The two main Democrats vying to represent their party in Wisconsin’s June 5 recall election share a dubious distinction. Tom Barrett and Kathleen Falk have both previously run in statewide general elections – and they both lost.

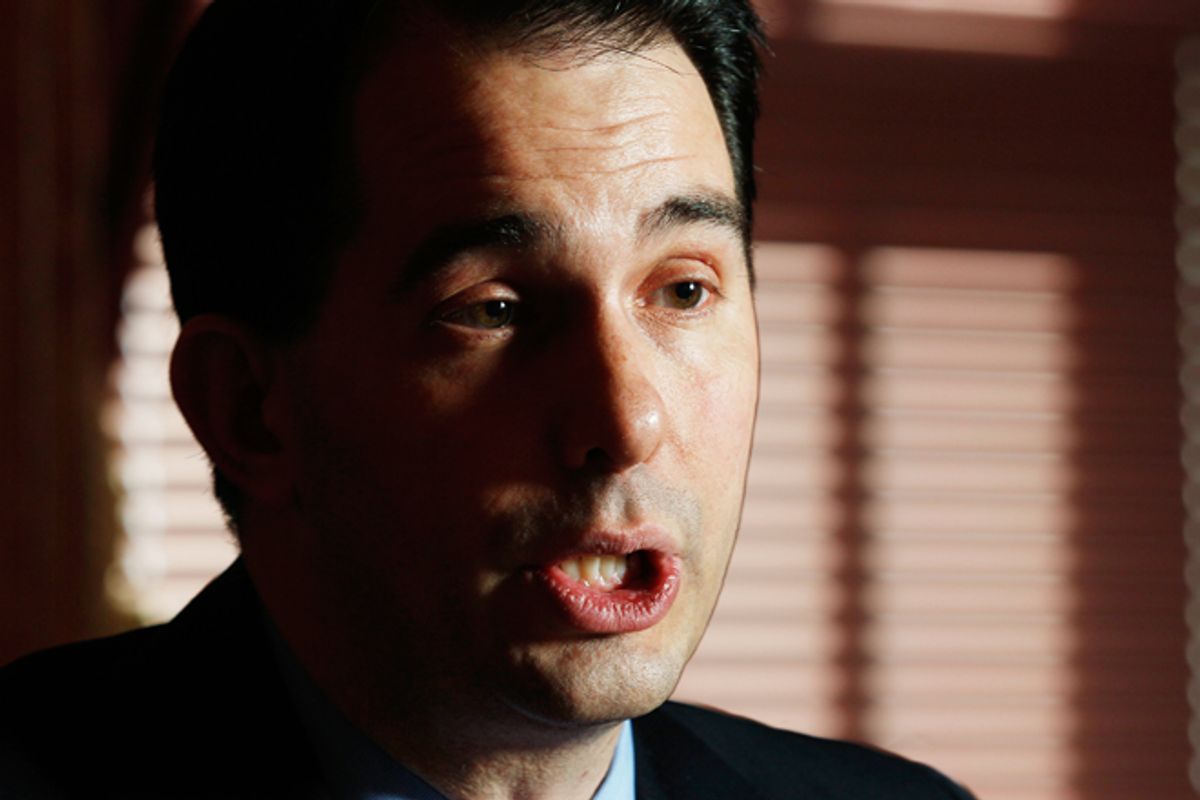

Barrett, the Milwaukee mayor who currently leads the Democratic race, was defeated by 52 to 47 percent in the 2010 gubernatorial race by Scott Walker, the target of the recall effort, while Falk fell about 9,000 votes short – a margin of less than 0.5 percent – when she ran as her party’s candidate for attorney general in 2006.

These defeats create a curious backdrop for the current Democratic race, in which electability looms as an unusually important consideration. By all measures, Wisconsin voters are divided almost exactly down the middle on whether to retain Walker, who boasts passionate, near-universal support from Republicans and bottomless financial resources. For Democrats, there is essentially no margin for error.

“We don’t have any luxury but taking someone with the broadest possible appeal,” former Rep. David Obey told Salon earlier this month.

Obey judged Barrett the strongest candidate and endorsed him a few weeks ago. His assessment seems to be the prevailing one among each party’s establishment. Barrett, who is typically seen as more moderate and low-key than Falk, has also been endorsed by Sen. Herb Kohl, Reps. Gwen Moore and Ron Kind, and former Rep. Steve Kagen. Republicans, for their part, have communicated their desire to face Falk, with the GOP’s state Senate leader even suggesting that members of his party might participate in the Democratic primary on her behalf.

“From the Republican standpoint, they were delighted that she got in the race,” Brandon Scholz, a Wisconsin GOP consultant, told Salon.

That Falk is widely considered an inferior candidate is partly due to the perception that the general election loss she suffered is a more ominous portent than Barrett’s defeat.

Barrett’s loss came in one of the most catastrophic election years Democrats have ever encountered. Nationally, the party lost more than 60 seats in the House and six in the Senate, along with a host of governorships and state legislative chambers across the country. In Wisconsin, the carnage was particularly acute, with Democrats losing a U.S. Senate seat they’d held for 18 years, two U.S. House seats and both houses of the state Legislature. Thus is there a tendency to give Barrett a pass on his loss.

“Five points was considered razor-thin in 2010,” said Joe Wineke, a former state Democratic chairman who is neutral in the Barrett-Falk race.

Falk, by comparison, lost in a year that was the mirror image of ’10. It was in 2006 that Democrats channeled fatigue with George W. Bush, the Iraq War and Republican congressional corruption into a midterm tidal wave. The party won back the U.S. House for the first time in 12 years and picked up the Senate too, while in Wisconsin Democrats easily retained the governorship and a U.S. Senate seat, gained a congressional seat, and swept to control of the state Assembly.

That Falk couldn’t in this climate beat a rather generic Republican opponent in a down-ballot contest for an open seat sure seems like an indictment of her electability. Across the country, Republicans failed in ’06 to unseat a single Democratic incumbent governor, senator or House member. For them, the Wisconsin attorney general’s race was one of the very few highlights of what was a very dark Election Day.

To some, the ’06 outcome is proof that Falk, who served for 14 years as the executive of Dane County, a bastion of liberalism and the home of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is too easily associated with the left edge of her party.

“She has that Dane County moniker that screams, ‘I’m a liberal!’” Scholz said.

“Madison is not thought of fondly outside of Dane County, and it’s what she’d got emblazoned across her forehead.”

Look closer, though, and a more complicated picture of the ’06 election emerges.

The story of Falk’s candidacy begins on the night of Feb. 23, 2004, when a state vehicle being driven by the incumbent Democratic attorney general, Peg Lautenschlager, veered off the road and into a ditch. Lautenschlager claimed she’d fallen asleep at the wheel, but her blood alcohol level was measured at 0.12 percent. She was arrested, charged with drunken driving, and pleaded guilty a few days later, losing her driver’s license for a year. But she refused calls to resign and vowed to seek a second term in '06.

Many Democrats, particularly liberals who admired the activist bent Lautenschlager brought to her work, rallied around her. But others feared her presence on the ticket would give Republicans an easy target, cost the party an office it had controlled since 1990, and maybe even imperil other Democrats on the ballot. One of those Democrats was then-Gov. Jim Doyle, who already had a contentious relationship with Lautenschlager and who urged Falk to challenge her. At the time, Falk was something of a rising star in the party. Elected Dane County executive in 1997, she’d won notice with a surprisingly strong showing in the 2002 gubernatorial primary, which Doyle won (and in which Barrett edged her out for second place). Since Democrats controlled the governorship, both Senate seats and her local congressional seat, taking on Lautenschlager represented her only immediate chance to move up. So she went for it.

It was a heated, expensive and close campaign. As the September vote approached, polls showed victory within the resilient Lautenschlager’s grasp, prompting Falk to authorize an attack ad that played up her opponent's DUI conviction. That may have made the difference, with Falk pulling out a 53-47 percent win on primary day. The most notable feature of the results had to do with geography: Dane County’s liberal electorate revolted against its favorite daughter Falk and sided with Lautenschlager by 20 points. But Falk won 51 of the state’s other 71 counties, many of them by crushing margins.

“In the primary, she would have been the more conservative of the two,” noted Wineke. “The liberal base in Wisconsin was for Lautenschlager.”

Waiting for Falk in the general election was J.B. Van Hollen, an ambitious 40-year-old former U.S. attorney for western Wisconsin. Republicans quickly sized him up as their best – and only – chance for a statewide victory, with Doyle and Kohl safely ahead in their contests. At the same time, Falk was left scrambling to rebuild her war chest and had only seven weeks between the primary and general election to do it. Party unity was an issue, too. “Peg [Lautenschlager] was hurt, and hurt by the fact that a friend would challenge her,” Winike, the state party chairman at the time, recalled.

Toward the end of the campaign, the state’s leading business-interest group, Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, poured millions of dollars into an independent ad campaign that targeted Falk.

“Her polling showed her up 10 points just before the election,” her current campaign spokesman, Scott Ross, said, “and then they just got blistered.”

Republicans cunningly sought to exploit lingering liberal bitterness over Lautenschlager’s defeat. “You can still be a good Democrat and vote against Falk,” read a flier that was distributed just before the election. The official margin of victory for Van Hollen was 9,071 votes, a difference of 0.4 percent. In Dane County, Falk received 11,850 votes fewer than Doyle; had she simply run even with him on her home turf, she would have won the race.

“Those were folks pissed off that she challenged Lautenschlager,” said Wineke. “So you could make an argument that the leftist base that refused to vote for Kathleen cost her the election.”

In a campaign against Walker, Falk’s backers are quick to point out, neither party unity nor money would be much of an issue. Even if Democrats can’t match the governor and his allies dollar for dollar, they’ll have more than enough to be competitive, something that wasn’t necessarily true for Falk when she ran into the Manufacturers and Commerce buzz saw.

Falk’s image as the more liberal candidate reflects not just her Dane County roots, but also her tight alliance with some of the state’s largest labor groups, which are spending heavily on her behalf. Ross dismisses the “too liberal to win” charge by noting that many previous statewide winners – like Doyle and Russ Feingold – hail from Dane County and that “since the dawn of the Democrats versus the Republicans, whoever is the Democrat running in a high-profile race is always [portrayed as] the tool of the unions.”

Those who doubt Barrett’s electability make two arguments. One is that, for lack of a better term, he’s too average – that he doesn’t instantly offend many voters, but that there’s also not much about him that inspires them. So while it’s true that he was running under what amounted to impossible conditions against Walker in ’10, it’s also not as if he performed surprisingly well and came closer to pulling off a win than a generic Democrat would have. The Barrett side’s counter is that his low-key style is a much better match for the current climate, with state politics so intensely polarized.

“In Tom Barrett’s case, the strength is also a weakness to some,” Wineke said. “Tom Barrett is viewed as a quintessential good guy. Very few people that I know do not like Tom Barrett. He’s just a good guy.”

The other knock is that Barrett’s nomination could make it easy for Walker to deflect Democratic attacks on the issue that triggered the recall push in the first place. As Milwaukee’s mayor last summer, Barrett used the restrictions on collective bargaining that Walker had imposed to force concessions from the city’s public employees. He says he had no choice – that the state slashed Milwaukee’s aid, that he couldn’t make up for it with property taxes, and that the only alternative was mass layoffs and deep cuts in city services.

“Blaming Tom Barrett for the actions in the Milwaukee budget that were forced by Gov. Walker is like blaming a surgeon who does surgery after a patient is hit by a truck,” Obey said recently.

Still, Falk and her allies have happily pointed out that she was able to win concessions from public employees at the bargaining table – not by a unilateral decree made possible by Walker’s law.

Polls give Barrett a clear, but not overwhelming, lead over Falk. But each side concedes that no one really knows what the voter pool will look like in the May 8 primary. Between now and then, both candidates are left to convince their fellow Democrats that what sank them in their last statewide campaigns won’t do the same again this time.

Shares