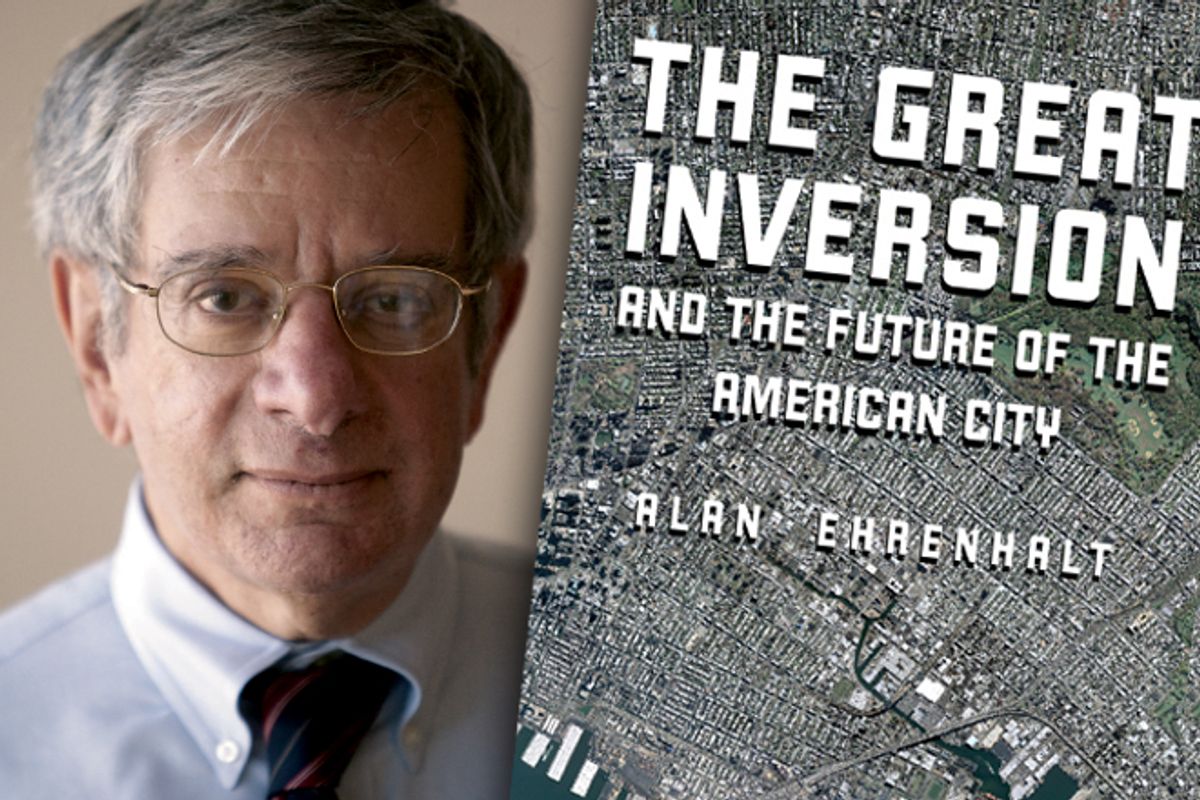

Exactly how this happened, however, doesn't get as much ink. We just assume that a lot of the kids who watched "Friends" in the '90s decided they'd like to engage in witty repartee at Central Perk. But that's just a small slice of what caused the massive shift that Alan Ehrenhalt details in his new book, released this week, "The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City." In a wide-ranging survey of gentrified urban cores, struggling exurbs and outer-ring suburbs that went from lily white to multicultural seemingly overnight, he identifies the trends, policies and mayors that propelled the largest migration since the postwar suburban boom, and speculates on what our cities will look like 10 years down the road.

The revitalization of cities seemed to come out of nowhere, but you write that it was actually the result of deliberate efforts and policies. For instance, Chicago laid the groundwork for a resurgence, while other Midwestern cities missed out. What did Chicago do that, say, Cleveland did not?

In Chicago's case there were two factors: One is that Chicago is simply the biggest, so it inherits the title of Magnet City of the Midwest. That gave it an edge. But it's just as true that Mayor Daley the First had a clear idea that people would want to live downtown, and he made it possible for developers to acquire land there. Similarly to what New York City and Philadelphia did, he offered tax incentives to help the city center come back. Now, you can waste a lot of money on tax incentives if no one wants to live downtown. The market has to be right.

Of course, the flip side is more immigrants and working-class families now living in the suburbs, which has complicated politics in places like Gwinnett County, a suburb of Atlanta, because all these different immigrant groups have a harder time uniting on issues. Are we looking at a future of the ungovernable suburb?

Gwinnett County is interesting because the residents are now a nonwhite majority, yet it's still all white Republicans on the council. It's fairly common for a traditional white power structure to remain when diversity comes in. In Chicago, you had an Irish power structure in neighborhoods long after they became majority black. But yes, one myth is that Asians are Asians when it comes to politics, but each ethnic group is different, politically speaking. And another thing that's clear is that African-Americans and Hispanics go their separate ways -- the immigrants tend not to move into the African-American areas.

The suburbs themselves break down into different factions, too. You've got the outer suburbs, like Gwinnett County, which are seeing a true inversion, and the inner suburbs, which often still suffer from high poverty and high crime. I would think that as the inner cores of cities become more and more expensive, these inner-ring suburbs would inevitably gentrify completely. Is that too simple an assumption?

I think it's a little too simple. The prewar inner suburbs -- the Chevy Chases [in Maryland], the Brooklines [in Massachusetts] -- those will do fine. But the ones built after the war, where the housing stock is smaller, those are going to be difficult to gentrify.

Right, I was fascinated to learn how small the houses were in Levittown on Long Island, the most famous postwar suburb.

Levittown houses were tiny. You don't see many remnants of the original houses there anymore. Today, the average suburban house size has gone from 1,000 square feet to a little over 2,000 square feet.

Transit has benefited greatly from the Great Inversion -- ridership has surged in many cities. Why has gentrification led to increased ridership? It's not as if working-class people don't take the train.

I think the boost comes from leisure travel. You have gentrified neighborhoods to which people are going on weekends and evenings. And while they have a fair number of commuters, most of the cities that have developed light rail are seeing large amounts of non-business-related travel on those lines, too. I think it's also important to make the point that development comes in once the tracks go in. Once you lay down light rail, developers begin to have confidence that this is a neighborhood where you can invest.

This whole idea of a Great Inversion has its naysayers, people who think the shift is temporary and the suburbs will be ascendant again once the economy picks up. Obviously you think that's not the case.

I don't think [the Great Inversion] is 100 percent guaranteed by any means. Nor do I think tens of thousands of people now living in the exurbs are going to head for the inner city. What's more likely to happen is that Generation Y will show a preference for urban living. Now, that might mean "urban living" outside city limits. There's simply a limit to how many people can live in the city, and at times there will be more demand than supply. So urbanizing the suburbs, creating a city out of a piece of suburbia, creating town centers, grids, that could make up the difference.

Could that, in turn, make the exurbs the new suburbs, residing on the edges of these newly urbanized towns? Many exurbs have been struggling because of foreclosures, high gas prices, etc. If today's suburbs urbanize, could that help revitalize them?

I think some of the exurbs may stay vital, but many of the people who will move to them will be immigrants and the lower-middle class. What you're not going to see is a mass movement of wealthy people to the exurbs. That's not going to happen.

Should we feel upset or angry about the Great Inversion? It seems like we're talking about the mass displacement of millions of people. Or are we talking about everyone getting what they want: wealthy people getting to move to urban cores, and immigrants finally getting a shot at a lawn and a two-car garage?

I look at it as an expansion of choice. We went through most of the postwar period where there wasn't a choice to live in the inner city if you had money, and there wasn't a choice to live in the suburbs if you didn't. There were just too many factors working against it. Now people who want to live 40 miles out can live 40 miles out, and there's more opportunity for people to live in the inner city, too.

Shares