Perhaps the biggest general election challenge Mitt Romney faces is finding a way to reassure swing voters that he’s not the “severely conservative” ideologue he ran as in the Republican primaries -- without simultaneously angering the GOP base and giving it a reason to sit on its hands in November.

The reason Romney just may be able to pull this off can be traced to an unlikely source: A job offer he received back in 1975.

As one of the top graduates from Harvard’s joint JD/MBA program, the then-28-year-old Romney spurned an array of lucrative employment possibilities across the country and accepted a position with the upstart Boston Consulting Group, just a few miles from campus. With that decision, Romney and his young family planted their roots in Massachusetts, meaning that when Mitt ultimately turned his ambition to politics, he did so in one of the most Democratic states in America.

Thus when he ran for the U.S. Senate in 1994 did he distance himself from Ronald Reagan, insist that “I don’t line up with the NRA,” play up his previous support for a Democratic presidential candidate, promise to do more for gay rights than Ted Kennedy, and establish his pro-choice bona fides by sharing a wrenching personal account of a back-alley abortion gone bad, vowing that “you will not see me wavering on this.”

This Massachusetts past caused Romney no shortage of grief in his two bids for the Republican presidential nomination. His abortion position in particular may explain why a significant chunk of his party’s base – evangelical Christians – continued to resist him in this year’s primaries even as his nomination became inevitable.

But now, as he begins his delicate post-primary pivot, he’s positioned to reap some serious benefit from his past. Jamelle Bouie explained why on Monday:

The second thing, and I’ve mentioned this before, is a basic incredulity at the idea that Romney actually sits on the right-wing of the Republican Party. Political observers still assume that we’re working with a “Massachusetts moderate,” who will return to the center as soon as its politically safe to do so.

So because he began his career as a culturally liberal pragmatist, the prevailing assumption of the political world is that this represents the “real” Romney – the kind of leader he originally set out to be, and that he’ll once again become once he’s free of the need to pander to the GOP base. The more the press accepts this frame, the more of a boost Romney will receive, since it will encourage swing voters to give him the benefit of the doubt, brush off the far-right positions he took in the primaries, and ignore Democratic efforts to cast him as an extremist.

In this way, Romney may not have to pick a big fight with his base; a subtle break with the right – or even the hint of one – may be enough for the press to remind voters that he’s really a Massachusetts moderate.

Of course, even if you accept this view of Romney, the fact remains that he’d be just as beholden to the right as president as he’s been during the primaries. But beyond that, as Bouie notes, there’s just no clear line between where Romney’s been faking his conservatism and where he really means it. For all we know, the “real” Romney actually does think Paul Ryan’s budget is “marvelous,” and actually does believe all – or most – of what he’s been saying these past few years. This prompted the Daily Kos’ Jed Lewison on Monday to pose this hypothetical on Twitter:

A useful thought exercise for journos convinced Romney is truly a moderate: what if he'd been governor of Idaho?

Actually, this isn’t really a hypothetical, because more than a decade ago Romney actually did – very briefly – begin positioning himself to run for governor of a very conservative state.

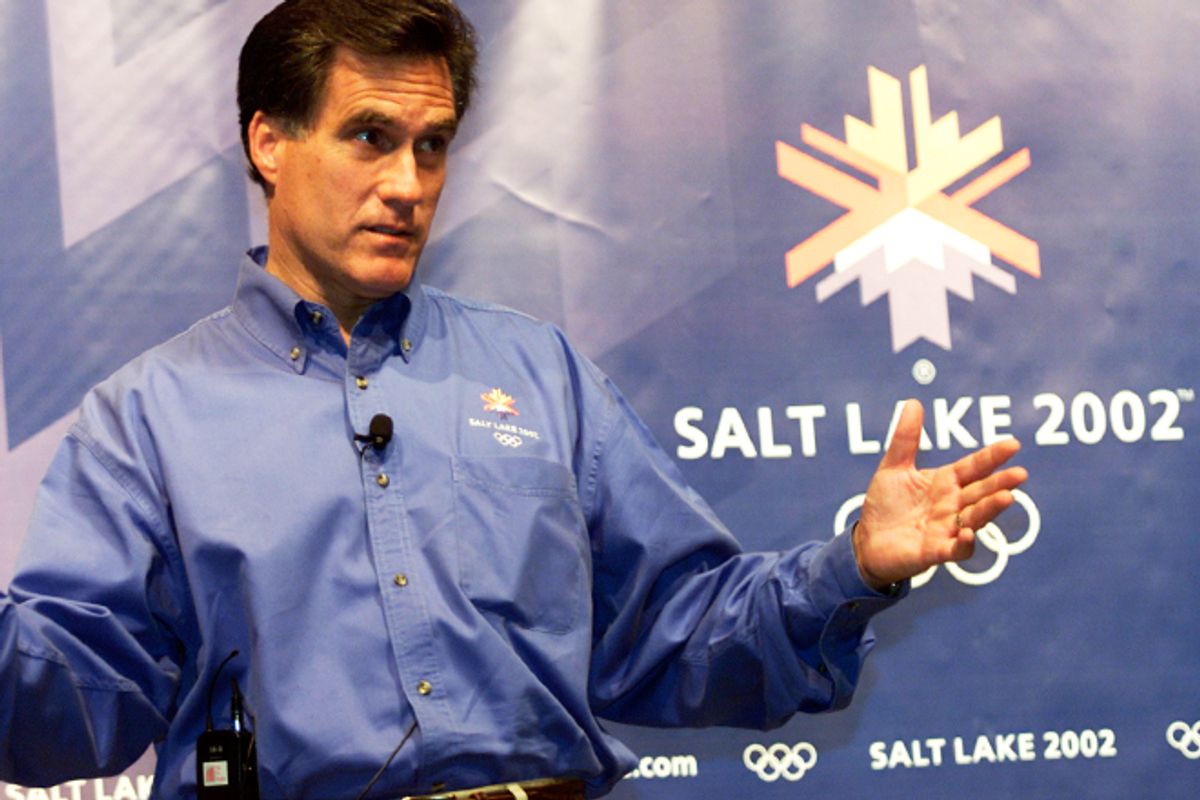

It’s a chapter of his political story that doesn’t receive much attention, but in 2001 Romney was confronted with a very serious dilemma. He was living in Utah, overseeing preparations for the Winter Olympics, and badly wanted to get back into politics. But there was nothing to run for in Massachusetts, where both Senate seats were in safe Democratic hands and a Republican governor – Jane Swift, elevated to that position when Paul Cellucci left to become ambassador to Canada in early ’01 – was set to run for a full term in 2002.

At 54, Romney knew the clock was ticking, and – with some friends urging him on – began considering whether he’d be better off staying in Utah. There was no guarantee the governorship would be open in 2004, but it seemed likely that Republican incumbent Michael Leavitt would decline to seek a fourth term. With his reputation as the savior of the Salt Lake Games and his money, Romney was an attractive prospect. The problem: Utah’s Republican electorate is about as conservative as they come, and statewide candidates are at the mercy of a convention dominated by the GOP’s even more conservative base. Republicans would have no shortage of post-Leavitt options – they ultimately went with a guy named Jon Huntsman – and Romney’s cultural liberalism threatened to kill his candidacy before it began.

Which is how this story landed in the Salt Lake Tribune on July 11, 2001:

While Salt Lake Organizing Committee President Mitt Romney insists he has no thought of using the 2002 Winter Games as a springboard to Utah elective office, he and his supporters are busy attempting to rewrite the history of his public position supporting abortion rights.

It is an issue that could seal the fate of any aspiring Republican politician in conservative Utah.

"I do not wish to be labeled pro-choice," Romney wrote this week in a letter to the editor of The Salt Lake Tribune.

"I have never felt comfortable with the labels associated with the abortion issue. Because the Olympics is not about politics, I plan to keep my views on political issues to myself."

Romney allies in recent days also contacted news media organizations to challenge the "pro-choice" description of Romney used in a recent Tribune story exploring his political prospects in Utah or Massachusetts…

The story also quoted a Romney friend explaining that Romney had only defined himself as a passionate defender of abortion rights in Massachusetts because “he was running against Ted Kennedy in a state that was 80 percent pro-choice and to have any chance at all, he was waffling.”

Nothing more ever came of this, mainly because Swift’s standing in Massachusetts rapidly declined in the second half of ’01. By the time the Olympics wrapped up, panicked Bay State Republicans were begging Romney to run, and a poll put him 63 points ahead of Swift in a potential primary. There was no more need for a Utah option.

The story is telling, though, because it speaks to how Romney would have presented himself if he’d launched his political career in a red state instead of Massachusetts. There would have been no need for him to commit any of his crimes against conservatism; the pressure to conform would have been coming from the right side. This Mitt Romney would have faced a far less awkward transition to the national Republican stage – but received no benefit of the doubt from the media as the GOP’s presidential nominee.

Shares