The Republican Party’s standing with the public plunged in the wake of last summer’s debt ceiling standoff and has yet to recover. Just 35 percent of voters, according to a recent poll, have a favorable view of the GOP, while 58 percent have an unfavorable one. By contrast, nearly 50 percent of voters view the Democratic Party favorably.

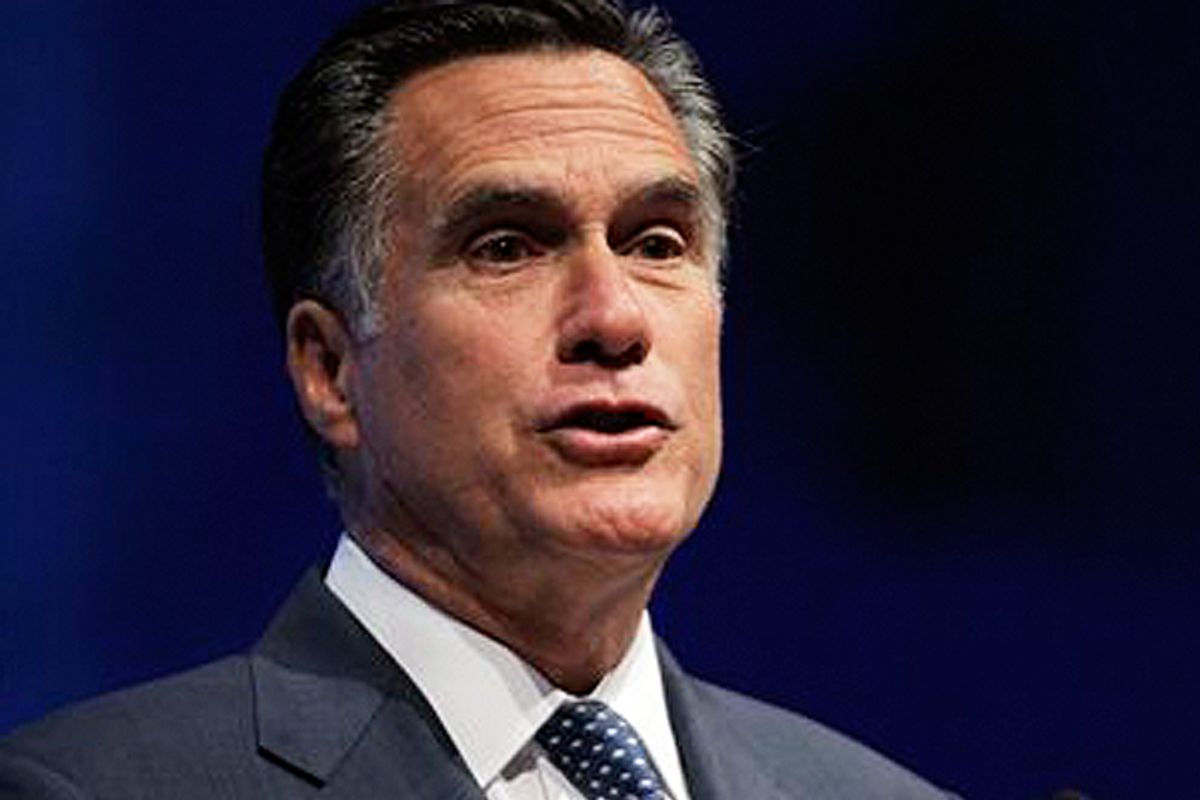

The poisoning of the GOP brand can probably be linked to a few factors, but the compromise-resistant ideological absolutism of the House seems to be the biggest single driver. Thus, the prevailing assumption is that Mitt Romney will at some point stage a dramatic break with House Republicans on some defining issue, a reassuring gesture to swing voters who want to get rid of Barack Obama but who are queasy with the Obama-era GOP’s radicalism.

But, as Jonathan Weisman and Jennifer Steinhauer report in the New York Times today, Republicans in the House are on guard for such a moment and are already making it clear to Romney that “they are driving the policy agenda for the party now.”

This captures the bind in which Romney finds himself. He came to the national stage with a reputation as a moderate, then adjusted his positions until they were in almost perfect alignment with his party’s conservative base. This is why his emergence as the presumptive nominee does not represent a rebuke of Tea Party Republicanism; conservative purists may deeply distrust Romney, but so far as a candidate he’s basically given them everything they wanted. It was enough to secure the nomination for Romney, but it won’t buy him the benefit of the doubt from the right if he now makes any big steps back to the middle.

For example, the Times story quotes Rep. Tim Griffin, a first-term Arkansan with impeccable Tea Party credentials, warning about what would happen if Romney distanced himself from House Republicans on the Paul Ryan budget that Democrats are itching to run against:

“If there was to be a difference of opinion on this, then I think I would make my feelings known,” said Representative Tim Griffin, Mr. Romney’s Arkansas campaign chairman. “I would say, ‘Wait, what are you doing?’ If he says something I disagree with, that’s his right, but I am going to say I disagree.”

The story also draws a parallel to the 2000 campaign, when George W. Bush picked a fight of his own with the House GOP:

In 1999, as House Republicans grappled with far more modest spending cuts, George W. Bush was able to underscore his claim to “compassionate conservatism” by denouncing House efforts. “I don’t think they ought to balance their budget on the backs of the poor,” he said

Sen. Roy Blunt of Missouri, a Republican House leader at the time, recalled that as a “defining moment” for the Bush campaign — one that blindsided Republicans. As Mr. Romney’s designated liaison to congressional Republicans, Mr. Blunt said that one of his jobs was to make sure no one is surprised like that again.

It’s worth considering the Bush example a little more closely. It came as the fiscal year was coming to a close at the end of September ’99, when House Republicans proposed delaying earned income tax credit payments in order to avoid relying on Social Security money to balance the budget. Then, as now, House Republicans were hurting the party’s national image. In the fall of ’99, the GOP’s favorable score was on the upswing (it had cratered at 31 percent during the Clinton impeachment saga of 1998 and early ’99), but it was still nowhere near the Democrats’.

Bush was the overwhelming Republican front-runner at the time, and while it’s true that his remark produced some real outrage from House Republicans, he was never in danger of facing a true revolt from the right. In fact, days after his “backs of the poor” comment, he delivered a speech in which he distanced himself even more from the perceived ideological excesses of the House:

"Too often, on social issues, my party has painted an image of America slouching toward Gomorrah," Mr. Bush said in that speech. "Too often, my party has focused on the national economy, to the exclusion of all else -- speaking a sterile language of rates and numbers. Too often, my party has confused the need for limited Government with a disdain for Government itself."

Bush was allowed by his party to get away with this kind of talk throughout the 2000 campaign. Sure, his primary season opponents played it up and some conservative leaders raised hell too, but Bush came to the race with broad support from many of the right’s most influential figures.

This represents a key difference between where the party was in 2000 and where it is today. Bush's “compassionate conservatism” was the product of the GOP’s futility in battling Clinton. After swamping him in the 1994 midterms, Republicans watched in horror as Clinton regained his popularity by portraying the GOP Congress as a band of ideological extremists bent on destroying the country’s social safety net. Over and over, he beat them soundly -- the 1995 government shutdown, the 1996 election, the ‘98/’99 impeachment ordeal.

For conservatives, the basic appeal of Bush was that he’d be their own Clinton – someone with similar charm and charisma who’d finally be able to deflect the Democratic attacks. They didn’t want him straying too far ideologically, but they were more than happy to give him a lot of room to roam.

Today’s conservatives aren’t looking for another Clinton. They haven’t faced a humbling defeat at Obama’s hands (not yet, at least), and they believe adamantly that rigid adherence to their ideology is a winning national strategy. This doesn’t mean Romney won’t try to distance himself, but if he does, he’ll face a much fiercer backlash than Bush ever did.

Shares