America emerged from the Great Depression and the Second World War with a much more equal distribution of income than it had in the 1920s; our society became middle-class in a way it hadn’t been before. This new, more equal society persisted for 30 years. But then we began pulling apart, with huge income gains for those with already high incomes. As the Congressional Budget Office has documented, the 1 percent — the group implicitly singled out in the slogan “We are the 99 percent” — saw its real income nearly quadruple between 1979 and 2007, dwarfing the very modest gains of ordinary Americans. Other evidence shows that within the 1 percent, the richest 0.1 percent and the richest 0.01 percent saw even larger gains.

By 2007, America was about as unequal as it had been on the eve of the Great Depression — and sure enough, just after hitting this milestone, we plunged into the worst slump since the Depression. This probably wasn’t a coincidence, although economists are still working on trying to understand the linkages between inequality and vulnerability to economic crisis.

Here, however, we want to focus on a different question: Why has the response to the crisis been so inadequate? Before financial crisis struck, we think it’s fair to say that most economists imagined that even if such a crisis were to happen, there would be a quick and effective policy response. In 2003 Robert Lucas, the Nobel laureate and then-president of the American Economic Association, urged the profession to turn its attention away from recessions to issues of longer-term growth. Why? Because, he declared, the “central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.”

Yet when a real depression arrived — and what we are experiencing is indeed a depression, although not as bad as the Great Depression — policy failed to rise to the occasion. Yes, the banking system was bailed out. But job-creation efforts were grossly inadequate from the start — and far from responding to the predictable failure of the initial stimulus to produce a dramatic turnaround with further action, our political system turned its back on the unemployed. Between bitterly divisive politics that blocked just about every initiative from President Obama, and a bizarre shift of focus away from unemployment to budget deficits despite record-low borrowing costs, we have ended up repeating many of the mistakes that perpetuated the Great Depression.

Nor, by the way, were economists much help. Instead of offering a clear consensus, they produced a cacophony of views, with many conservative economists, in our view, allowing their political allegiance to dominate their professional competence. Distinguished economists made arguments against effective action that were evident nonsense to anyone who had taken Econ 101 and understood it. Among those behaving badly, by the way, was none other than Robert Lucas, the same economist who had declared just a few years before that the problem of preventing depressions was solved.

So how did we end up in this state? How did America become a nation that could not rise to the biggest economic challenge in three generations, a nation in which scorched-earth politics and politicized economics created policy paralysis?

We suggest it was the inequality that did it. Soaring inequality is at the root of our polarized politics, which made us unable to act together in the face of crisis. And because rising incomes at the top have also brought rising power to the wealthiest, our nation’s intellectual life has been warped, with too many economists co-opted into defending economic doctrines that were convenient for the wealthy despite being indefensible on logical and empirical grounds.

Let’s talk first about the link between inequality and polarization.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Our understanding of American political economy has been strongly influenced by the work of the political scientists Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal and Nolan McCarty. Poole, Rosenthal and McCarty use congressional roll-call votes to produce a sort of “map” of political positions, in which both individual bills and individual politicians are assigned locations in an abstract issues space. The details are a bit complex, but the bottom line is that American politics is pretty much one-dimensional: Once you’ve determined where a politician lies on a left-right spectrum, you can predict his or her votes with a high degree of accuracy. You can also see how far apart the two parties’ members are on the left-right spectrum — that is, how polarized congressional politics is.

It’s not surprising that the parties have moved ever further apart since the 1970s. There used to be substantial overlap: There were moderate and even liberal Republicans, like New York’s Jacob Javits, and there were conservative Democrats. Today the parties are totally disjointed, with the most conservative Democrat to the left of the most liberal Republican, and the two parties’ centers of gravity very far apart.

What’s more surprising is the fact that the relatively nonpolarized politics of the post-war generation is a relatively recent phenomenon — before the war, and especially before the Great Depression, politics was almost as polarized as it is now. And the track of polarization closely follows the track of income inequality, with the degree of polarization closely correlated over time with the share of total income going to the top 1 percent.

Why does higher inequality seem to produce greater political polarization? Crucially, the widening gap between the parties has reflected Republicans moving right, not Democrats moving left. This pops out of the Poole-Rosenthal-McCarty numbers, but it’s also obvious from the history of various policy proposals. The Obama health care plan, to take an obvious example, was originally a Republican plan, in fact a plan devised by the Heritage Foundation. Now the GOP denounces it as socialism.

The most likely explanation of the relationship between inequality and polarization is that the increased income and wealth of a small minority has, in effect, bought the allegiance of a major political party. Republicans are encouraged and empowered to take positions far to the right of where they were a generation ago, because the financial power of the beneficiaries of their positions both provides an electoral advantage in terms of campaign funding and provides a sort of safety net for individual politicians, who can count on being supported in various ways even if they lose an election.

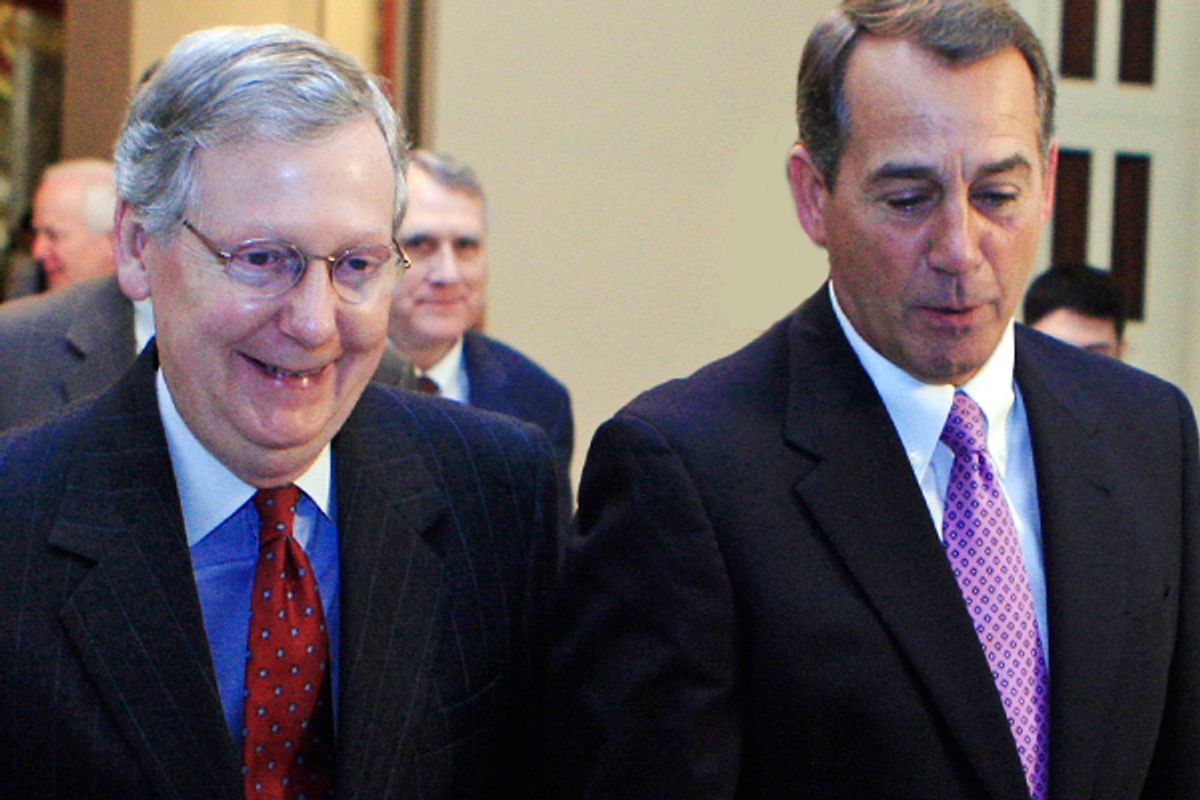

Whatever the precise channels of influence, the result is a political environment in which Mitch McConnell, leading Republican in the Senate, felt it was perfectly okay to declare before the 2010 midterm elections that his main goal, if the GOP won control, would be to incapacitate the president of the United States: “The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.”

Needless to say, this is not an environment conducive to effective anti-depression policy, especially given the way Senate rules allow a cohesive minority to block much action. We know that the Obama administration expected to win strong bipartisan support for its stimulus plan, and that it also believed that it could go back for more if events proved this necessary. In fact, it took desperate maneuvering to get sixty votes even in the first round, and there was no question of getting more later.

In sum, extreme income inequality led to extreme political polarization, and this greatly hampered the policy response to the crisis. Even if we had entered the crisis in a state of intellectual clarity — with major political players at least grasping the nature of the crisis and the real policy options — the intensity of political conflict would have made it hard to mount an effective response.

In reality, of course, we did not enter the crisis in a state of clarity. To a remarkable extent, politicians — and, sad to say, many well-known economists — reacted to the crisis as if the Great Depression had never happened. Leading politicians gave speeches that could have come straight out of the mouth of Herbert Hoover; famous economists reinvented fallacies that one thought had been refuted in the mid-1930s. Why?

The answer, we would suggest, also runs back to inequality.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

It’s clear that the financial crisis of 2008 was made possible in part by the systematic way in which financial regulation had been dismantled over the previous three decades. In retrospect, in fact, the era from the 1970s to 2008 was marked by a series of deregulation-induced crises, including the hugely expensive savings and loan crisis; it’s remarkable that the ideology of deregulation nonetheless went from strength to strength.

It seems likely that this persistence despite repeated disaster had a lot to do with rising inequality, with the causation running in both directions. On one side, the explosive growth of the financial sector was a major source of soaring incomes at the very top of the income distribution. On the other side, the fact that the very rich were the prime beneficiaries of deregulation meant that as this group gained power — simply because of its rising wealth — the push for deregulation intensified.

These impacts of inequality on ideology did not end in 2008. In an important sense, the rightward drift of ideas, both driven by and driving rising income concentration at the top, left us incapacitated in the face of crisis.

In 2008 we suddenly found ourselves living in a Keynesian world — that is, a world that very much had the features John Maynard Keynes focused on in his 1936 magnum opus, "The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money." By that we mean that we found ourselves in a world in which lack of sufficient demand had become the key economic problem, and in which narrow technocratic solutions, like cuts in the Federal Reserve’s interest rate target, were not adequate to that situation. To deal effectively with the crisis, we needed more activist government policies, in the form both of temporary spending to support employment and efforts to reduce the overhang of mortgage debt.

One might think that these solutions could still be considered technocratic, and separated from the broader question of income distribution. Keynes himself described his theory as “moderately conservative in its implications,” consistent with an economy run on the principles of private enterprise. From the beginning, however, political conservatives — and especially those most concerned with defending the position of the wealthy — have fiercely opposed Keynesian ideas.

And we mean fiercely. Although Paul Samuelson’s textbook "Economics: An Introductory Analysis" is widely credited with bringing Keynesian economics to American colleges in the 1940s, it was actually the second entry; a previous book, by the Canadian economist Lorie Tarshis, was effectively blackballed by rightwing opposition, including an organized campaign that successfully induced many universities to drop it. Later, in his "God and Man at Yale," William F. Buckley Jr. would direct much of his ire at the university for allowing the teaching of Keynesian economics.

The tradition continues through the years. In 2005 the right-wing magazine Human Events listed Keynes’s "General Theory" among the 10 most harmful books of the 19th and 20th centuries, right up there with "Mein Kampf" and "Das Kapital."

Why such animus against a book with a “moderately conservative” message? Part of the answer seems to be that even though the government intervention called for by Keynesian economics is modest and targeted, conservatives have always seen it as the thin edge of the wedge: concede that the government can play a useful role in fighting slumps, and the next thing you know we’ll be living under socialism. The rhetorical amalgamation of Keynesianism with central planning and radical redistribution — although explicitly denied by Keynes himself, who declared that “there are valuable human activities which require the motive of money-making and the environment of private wealth-ownership for their full fruition” — is almost universal on the right.

There is also the motive suggested by Keynes’s contemporary Michał Kalecki in a classic 1943 essay:

We shall deal first with the reluctance of the “captains of industry” to accept government intervention in the matter of employment. Every widening of state activity is looked upon by business with suspicion, but the creation of employment by government spending has a special aspect which makes the opposition particularly intense. Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment depends to a great extent on the so-called state of confidence. If this deteriorates, private investment declines, which results in a fall of output and employment (both directly and through the secondary effect of the fall in incomes upon consumption and investment). This gives the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be carefully avoided because it would cause an economic crisis. But once the government learns the trick of increasing employment by its own purchases, this powerful controlling device loses its effectiveness. Hence budget deficits necessary to carry out government intervention must be regarded as perilous. The social function of the doctrine of “sound finance” is to make the level of employment dependent on the state of confidence.

This sounded a bit extreme to us the first time we read it, but it now seems all too plausible. These days you can see the “confidence” argument being deployed all the time. For example, here is how Mort Zuckerman began a 2010 op-ed in the Financial Times, aimed at dissuading President Obama from taking any kind of populist line:

The growing tension between the Obama administration and business is a cause for national concern. The president has lost the confidence of employers, whose worries over taxes and the increased costs of new regulation are holding back investment and growth. The government must appreciate that confidence is an imperative if business is to invest, take risks and put the millions of unemployed back to productive work.

There was and is, in fact, no evidence that “worries over taxes and the increased costs of new regulation” are playing any significant role in holding the economy back. Kalecki’s point, however, was that arguments like this would fall completely flat if there was widespread public acceptance of the notion that Keynesian policies could create jobs. So there is a special animus against direct government job-creation policies, above and beyond the generalized fear that Keynesian ideas might legitimize government intervention in general.

Put these motives together, and you can see why writers and institutions with close ties to the upper tail of the income distribution have been consistently hostile to Keynesian ideas. That has not changed over the 75 years since Keynes wrote the "General Theory." What has changed, however, is the wealth and hence influence of that upper tail. These days, conservatives have moved far to the right even of Milton Friedman, who at least conceded that monetary policy could be an effective tool for stabilizing the economy. Views that were on the political fringe 40 years ago are now part of the received doctrine of one of our two major political parties.

A touchier subject is the extent to which the vested interest of the 1 percent, or better yet the 0.1 percent, has colored the discussion among academic economists. But surely that influence must have been there: if nothing else, the preferences of university donors, the availability of fellowships and lucrative consulting contracts, and so on must have encouraged the profession not just to turn away from Keynesian ideas but to forget much that had been learned in the 1930s and ’40s.

In the debate over responses to the Great Recession and its aftermath, it has been shocking to see so many highly credentialed economists making not just elementary conceptual errors but old elementary conceptual errors — the same errors Keynes took on three generations ago. For example, one thought that nobody in the modern economics profession would repeat the mistakes of the infamous “Treasury view,” under which any increase in government spending necessarily crowds out an equal amount of private spending, no matter what the economic conditions might be. Yet in 2009, exactly that fallacy was expounded by distinguished professors at the University of Chicago.

Again, our point is that the dramatic rise in the incomes of the very affluent left us ill prepared to deal with the current crisis. We arrived at a Keynesian crisis demanding a Keynesian solution — but Keynesian ideas had been driven out of the national discourse, in large part because they were politically inconvenient for the increasingly empowered 1 percent.

In summary, then, the role of rising inequality in creating the economic crisis of 2008 is debatable; it probably did play an important role, if nothing else than by encouraging the financial deregulation that set the stage for crisis. What seems very clear to us, however, is that rising inequality played a central role in causing an ineffective response once crisis hit. Inequality bred a polarized political system, in which the right went all out to block any and all efforts by a modestly liberal president to do something about job creation. And rising inequality also gave rise to what we have called a Dark Age of macroeconomics, in which hard-won insights about how depressions happen and what to do about them were driven out of the national discourse, even in academic circles.

This implies, we believe, that the issue of inequality and the problem of economic recovery are not as separate as a purely economic analysis might suggest. We’re not going to have a good macroeconomic policy again unless inequality, and its distorting effect on policy debate, can be curbed.

From "The Occupy Handbook." Edited by Janet Byrne. On sale April 17, 2012. Excerpted with permission from Little, Brown and Co.

Shares