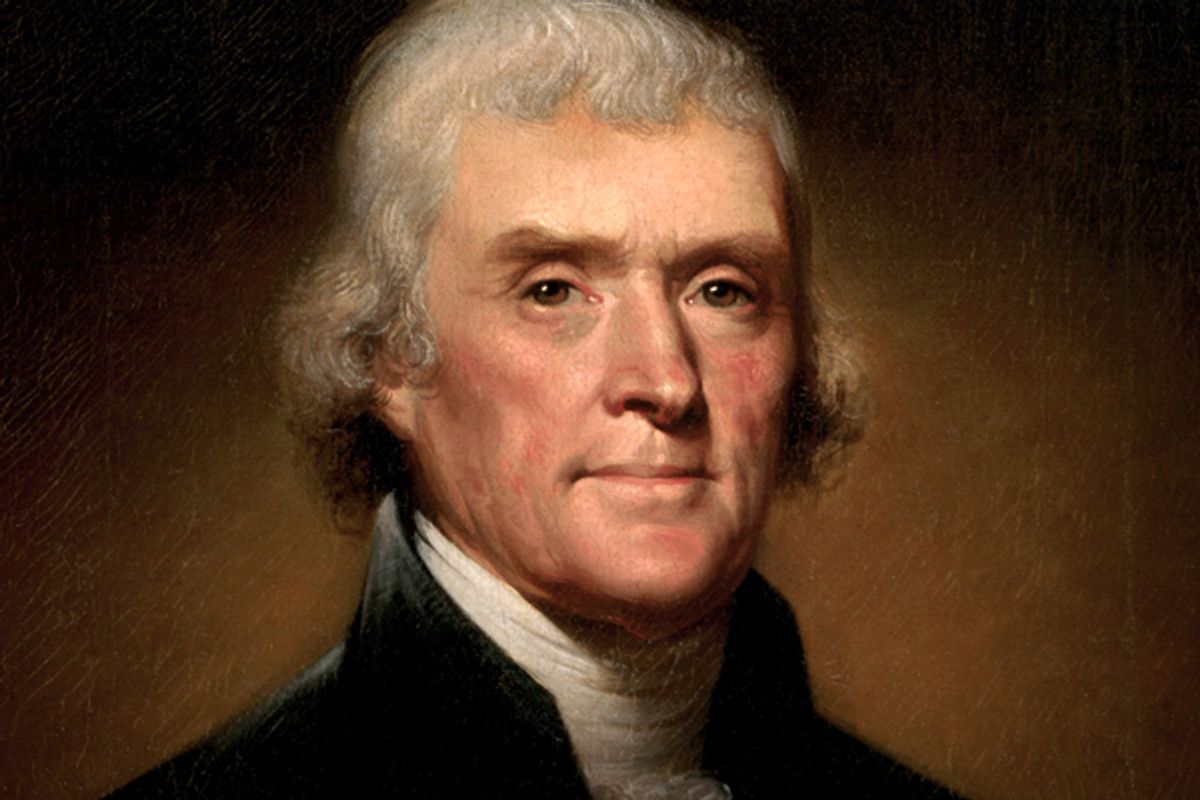

“The only security of all is in a free press.” Thomas Jefferson wrote these words to the Marquis de Lafayette at the age of 80. The reason Jefferson lauded a free press was that he wished, in tense political times, for the U.S. to function as a deliberative democracy, in which an increasingly better-educated citizenry monitored the policy decisions of its elected representatives and judged whether or not they deserved to remain in office.

A better-educated citizenry. That was Jefferson’s mantra, and it should be ours, too. Republicans in Congress have claimed Jefferson as their man, time and again quoting him as a champion of small government. One of their favorites lines is, “If it were possible to obtain a single amendment to our Constitution,” it would be “taking from the Federal Government the power of borrowing.” The Jefferson they do not pay attention to is the one whose lifelong dream was a well-funded public education system -- the Jefferson who spent his post-presidential retirement years creating a beautiful public university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Jefferson asked no less a figure than U.S. Attorney General William Wirt, notably the son of a Maryland tavern-keeper, to be its president. He understand that personal growth and national strength were best served by lifting up ordinary folks.

This week, the Senate debated student loan rates, which are now at a comfortable 3.4 percent and are set to double on July 1, if nothing is done. In his most recent college tour, President Obama focused on the endangered interest rate, fully aware that Republicans would have to support the Democratic initiative, if only to avoid embarrassment. Their sleight of hand was in proposing to come up with the $6 billion by removing money from preventive healthcare programs. That, then, is how the House Republican majority voted a week earlier to pass a one-year extension of the 3.4 percent rate. Democrats had urged cutting subsidies to oil and gas companies instead of raiding health care funds. When that wouldn’t fly, the alternative became an increase in the Social Security payroll taxes of the already wealthy. The White House vowed a veto after the House measure passed. It’s now the Senate’s turn. Congress will have to reach some sort of compromise, because neither party wishes to be seen as anti-student in an election year.

So, what about educational opportunity in America? Is it, or is it not, a priority? We all recognize that there is wasteful spending in the budget, but Republicans in Congress routinely recommend slashing funds for education, as though the fiscal crisis can be solved by cutting social programs first. (This past week, claiming that the Democratic plan was counterproductive, Senator Mitch McConnell, R-KY, relied on the fiction that government should not be “raising taxes on the very businesses we’re counting on to hire these young people.” He apparently views college graduates as dependents on government rather than future job creators.) Nothing could be more self-defeating, or hurtful to more people. Literacy programs? National writing projects? High school graduation initiatives?

They can talk all they want about Jeffersonian small government, but Thomas Jefferson stood for opportunity for young people, not a further consolidation of power among big business combinations. For millions of low- and middle-income students with admirable ambitions, a college education is the American dream. President Obama’s revelation that he and the first lady were only able to pay off their student loans eight years ago – they were in their forties – cannot but resonate with younger voters. On the campaign trail, Michelle Obama says that her husband was “the son of a single mother who struggled to put her son through school.” It’s a good narrative when you’re running against a candidate who was pretty much slotted for Harvard at birth.

Jefferson made himself quite clear. His definition of republicanism projected greater civic involvement and an expansion of the electorate, opening minds rather than opening the wallets of the privileged few to preserve their political sinecures. The Jefferson quote about a free press comes from a letter of November 4, 1823, addressed to his old friend Lafayette, the last surviving general to have commanded Continental Army troops in the American Revolution. Jefferson invoked his small government philosophy in the line that directly preceded his call for a free press: “A rigid economy of the public contributions, and absolute interdiction of all useless expences, will go far towards keeping the government honest and unoppressive.” And then, he assured, “the only security of all is in a free press. The force of public opinion cannot be resisted when permitted freely to be expressed. The agitation it produces must be submitted to. We are, for example, in agitation even in our peaceful country. For in peace as well as war the mind must be kept in motion.”

And how is the mind to be kept in motion? In a letter he addressed to a state legislator seven years before, as he proceeded with his design of the University of Virginia, Jefferson proposed that legislatures vote “a perpetual tax” to maintain a system of schools and a university “where might be taught, in its highest degree, every branch of science useful in our time and country.” Because, as he most eloquently put it, “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.” Yes, small-government champion Thomas Jefferson did not wish to tax citizens – except when the money was being used for public education.

Those of our time who would sacrifice opportunity for the young and shortchange students of all ages ought to heed the thought Jefferson expressed next. Taken out of context, or left to stand alone, it is a rallying cry for those who fear federal encroachment: “There is no safe deposit [for liberty] but with the people themselves,” he proclaimed. But the rest of his comment expresses the best Jefferson we know, the education champion. Liberty is never safe, he said, unless people possessed knowledge to make informed political choices; for, “where the press is free, and every man able to read, all is safe.”

Conservatives will certainly not appreciate one theory Jefferson put forward in the letter to Lafayette. He claimed that partisan ideologies were fixed in nature. Those of his day whom he labeled “Tory” or “aristocrat,” who wished to restrain the democratic rabble and keep the wealthy in charge, were, for Jefferson, “sickly, weakly, timid men” whose nerves could not withstand social change. Those who subscribed to his own, relatively liberal and open-minded belief in the educability of all (white) men were, he wrote, a “healthy, strong and bold” political interest.

Jefferson’s first priority was the intellectual elevation of those who were to succeed the founding generation -- those who would sustain the values of the Revolution. He opposed all profligate spending, but he championed education spending. And he embraced the free press as the republic’s clearinghouse of ideas and the instrument through which political and ethical progress was insured.

Shares