The news that no Pulitzer Prize for fiction would be awarded this year came like a slap across the face to a book world still reeling from a Department of Justice suit filed against publishers trying to forestall an Amazon e-book monopoly. Double ouch! But does the Pulitzer snub mean that no good fiction was published in America last year?

I would (and have) argued otherwise, most strenuously; 2011 was an exceptional year for fiction, American and otherwise. I also suspect that the Pulitzer Board itself has not turned up its collective nose at every book produced by American novelists and short story writers in 2011. The Pulitzer Prize may wield far more clout with book buyers than any other American prize for fiction. It can turn an obscure title into a success and a modestly successful title into a bestseller. Readers take it seriously and snap up the books it honors by the thousands. But that doesn't mean that the Pulitzer Prize for fiction doesn't suffer from the same problems that afflict every literary prize, no matter its size or influence.

I have some insight into those problems because I served on the Pulitzer fiction jury two years ago. I can't talk about my jury's deliberations, however -- that was part of the deal. I can tell you that choosing the winner of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction is a two-tier process, a fact that even people well-versed in the literary world tend to forget.

The first tier is the jury's selection. Three jurors (usually an academic, a critic and a fiction writer) are responsible for wading through huge boxfuls of books. Anyone can submit his or her book to the Pulitzer competition for a small fee, and believe me: anyone does. We got hundreds and hundreds of them, including many self-published novels with titles like "The Bikinis of Alpha Centauri," most of which read as if they'd been run through Google Translate into Farsi and then run back again into English before being committed to print.

From the many submissions, the jury picks three titles to recommend to the Pulitzer Board, and the board picks the actual winner, as well as selecting the winners of all the other Pulitzer Prizes. The board does have the option to select a title not on the jury's list, but it rarely does so nowadays.

The heyday for picking no book at all was the 1970s, a time of considerable cultural upheaval and conflict. In 1971, the board rejected titles from Eudora Welty, Saul Bellow and Joyce Carol Oates. In 1974, a stellar jury consisting of Benjamin DeMott, Elizabeth Hardwick and Alfred Kazin (three titans of literary criticism) unanimously recommended that the prize go to Thomas Pynchon's "Gravity's Rainbow." The Pulitzer Board dug in its heels and said no. In 1977, the last time the prize was not awarded, the jury favored ''A River Runs Through It'' by Norman Maclean and the board shut them down.

Why? According to the critic and experimental novelist William Gass, who wrote a notorious diatribe on the subject, the Pulitzer Board's taste is hopelessly mainstream, middlebrow and unadventurous. (In 1941, most of the board did pick Ernest Hemingway's "For Whom the Bell Tolls," but one member -- who happened to be the president of Columbia University -- put the kibosh on that because he considered the book immoral.) However, Gass' complaint seems an absurd cavil to level against an institution whose power and influence resides precisely in the fact that it speaks to a broad audience.

The Pulitzer Board consists of working journalists and journalism professors, most with a deep respect for literature but relatively little familiarity with the literary world. This can be a strength and a weakness. The Pulitzer's excellent record at singling out literary works that also appeal to a lot of readers is one reason why it has so much more influence than "insider" prizes like the National Book Award.

However, because the Pulitzer Board is fairly representative of educated Americans, it surely includes a lot of people who don't really have time to read fiction -- or, at least, literary fiction -- anymore. Past boards might have been able to settle on a title that most of them had read even if it wasn't offered as a finalist by the jury; reading at least a few of the "big" novels published during the year was something a lot more people did before the Internet and cable TV came along. In 21st-century America, the novel has become a marginalized and Balkanized art form, and even when avid fiction fans compare notes, they often find they've read nothing in common.

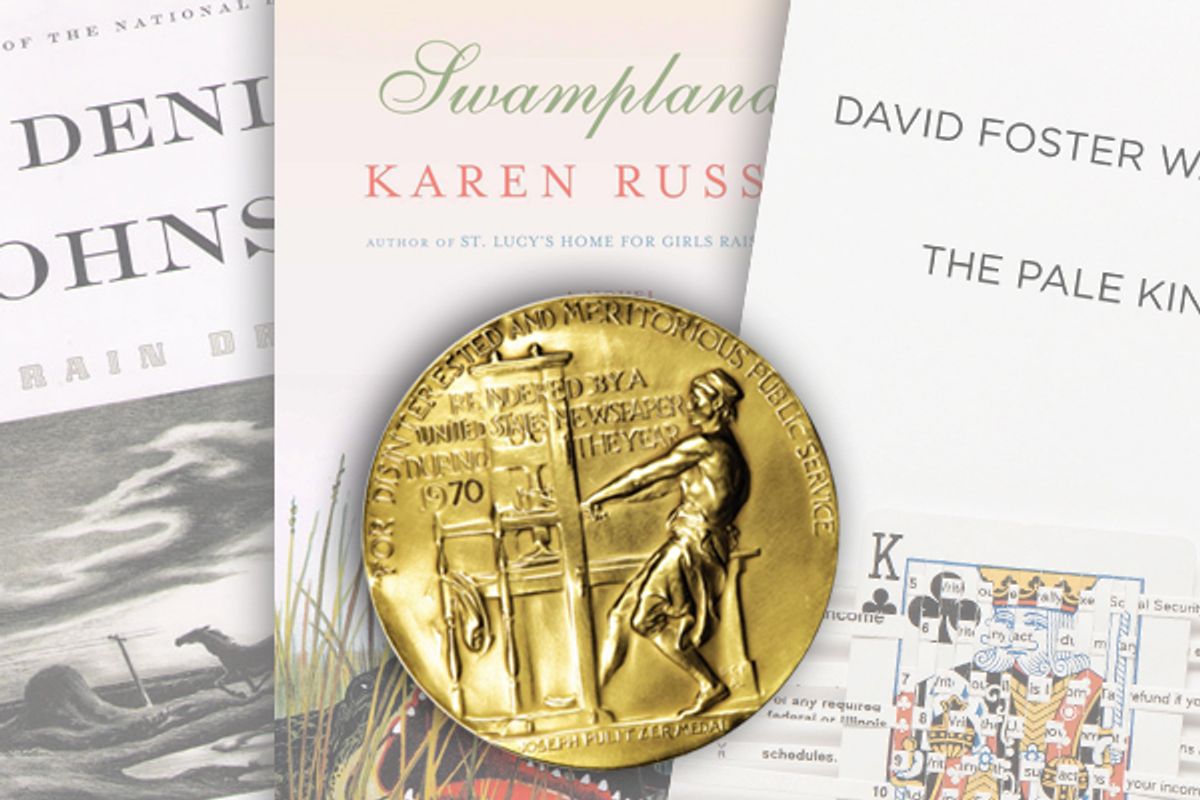

Chances are good that the three novels recommended by this year's Pulitzer jury -- "Swamplandia!" by Karen Russell, "Train Dreams" by Denis Johnson, and "The Pale King" by David Foster Wallace -- are the only three serious new novels many of the board members read last year, apart, perhaps, from one or two others. These people are, after all, pretty busy doing things like editing the Denver Post and running the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, jobs that are a lot more time-consuming than they used to be, as well as selecting the winners in the other Pulitzer categories.

By all accounts, the group could not reach a majority on any of the three titles recommended by the jury. It's certainly unlikely that enough of them read fiction widely enough to agree on an alternate choice. In that, they truly are representative of American readers, and that bodes worse for our national literature than a year without a Pulitzer winner.

Shares