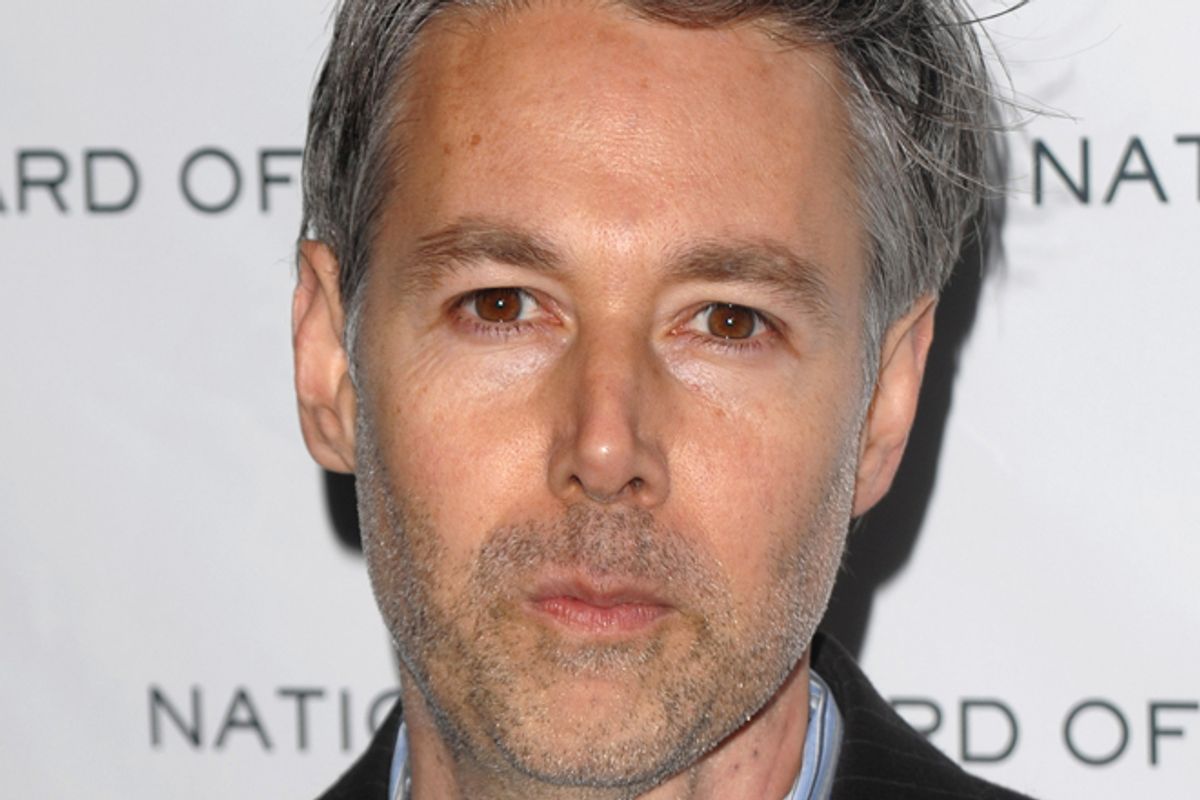

For a band that broke out with the indelible slacker declaration “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party),” the Beastie Boys weren't exactly the most likely group to turn into human rights activists. Yet it was the trio -- that included Adam Yauch, the Buddhist who lost his battle with cancer Friday at 47 -- that led the battle for Tibet in the late '90s at a time when changing the world through music events wasn’t so fashionable. Their transformation from bratty, delinquent teenagers into altruistic, socially engaged cultural figures may have paralleled the coming-of-age and awareness of a generation of Americans.

Starting as a teenage punk band in the late '70s, the Beastie Boys latched onto the hip-hop culture that was rising all around them, hooked up with young producer Rick Rubin and became a mainstay of his new Def Jam label. Armed with their 12-inch hits that preceded it, the debut “Licensed to Ill" was a time bomb on hip-hop that few albums were, creating instant anthems, top-rated videos and opening slots on tours from Public Image Ltd. to Madonna to Run DMC.

They did so with personas that imitated the nicknames of rap: Yauch was MCA, the first party-crasher to burst through the door in the “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party!)” video, alongside Mike Diamond’s Mike D and Adam Horowitz’s Ad Rock. It wasn’t just that they were gangly white guys in a field of African-American expression, it’s the goofy body language they explored that showed them to be heirs to goony physical borough comedy dating back to the Bowery Boys and the vaudeville that preceded it.

The real wit came in their perfectly honed rhymes combining brand names and unexpected pop culture references embedded in the usual braggadocio trade-offs. “I’m not ‘James at 15’ or ‘Chachi in Charge’/I’m Adam and I’m adamant about living large,” went one couplet. “Got more stories than J.D. got Salinger/I hold the title and you are the challenger” was another.

By their second album, 1988’s “Paul’s Boutique," they were unveiling themselves as genuine artists, with an exhilaratingly dense, sample-heavy masterpiece, produced by the Dust Brothers, that would stand as their greatest, even as their rhymes (“Hey Ladies!”) disguised them in clown masks. By then the Beasties were patrons in a multimedia arts empire that included their own Grand Royal label and magazine, setting style even when they weren’t in the recording studio.

Their ever-creative videos gave a showcase for someone who would become a leading and sought-after film director, Spike Jonze. Jonze's deliriously old-school cop show approach to “Sabotage” may have led to a whole string of similarly mustachioed big-screen homages. When Jonze failed to win the MTV Video Music Award for best direction in 1994, it was Yauch, disguised as his character Nathanial Hornblower, who stormed the stage to protest -- years before Kanye West would have a similar idea.

It was under the name Hornblower that Yauch directed a number of the Beasties’ music videos. By organizing the fan-shot footage that combined to make the concert film “Awesome, I Fuckin’ Shot That,” he was a pioneer in creating the new field of fan-interactive filmmaking. He continued that interest when his label Oscilloscope Laboratories, which had produced a comeback album for Bad Brains, became more of a film concern, producing Yauch’s basketball documentary about high school hopefuls in 2006, “Gunnin’ for that No. 1 Spot” and later the acclaimed indie films “Wendy and Lucy,” “The Messenger” and the art-house favorite about street artist Banksy, “Exit Through the Gift Shop.”

It was his Tibetan activism that may have been closest to his heart, organizing a few huge series of Tibetan Freedom Concerts that began in San Francisco in 1996 and continued in subsequent years in New York and Washington, D.C.. They had the biggest gathering in 1988, drawing 120,000 and a lightning strike that injured 12. Subsequent concerts in Tokyo and Taipei in 2001 and 2003 drew fewer fans, but by then they had raised millions of dollars and succeeded in drawing enormous attention to the issue.

This seriousness didn’t spoil the deep goofy humor of their approach, although the diagnosis of Yauch’s cancer cut into plans for videos or tours to accompany their latest albums. He was not physically present either at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in Cleveland last month -- a ceremony that will ironically get its first national telecast this Saturday on HBO.

Their portion of the event, which concluded with the induction of the Red Hot Chili Peppers (who dedicated their live performance to Yauch), was the only time during the ceremony when the Cleveland crowd sang along to the film clips being shown. “There’s no adequate measure for the impact that the Beastie Boys had on rap music and yours truly, Public Enemy, during our formative years, ” Chuck D says in the induction ceremony. "They challenged the conventions in the music business and made up their own rules about what it means to be world class hip-hop cats." More than that, he added, they always insisted on "maturing as musicians and human beings."

Unlike other inductees at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Mike D and Ad Rock did not take the stage to perform, leaving a medley of their hits to the Roots, with help from Kid Rock and Travie McCoy of Gym Class Heroes. Despite his absence, Yauch wrote an acceptance speech Ad Rock read that may serve as his last public message to his fans: "I'd like to dedicate this award to my brothers Adam and Mike, who walked the globe with me. To anyone who has been touched by our band, whose music has meant something to, this induction is as much ours as it is yours."

In the same way, the group's maturation from partying hooligans to responsible world citizens mirrored their fans' growth into world awareness. Although their last albums came when they were in their 40s, the Beastie Boys retained the spirit of earlier recordings while slowly injecting more thought, including Yauch's remarkable apology to all women on behalf of rap, in the 1994 track "Sure Shot": "I want to say a little something that's long overdue: The disrespect to women has got to be through. To all the mothers and sisters and the wives and friends: I want to offer my love and respect to the end."

It was Yauch's damnable disease that caused the delay in the release of albums, the impossibility of tours and the inability to make videos that eventually cut into the Beasties' sales. The longer-lasting traces of social consciousness embedded in their message and how they operated -- cutting the parenthetical clauses from their first hit's title makes it "Fight for Your Right" -- will make the spirit of the Beasties endure in the activism of the generations that followed.

Shares