In the 15 years since my mother has been gone, she has become a mythical figure in my life. She was a woman to be revered, but also one so complicated and so different from me that I fear I’ll never stop struggling to make sense of her and to accept myself within the context of her shadow.

My mother was 37 years old, twice divorced and childless when she met my father. She had been living in Manhattan for 17 years, having grown up in Connecticut and gone to the Rhode Island School of Design to study painting. She had dozens of friends, went to parties and attended art openings. She smoked pot in the Village and spent Tuesday nights in smoky jazz clubs, sipping martinis and recrossing her legs.

My parents had been set up on a blind date by mutual friends, but the night they were supposed to go out, my mother stood my father up. She’d gone to Long Island that day with a friend to pick strawberries, and by the time she came home, the last thing she felt like doing was going on a blind date with some older businessman from Atlanta.

My mother was funny and quick-witted, and she was almost always up for an adventure. She was also uncommonly pretty, with green eyes, blond hair, a symmetrical face and an easy smile. When she went to sleep that night in June of 1975 in her little one-bedroom apartment on 28th Street, she had no idea that her life was about to change.

My father, at 55 years old, was just entering his prime. In spite of (or perhaps because of) two divorces and three grown children, he was happier than he’d ever been.

He flew first-class wherever he went. He stayed at the Watergate Hotel when he was in D.C. and the Plaza when he was in New York. He winked at stewardesses and drank tumblers of scotch on the rocks. He wore hats and suits and left big tips at fancy restaurants.

He wasn’t used to being stood up, so the next morning he rang my mother’s buzzer at 9 a.m. “Who dares call on anyone before noon on a Sunday in New York?” my mother later wrote about that first encounter in a letter to my father, detailing their courtship. “It had to be you, as they say, and I opened the door with wet hair asking if you wanted a Bloody Mary, which you did, thank God.”

I always try to imagine this moment between them. My mother in the doorway with her wet hair, my father on the threshold in his blue leisure suit, the moment of them not knowing each other and then knowing each other eclipsed in one short breath.

They went to dinner and later flew to my father’s place in Atlanta, making daiquiris with the strawberries my mother had picked on Long Island the day before. They swam in the pool and smoked Camels and talked into the night, their legs dangling into the water, lit from below by the pool light.

They were married three months later on Cape Cod. My father whisked my mother away from New York and set her up in a big house in a nice neighborhood in Atlanta. He paid off all her debts, bought her a cream-colored convertible and opened a credit card in her name in every department store. I was born two years after that.

For the next decade -- before my father unexpectedly went bankrupt following the stock market crash of 1987, and before my parents were both diagnosed with cancer within months of each other -- we lived a blissful and privileged existence. My mother had quickly charmed her way into Atlanta’s upper social echelon, and it wasn’t uncommon for our dining room table to be inhabited by local political figures and foreign dignitaries.

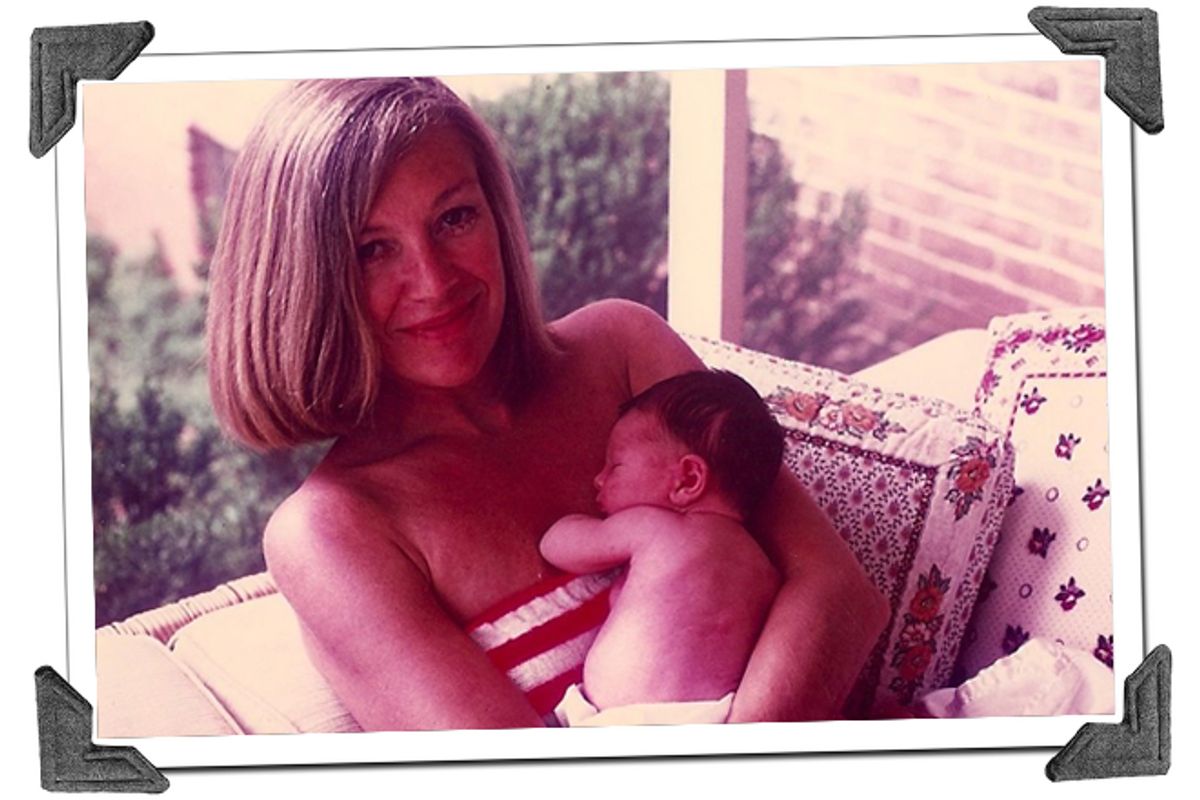

I remained her only child, but motherhood only seemed to enhance my mother’s glamour and sophistication. It added a dimension to her personality and worldview that had, perhaps, been the only thing missing all along. But I wonder what the other carpool moms thought of my mother when she zoomed into the after-school pickup line in her Alfa Romeo, with her blond hair pulled back in a Chanel scarf.

I was 18 when she died of cancer, and I had become the very opposite of my graceful, glowing mother. My teenage years had been rocked by a roller coaster of parental illness, hospitals and private despair. In response, I had become an angst-ridden poet. I wore combat boots, dyed my hair crimson and sported a nose ring. My mother had always embraced these tiny, public displays of rebellion, but the moment she was gone I felt foolish.

I’ll never forget walking down the aisle of a church on the day of her funeral with a shaved head and my first, barely dry tattoo concealed under my shoulder, feeling as though I had utterly failed my beautiful mother in every way possible.

Since she died, I have struggled to forge my own identity in her absence. At times, I have wanted nothing more than to emulate everything about who she was -- something I know I could never really achieve. While I may be outgoing and capable of hosting a memorable dinner party, I have inherited my father’s looks and practicalities, not to mention having retained a deep-seated and dark sense of self-reflection following so much loss.

For many years, I was unsure if I wanted children at all. When I finally decided that I did (within days of meeting my husband), I knew that I wanted to be a younger mother than mine was. My daughter was born a few weeks after my 31st birthday -- almost a decade before my mother herself bore me -- and now, as I approach my 34th birthday, I am due with my second.

Every inch of motherhood, for me, has been stitched with the essence of her. Throughout my 20s, I made valiant and sometimes senseless attempts to bring my mother into my life again. I lived in the places where she once lived. I learned how to cook and throw dinner parties. And more often, I simply took myself to the very brink of life in hopes that if I tottered just enough, she might appear to pull me back from the edge.

But it was truly in motherhood that I found her again, even though our experiences couldn’t be more different. My husband and I live in a tiny rental house in Los Angeles and both work as writers, struggling to pay our child’s preschool dues. I can often be found at the playground, even if I am one of the few mothers actually wearing mascara and earrings. As I write this, my body is swollen with another child, something she never ventured to do.

Despite those differences, motherhood has brought her back into my life, and it has given me an opportunity to embrace my own path as a woman and mother. I hear her in my voice when I comfort my daughter by crawling into bed with her at 3 a.m. when she has woken from a nightmare, when I stop to marvel at a snail traveling through the grass, and especially during dinner parties when I catch myself offering my 3-year-old bits of brie or Marcona almonds.

In adulthood, it has occurred to me that all of us are living reactions to our parents. Whether they loved us or not, whether they were present or absent, whether they kept us safe or recklessly abandoned us to harm’s way, we move forward into life walking paths they etched out decades earlier. It also often occurs to me how grateful I am to the woman who loved me fiercely enough to remain true to who she was, even in the complicated throes of motherhood.

Shares