![]() Whatever interactive fiction is (and we’re still figuring that out) it suffers from all the problems of traditional fiction and then some. The vast majority of novels and short stories aren’t much good, but when a branching fiction — along the lines of the old “Choose Your Own Adventure” children’s books — fails to engage, the first impulse is to blame the form rather than the content. Let “Frankenstein,” just released by Inkle Studios and Profile Books, serve as a reproach to that reflex. The app is a creative, subtle and sensitive adaptation of Mary Shelley’s classic novella, and it has singlehandedly renewed this critic’s hopes for interactive fiction.

Whatever interactive fiction is (and we’re still figuring that out) it suffers from all the problems of traditional fiction and then some. The vast majority of novels and short stories aren’t much good, but when a branching fiction — along the lines of the old “Choose Your Own Adventure” children’s books — fails to engage, the first impulse is to blame the form rather than the content. Let “Frankenstein,” just released by Inkle Studios and Profile Books, serve as a reproach to that reflex. The app is a creative, subtle and sensitive adaptation of Mary Shelley’s classic novella, and it has singlehandedly renewed this critic’s hopes for interactive fiction.

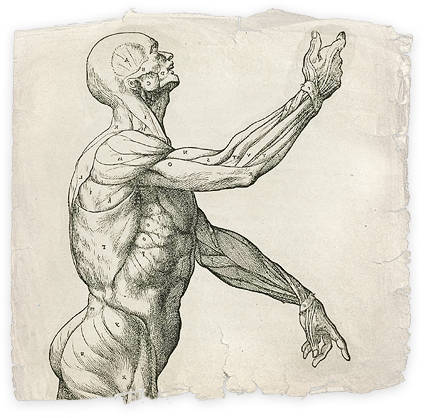

What this “Frankenstein” isn’t is a replication of the source text with the addition of a lot of digital doohickeys like sound effects and illustrations that animate when tapped. The app is all about the text, even if it is beautifully framed by period art and anatomical illustrations. The reader is presented with a screenful of narration and then offered one or more responses to it. The preferred response, when tapped, delivers up another screen of text. (In an absurdly pleasing visual touch, these appear as sheets of paper fasted together by straight pins.) According to the press materials, the reader’s responses will shape the way the narrative is presented, although not to the degree of substantively changing the plot.

This is an important point. The pleasure of storytelling lies in the dynamic between the surprising and the inevitable. The reader wants to feel the story is going somewhere, that its events follow from each other in meaningful, but not too obvious ways. When a story can go anywhere, it feels meaningless. In Mary Shelley’s novella, which is saturated with the Western tradition of the tragedy, Viktor Frankenstein’s character is such that he must create a monster, and the monster’s body is such that he can never belong among human beings however much he yearns to. A “Frankenstein” that ended with either misfit finding a comfortable place in the world would be a travesty.

But that doesn’t mean the reader doesn’t long for the story to unfold otherwise; that’s the nature of tragedy. The great insight that writer Dave Morris brings to this adaptation of the novel is that while a reader cannot significantly change the outcome of the story, the interactive element can change the shading and flavor of the tale. It can be mournful and reflective or action-packed. The creature and his creator can show greater or lesser ambivalence about their own behaviors. The ambiguity of both figures is baked into Mary Shelley’s novella, and while Morris has nearly doubled the word count of the original, this mostly amounts to playing up or down what’s already there.

Morris — a novelist who has written graphic novels, games and, yes, Choose-Your-Own-Adventure stories for kids — has changed the original text in other ways, as well. (Let’s take a moment here to point out to all future narrative app developers that hiring a real writer who actually knows what he or she is doing is totally worth it.) He’s moved the setting to revolutionary France, a choice that shows shrewd understanding of the idealistic political climate that affected Shelley’s thinking; the new Republic is its own kind of Frankenstein’s monster. He’s also eliminated much of the 19th-century framing of the tale and converted it into two present-tense narrations. One is Frankenstein’s dialogue with either himself or a (possibly imaginary) companion. The other is a second-person account of the monster’s first weeks of life as it spies on a family of dispossessed French nobility and has the chance to observe the loving relationships it can never enjoy itself.

Morris presents the reader with choices I’ve not encountered in other interactive fictions. Is humanity mostly good, or mostly evil? Does the most recent development make you (the monster) feel hope or despair? Is the revolution the dawn of a brave new world or a descent into chaos and barbarity? While I’m usually skeptical that present-tense narration increases the “immediacy” of a story, in this case, it really does work, particularly in the sections concerning the monster. Depending on your own outlook, you may urge him to keep trying to connect with humanity, or promptly forward him on to homicidal rage.

In either case, the narrative is shaped not by the reader deciding to turn left or right, to go down into the cellar or to get out of the house — the usual actions offered on the choose-your-own menu. Instead, the options have more to do with personality and interpretation, beliefs and ideas. As a result of the reader’s choices, the characters seem more like him- or herself, with a concurrent ratcheting up of emotional investment. To my surprise, I found myself more moved by this adaptation of the Shelley novel than I have been by the source text. (Although the app does include the original if you want to compare and contrast.) This is the only interactive fiction I’ve ever read with that quintessential, old-fashioned readerly avidity: the hunger to know what happens next. Of course, I already knew, but that didn’t matter at all.