voted “no” ended up losing their seats anyway, many of them by wide margins. Then again, as an analysis from Smart Politics found, of the 23 Democrats who voted against healthcare and represented districts that supported John McCain in 2008, nine were reelected; of the 18 from McCain districts who voted for healthcare, just two won reelection.

Shares