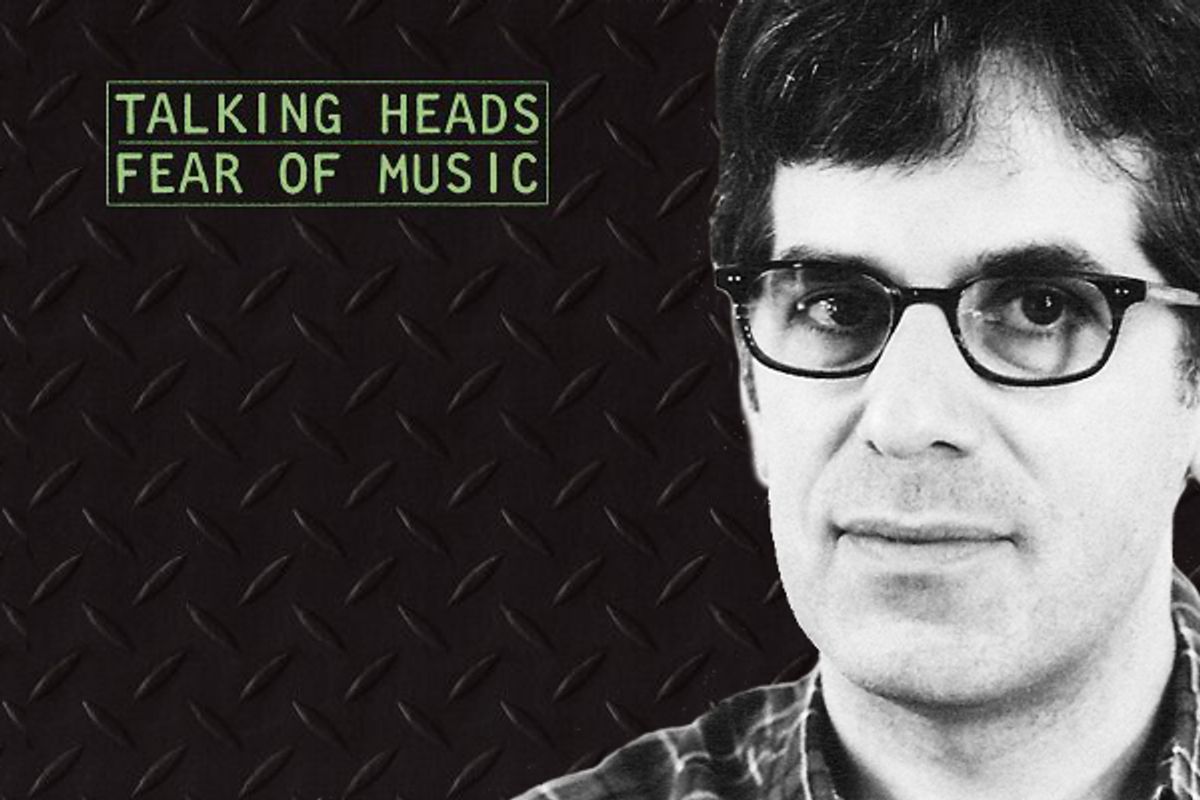

In essay collections like "The Disappointment Artist" and last year's acclaimed "The Ecstasy of Influence," best-selling novelist Jonathan Lethem brought his sharp critical lens and personal passion to bear on Marvel Comics, Roberto Bolaño, Bob Dylan and the John Carpenter movie "They Live." Add to that diverse list of cultural artifacts the Talking Heads album "Fear of Music," the subject of Lethem's latest book, and published as part of Continuum's 33 1/3 series of music writing.

The collision of Lethem and Talking Heads makes perfect sense. Both can't escape being identified with New York – or, in Lethem's case, Brooklyn – and despite working in disparate modes, each brings the formalism and precision of the high arts to popular forms. Lethem fans already know of his love of the band – composed of David Byrne (vocals and guitar), Tina Weymouth (bass), Chris Frantz (drums) and Jerry Harrison (keyboards, guitar) -- from his essay “The Beards.” There, he connected his love of "Fear of Music" to the aftermath of his mother's death from a brain tumor. “I have an obvious predisposition to handling the material of 1978 and '79 with an exaggerated, personal intensity,” he told me. We spoke via Skype, Lethem from his office at Pomona College where he is the Roy E. Disney Professor in Creative Writing.

What drew you to Talking Heads' music as a youth?

In 1978 I launched myself out of a very difficult Brooklyn public school and got into the High School of Music and Art, in Manhattan. It was like crossing the threshold. Suddenly I was hanging out in Harlem, trying to figure out who the cool kids were and how I could become one of them, or whether I somehow already qualified. Everyone had their band; it was pretty much like a menu: You could be into the Ramones or Cheap Trick or the Dictators. U.K. punk was this attractive signal coming in, but we had a special affinity for the New York bands. I had a friend that semester who was into Television — he was a little hipper than I was.

I was just at the right conjugation of nerdy, alienated and hyper-alert that I identified instantly with Talking Heads. They sang songs about books! I got it immediately.

In the book you call "Fear of Music" a paranoid album, and other works of art you've written about – some Stanley Kubrick films, and Philip K. Dick's novels, for instance – have this bent as well. Are you a paranoid person?

Paranoia is closely related to a subject that's right at the heart of the album: fear. Paranoia is an intellectual shading on a somatic experience, a physical reality that is fear. I experienced a lot of fear — not only my mother's death, but I lived through a rather desperate chapter of New York's urban history —and it shaped me. Paranoia is a kind of utilization of fear, like “Let's pick this fear up and shine it around like a flashlight and see what I can see with it.” As it invests itself in certain kinds of artworks, like in Philip K. Dick's novels, paranoia tends to be a mode of inquiry and exploration — a philosophical mode, really. In that sense, it was attractive to me, because it was a lot less passive than just lying there and trembling.

But I try to disentwine my inclination for conspiracy and paranoia in artwork from its general lack of not only usefulness but interest in everyday life, where it's actually a way of shutting possibilities down.

Do you have a favorite song on "Fear of Music"? From your description of “Heaven” – “If heaven's impossible to know, 'Heaven's' hard to recollect” – that seems to be your least favorite.

I received, in a very specific way, skepticism about “Heaven.” I have a friend, John Hilgart, who was a sounding board while I worked on this book. Hilgart said, quite passingly, “I always felt on Side 2, after 'Air,' there's a three-song lull. I like 'Heaven' in principle, but to listen to it is kind of boring.” And then he felt, and I think this would be a much more common remark, that “Animals” and “Electric Guitar” are buried on Side 2 because they're less inspired melodically or fully realized, and bear less relistening.

I had always held the whole album on this pedestal, where, in a way, it was all exactly as good as itself. I saw it as fractal, "This album is perfect, therefore everything on it is perfect.” Besides, I had always taken “Heaven” as a sacred object — everyone knows this is one of the masterpiece songs. But when Hilgart said that it was like – click! – “Heaven” is one of those things that I listen to and tell myself I'm loving it, but it's actually boring. I started focusing on the idea of tedium, because the song's self-referential; it wants to be boring.

In fact, I like “Heaven” a lot. The only song I'm uncomfortable with is “Electric Guitar.” The song is crippled by its disorganized quality, and it doesn't seem as pure conceptually, because how do you put an electric guitar up there with air, heaven, animals, mind? It doesn't belong on that stage. Also, it's been played live barely ever. It's a sitting duck if you need there to be a worst song on the album, though, really, I don't know if "Fear of Music" needs to have one.

I do know that my favorites are the two side closers. I wouldn't want to have to choose between “Drugs” and “Memories Can't Wait.” Those became the most rewarding songs to write about; they just got richer and richer for me. I actually made myself like them even more, which I didn't think was possible. Of course, “Life During Wartime” is pretty good too. [laughs]

Did you find yourself liking the album more in general as a result of writing about it?

It was like having any subject before you when you're writing a book — your own characters, your childhood, some stupid idea you made up about Tourette's syndrome, whatever it might be that you've committed years of your life to — you love it and hate it a lot along the way. There were days when I felt utterly under its hobnailed boot, and there were days when I did not want to listen to "Fear of Music" again. I wrote through those feelings, of course, as you do with your contempt for all the different assignments life has given you, and I was enraptured by the end.

What's weird is that I put it on for pleasure now. Your iTunes counts listenings, and my entire top 25 most-listened-to tracks on iTunes is all "Fear of Music" and different live versions of the songs. It was ceaseless, to the point where my wife would force me to switch to the headphones.

How did you start?

I rarely delay — and certainly proportionate to how many pages the piece was, I don't think I've ever delayed starting a project as long. There are novels that I had in mind for three or four years, or even more than that before I began writing them, but those were very long novels. I took three years circling around this.

I kick-started myself in a really specific way. I accepted an invitation to the Experience Music Project Conference to be on a panel about urbanism. I said I would talk about Talking Heads’ relationship to urbanism and the evolution of their vanity as urban dwellers, starting with the "More Songs About Buildings and Food" song “Big Country,” which goes “I wouldn't live there if you paid me,” to "Fear of Music's" “Cities,” “I'm finding a city I'm going to check out,” and ending with "True Stories'" “People Like Us,” where they're pretending to be hicks from Texas. I saw this as a topic I could make an interesting presentation on, but of course I was thinking, I'll start writing about “Cities” and then I'll have myself on the page about "Fear of Music."

There are small traces of that presentation in the chapter on “Cities” in the book. A lot of it had to get thrown out, but at least it got me thinking about how to make something actually occur. I knew that I would write about each song directly and that I wanted to intersperse those chapters with provocative side questions about the album as a whole — I had that structure sitting there. I wrote about the commercial, the radio spot advertising "Fear of Music," and then I wrote about the album jacket, and then I started writing about “I Zimbra.” Except that I had this weird chunk of thinking about “Cities,” which I incorporated, I wrote the book straight through as it reads.

Were there critical works or other texts that influenced your approach?

I was very conscious of the 33 1/3 books. I've been an eager customer, so I was thinking of some of the ones I loved best, like Franklin Bruno's "Armed Forces," Douglas Wolk's James Brown book, "Live at the Apollo," and Carl Wilson's book on Celine Dion, "Let's Talk About Love." Not that I was going to ape their approaches, which are quite divergent anyway, but I write to enter into a conversation that books on shelves are having. I wanted to be a really exciting member of the 33 1/3 team, I wanted to come in with something that only I could do, but that also was recognizably a contribution to this recent but very interesting tradition.

In terms of critical writing, I followed less a specific example and more the general idea of close reading. I had written a book on the John Carpenter movie "They Live," where I had just stared at the movie and free-associated. I wanted to do that but more so. "They Live" had a relatively high number of outside comparative texts brought in — other films, artworks and some theoretical things. With "Fear of Music" I thought, let me bring in fewer, and let me sometimes bring in none at all, let me just be with the sound of the songs and say what I'm hearing.

You write that it's never unimportant asking what was going on in the artist's life at the moment of creation. Let me turn that on you. Why write this book now?

How can I reconstruct or account for such a sprawling intention? I began fantasizing that I might do a 33 1/3 book before I had even agreed to do one, and "Fear of Music" was always the record that I knew I would write about. Then three years elapsed between agreeing to do it and actually starting.

I have been amazed to find myself doing so much critical and cultural writing, a lot of it being a weird mix of criticism and memoir, or covert memoir pieces pretending to be critical pieces. There's a long evolution for me, thinking I would write fiction that was all going to be invented, and that I like to read criticism but I would never want to write it, then having it invest in the fiction itself. "Fortress of Solitude" is where that really starts, but "Chronic City" extends it. I incorporated a lot of critical impulses, cultural commentary — even things like liner notes crept into the voice of the book.

Having come into this hyper-developed critical voice without ever meaning to, I wanted to both do it service and quarantine it by writing this book. Like, you go over here and write a whole book about "Fear of Music," then shut up. This and the "They Live" book would be both a summit and a farewell, which has to do with an intention for what I want to have happen in my fiction next, which is that I want to stop incorporating the critical voice into it in the same way.

Simultaneously, I think I'm also done with the tokens of my 14- or 15-year-old self. I can't really imagine anything after this climax of "Fear of Music." It's like I finally came out of hiding, like once you show yourself you can slam the door, because the internal paparazzi are satisfied, they got their shot.

In the liner notes of "Sand in the Vaseline," Jerry Harrison said, “There is a shared sensibility [with Talking Heads fans] that would make friendships immediate.” What's that sensibility?

They're pretty bookish. One of the things I thought interesting was how underwritten the songs are. They're not wordy, really, but the sensibility is so fundamentally literary. Usually people think about Leonard Cohen or Bob Dylan or somebody recent like Craig Finn, who have these cascades of descriptions and evocations. Byrne never did that and it doesn't seem like there was ever a phase in his songwriting career where he was even thinking to do it. But in another way I think Talking Heads are a very literary band in their fundamental stance, their ambivalence and sense of inquiry. I think even when he's switched to nonsense lyrics there's a spirit of inquiry that pervades all of Byrne's best work, and "Fear of Music" is dominated by it.

Shares