Many people continue to feel influenced and even controlled by the things that happened to them a long time ago. Sometimes, people harbor dark, traumatic memories from childhood. Or fragments of memories — incomplete scenes, uncomfortable feelings, perhaps even a sense of certainty that something specific and terrible happened to them, but little more than this.

Others experienced something traumatic in adulthood that continues to affect them day to day many years later. Maybe an assault has left a person afraid to leave their home or enter a particular neighborhood.

For a certain kind of person this will be the end of the story. What ever experience they endured essentially continues to this day, ever present in the background, shaping the choices made on a daily basis, affecting the quality and range of their life. This kind of person might be angry all the time or feel guilty or afraid. They just accept these states as a part of themselves.

Then there are people who are keenly aware of their experiences, who are psychologically ambitious; they wish to “get over” these historical traumas and might see a therapist to help them.

The therapeutic process takes time, commitment, and funding. Then, insight leads to understanding, which leads to choice. At last, they are free to move on.

It’s such a clean, well-defined structure for the process of healing. Almost like a paint-by-numbers portrait where all those black outlines are confusing at first, but in time, as you apply the correct colors in the right areas, the tangle of lines resolves into a perfectly clear image.

Unfortunately, our brains tend to color outside the line. First, there is the matter of understanding our past and the events that transpired.

Understanding what happened in the past is rarely truly possible. Because true understanding must incorporate context. Not merely what we experienced, but why. And the why requires knowing the motivations of the other people involved. Without the perspective of this context, our understanding will always be biased; it will be from a single perspective: Ours. And therefore, not necessarily accurate or true.

If you are on a highway and you drive past a car accident so severe that the hood of the car has been crushed up against the windshield, you may very well assume the occupants are dead. And perhaps this will haunt you because as you passed by the car, you glimpsed a little girl’s doll on the shelf behind the backseat. One look at that accident was all anybody would need to know what “unsurvivable” looked like. And you have never been able to forget that doll or the little girl who must have loved it and who died in such a terrible crumple of steel and glass. Let’s imagine that you are haunted by dreams where you come upon the accident and you see the doll and you do nothing.

Let’s say that what was unknown to you was that the car was a high-end Mercedes that featured crumple zones designed to absorb the impact of a crash while protecting the occupants within a safety cage. And let’s say that the two occupants inside the car were sitting there as you drove by and the man in the driver’s seat was on his cell phone.

“No, I mean totally like, trashed, totaled. We’re waiting; they’re supposed to send a tow truck. She’s good except she has to pee so she’s—”

“Oh my God, did you just tell Jason that I have to pee? Now he’s going to imagine me peeing. Don’t forget to tell him we found the doll at a tag sale but we need to buy wrapping paper. At least we think it’s the doll.”

“You hear that? Yeah, don’t think about her peeing. And we’re pretty sure it’s the right doll; we had to spend like three hours on Craigslist to find one.”

Imagine that after the tow truck arrives and our couple has been safely installed into a rental vehicle, they don’t really ever think about that crash again except both are pleased with the new car’s color. Neither liked the wrecked Mercedes’ particular shade of red.

In this example, you can see how your entire perception of what happened — and you were a witness — is completely distorted by your point of view.

So, if you were to enter therapy over being disturbed by this wreck, you could spend years discussing why the sight of the doll was so upsetting, and how impotent you felt being unable to stop and help but even if you could stop, what could you have done?

Possibly, the therapist would have you write letters to the dead little girl.

What this really accomplishes is the creation of a sort of personal myth. A series of well-remembered events with finely honed details. As accurate as they may be, they are accurate from only one perspective.

For many years, I believed that one’s past had to be fully understood in order to move through and beyond it. I see now that I was wrong about this. I know now that scrutinizing one’s past and trying to gain understanding and “make peace” with it is a kind of addiction that keeps one focused on the past and not on the present.

As with any addiction, the first step to overcoming it is to see it.

And once you see it, you have to stop it.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Once the current moment moves into the past, it is entirely gone. It ceases to exist except in documents, photographs, and an impression left in a sofa cushion. The past — and all the moments it contained — are no longer sharing this world with us.

They are no more real than Cinderella.

To spend time — year after year — in therapy or on your own thinking about your past and forming conclusions and stitching the elements into a narrative that you can name, “the truth,” in order to be “free” of it, is not how you become free from your past.

The past does not need to be reconsidered in the present and given a structure. The events of the past cannot be understood when you are the only element of the past actively engaged in reliving it.

When somebody says, “Therapy has been really helpful to me in terms of resolving some of my issues from the past,” what does this actually, in practical terms, mean?

Or somebody is “haunted” or controlled by their past. How is this possible?

When I first moved to New York, I became friends with a guy who seemed to be exactly the guy I wanted to be. He was very outgoing and had lots of friends and they probably all felt as I did: Like his best and closest friend.

After we’d been friends for almost a year, one night we were out drinking and he told me he had a confession to make, something he wanted me to know about himself.

I nodded and tried to look very sincere and open, while inside my mind it was the Kentucky Derby, with most of the money being placed on female-to-male transsexual. That wasn’t it.

He proceeded to tell me in great detail about the utterly atrocious physical abuse he’d experienced at the hands of his father and mother during his childhood. It was well beyond anything I myself had ever come close to experiencing.

After this evening, my friend spoke of his past abuse frequently. And I realized that all the time we’d been friends, all those moments prior to his revelation had probably been, in his mind, moments leading up to The Telling.

Only after The Telling could he be fully himself with me. His story of his past abuse was a large part of his identity. It was a protected secret that was kept out of view for acquaintances and coworkers. Only after a measure of trust and intimacy had been formed would there be almost a ceremony in which he detailed his abuse. Rather like unwrapping, slowly, an extravagant gift one knows is going to blow the mind of the recipient.

When we first became friends it had amazed me that he was single. I now understood that he was single because of

how guys reacted when my friend finally revealed his history. It was like encountering a new person. And my friend’s abuse was now like a third person with us wherever we went.

Who could blame him? It was a wonder he was still alive.

Today, I see it differently.

My friend is a dramatic example of somebody who is haunted by their past. But because the past is gone, how does it haunt? Of course, it does not. The past does not haunt us. We haunt the past. We allow our minds to focus in that direction. We open memories and examine them. We re-experience emotions we felt during the painful events we experienced because we are recalling them in as much detail as we can.

We enter therapy and discuss our past. We formulate opinions about what happened. We create a rich, detailed world. In therapy or on our own, we focus our attention on something that no longer exists in order to understand or have perspective or acknowledge or own what has happened. And only after we decide this understanding or recognition has taken place do we stop worrying that particular tooth with our tongue.

For years, I believed this was how to live.

I was wrong. It’s how to stagnate.

I know now how to get over the past. It has worked for me in a deeper, more enduring way than any therapy I have ever had.

Writing six autobiographical books is what freed me from my past.

If the books had been cookbooks I expect I would feel just exactly as free. That I wrote six books about my past is the red herring; nothing I have written has in any way altered the past or healed me clean, so no scar remains.

Perhaps the process of writing — being fully in the moment, while I write letter by letter — has soothed me because it’s kept me busy. When you’re busy, you lack the time to fondle your emotional baggage. And if that sounds too reductive, remember we crawled from the swamp. Simple isn’t such a terrible thing to be in this respect.

For the same reason, being out of a job and just hanging around is depressing in a thousand different ways. All you have is time. Sooner or later, you end up wandering around bad neighborhoods inside your head. Neighborhoods like, “They never should have fired me, those assholes.” Which may be true or it may be untrue but it’s irrelevant to everything. It is through work that challenged me and required continuous freshness that I began to occupy not the past but this, right now. My advertising career had not been challenging. Being busy is not the same as being focused. Being focused means being here.

And this, here, this line, that comma.

That’s what freed me from the past. The present kidnapped me. I climbed into its car when it held up its hand and showed me the candy. I hopped right in.

When something from my past upsets me here in my present, it’s because I let my mind think back to the past and grab hold of something.

This is how the past haunts us. We think about it.

Therapy could be of tremendous benefit to “getting over” one’s past if the therapy is focused on specific ways to stop submitting to the temptation to obsess.

Many people with difficult histories carry these histories with them, burnishing the past with each retelling. Sometimes, a particular trauma may be the largest thing we have ever experienced. So we kind of move into it, make it our home. Because there’s nothing in our lives on the scale of that loss or that trauma.

So, you need a larger life. Something that can successfully compete with your past.

To live with your mind in the past — in the name of healing or understanding or overcoming — is to live in a fantasy world where nothing new or original is created. To “understand” one’s past is to handle clay that no longer exists and shape it into a bowl nobody can ever see or touch.

Denial of the painful events in one’s past is the same as obsessing over one’s past. To actively refuse to discuss or think about, if need be, what happened is to imbue it with power. Recycling the past into a new business, a not-for-profit to help others, a workshop, a painting, a book, a song — these are ways to explore the past in the context of the present. These are things people who are actively alive do.

You must never allow something that happened to you to become a morbidly treasured heirloom that you carry around, show people occasionally, put back in its black velvet pouch, and then tuck back into your jacket where you can keep it close to your heart.

Then, when asked to join the pole vaulting club, pull the coach aside and whisper, “I can’t. See” — and remove your gem from your pocket — “this is my terrible thing and as I expected, showing it to you has taken your breath away and made you sympathetic. So I will be excused, I assume?”

Other people will allow you — they will never blame you or challenge you — to use your past as an excuse to not face the normal fears everybody has when facing their future. Even if you were brutally physically assaulted, you must not withdraw because you are afraid it will happen again. This is not a valid exit.

Your fears that it might happen again are perfectly reasonable and justified: It might happen again.

Many people believe that if something really bad happens to them, they have paid their dues and nothing else really bad can happen again. But on the day you attend your mother’s funeral or declare personal bankruptcy, there is no law in the universe that prevents you from also getting a speeding ticket and your first grey hair.

When multiple bad things happen, it can feel like “life is out to get you.” It’s not. And it’s not a sign, either. What you do is, you keep going. You stop waiting for fairness.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

You do not need to work through your past so you can heal. You need to move forward and then you’re as healed as you’re likely to be.

Unless.

Unless you experienced something so unspeakably terrible, something so out of scale in magnitude that it simply doesn’t fit into the past. It is too large to be contained by time or space. And if this is you, the thing you can do for the duration of your existence is to tell your story over and over. So that other people can hear you tell it and they can be moved, changed by it. This can help others.

Which is the single comfort for people who will always remain locked in their history, inside something that is really a different species of awful.

I met somebody whose grandfather had survived the death camps in Germany.

He told me that his grandfather was a very quiet, broken man. He rarely spoke and when he did, he told the same stories about how he survived.

I told him, “Do you listen, every time he tells you?”

He said, “No, I just kind of let him talk and do my thing; I’ve heard it all a thousand times.”

I wondered if he had ever truly heard it once. I suggested he listen, hang on every word and try to see visuals in his mind of the story his grandfather was telling him.

Some stories must be carved into the present and the future by telling and telling again and then again until the story is part of us.

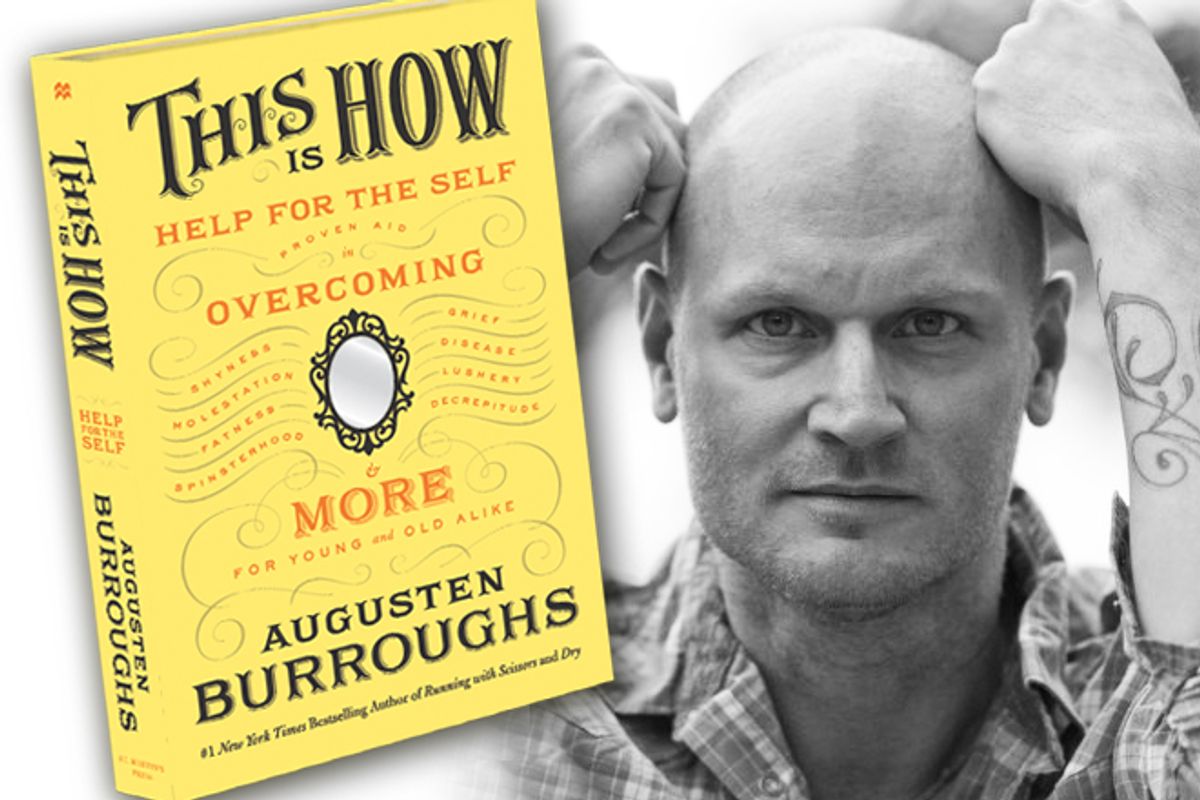

From "This Is How" by Augusten Burroughs. Copyright © 2012 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

Shares