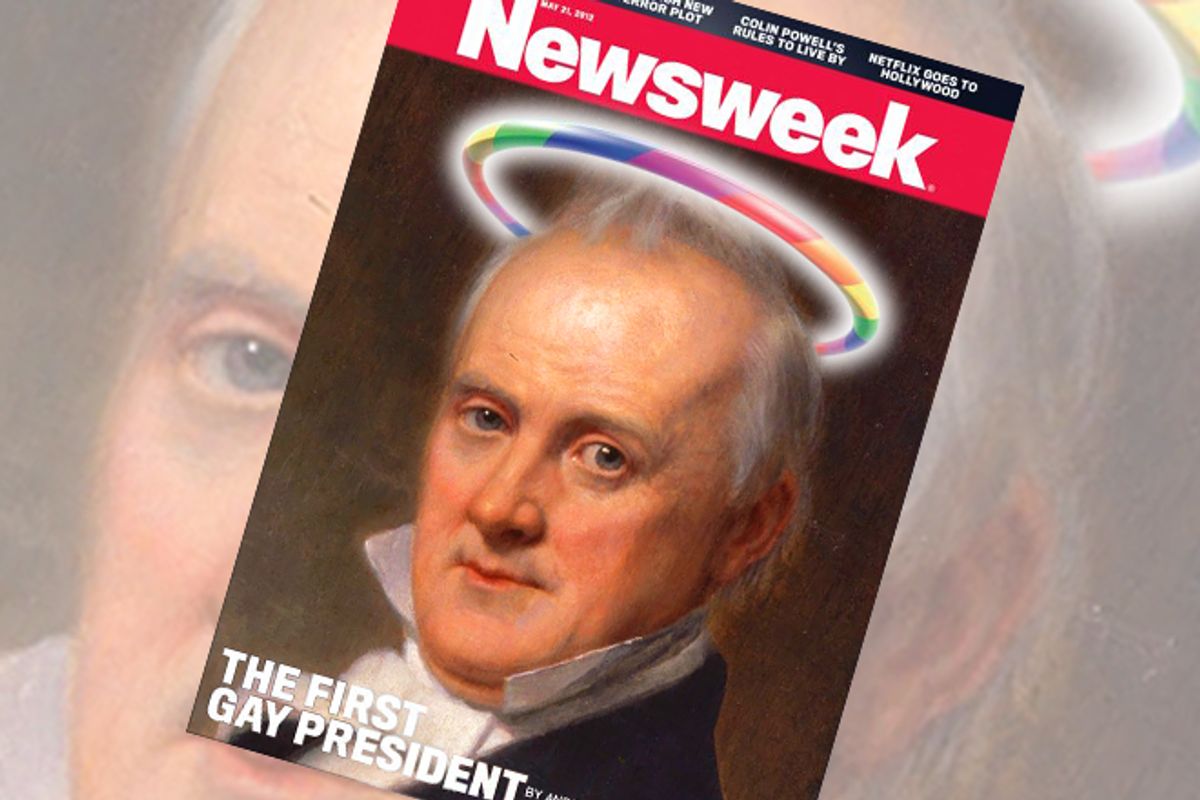

The new issue of Newsweek features a cover photo of President Obama topped by a rainbow-colored halo and captioned "The First Gay President." The halo and caption strike me as cheap sensationalism. I realize airport travelers look at a magazine for 2.2 seconds before moving on to the next one. I grant that this cover will probably get Newsweek a 4.4 second glance. I also understand that Newsweek is desperate for sales. Nevertheless, I doubt that the Newsweek of old, before it was sold for a dollar, would have pandered as shallowly.

The caption is a superficial way to characterize an important development of thought that the president -- along with the country -- has been making over recent years. It is also entirely wrong. Like the mini-furor a couple of months back about the claim that Richard Nixon was our first gay president, the story simply ignores that the U.S. already had a gay president more than a century ago.

There can be no doubt that James Buchanan was gay, before, during and after his four years in the White House. Moreover, the nation knew it, too -- he was not far into the closet.

Today, I know no historian who has studied the matter and thinks Buchanan was heterosexual. Fifteen years ago, historian John Howard, author of "Men Like That," a pioneering study of queer culture in Mississippi, shared with me the key documents, including Buchanan's May 13, 1844, letter to a Mrs. Roosevelt. Describing his deteriorating social life after his great love, William Rufus King, senator from Alabama, had moved to Paris to become our ambassador to France, Buchanan wrote:

I am now "solitary and alone," having no companion in the house with me. I have gone a wooing to several gentlemen, but have not succeeded with any one of them. I feel that it is not good for man to be alone; and should not be astonished to find myself married to some old maid who can nurse me when I am sick, provide good dinners for me when I am well, and not expect from me any very ardent or romantic affection.

Despite such evidence, one reason why Americans find it hard to believe Buchanan could have been gay is that we have a touching belief in progress. Our high school history textbooks' overall story line is, "We started out great and have been getting better ever since," more or less automatically. Thus we must be more tolerant now than we were way back in the middle of the 19th century! Buchanan could not have been gay then, else we would not seem more tolerant now.

This ideology of progress amounts to a chronological form of ethnocentrism. Thus chronological ethnocentrism is the belief that we now live in a better society, compared to past societies. Of course, ethnocentrism is the anthropological term for the attitude that our society is better than any other society now existing, and theirs are OK to the degree that they are like ours.

Chronological ethnocentrism plays a helpful role for history textbook authors: it lets them sequester bad things, from racism to the robber barons, in the distant past. Unfortunately for students, it also makes history impossibly dull, because we all "know" everything turned out for the best. It also makes history irrelevant, because it separates what we might learn about, say, racism or the robber barons in the past from issues of the here and now. Unfortunately for us all, just as ethnocentrism makes us less able to learn from other societies, chronological ethnocentrism makes us less able to learn from our past. It makes us stupider.

To think even for a moment about aspects of personal presentation other than sexual orientation forces us to realize that we today are not necessarily more tolerant. Consider facial hair. In 1864, with a beard, Abraham Lincoln won reelection. Could that happen nowadays? Is it mere chance that no candidate with facial hair has won the presidency since William Howard Taft -- and he wore only a mustache? Indeed, since Thomas Dewey in 1948 no major party candidate with facial hair has even run for president, and Dewey wore only the smallest of mustaches.

Perhaps the presidency is too small a sample. Let's add in the Supreme Court. Since 1930, 34 different men have served on the Supreme Court. All save Thurgood Marshall have been clean-shaven. (Lest readers think that Marshall's tiny mustache might topple this argument, let me point out that during most of the last 82 years, 70 percent of adult black males have had some facial hair, yet the only three African-Americans to have served on the Supreme Court or as president have had almost none.) The chance that a random sample of 33 white males would have had no facial hair is something like (.9)33 or about .03, not very likely.

"Even" today, many institutions, from investment banking firms to Brigham Young University, flatly prohibit beards on white males. Brigham Young falsifies its past to make this rule seem "natural." Its chief founder, John Maeser, usually wore a full beard and mustache. In front of the building bearing his name stands his bronze statue complete with full beard and mustache. In about 1960, however, perhaps earlier, BYU banned beards. Then in 1986, the university commissioned artist Ron Bell to paint a portrait of Maeser. Working from an old photograph, Bell did; of course, Maeser wound up bearded. So the administration asked him to remove the beard. "They didn't want today's students to believe they could follow suit," in the artist's words. He complied.

If this example seems too religious, consider the huge secular company Walt Disney Enterprises. The last time I visited Disney World, it still banned facial hair, although it quietly made exceptions for African-Americans with well-trimmed beards or mustaches.

In themselves, beards may not be signs of progress, although mine has subtly improved my thinking. Nevertheless, we reached an arresting state of intolerance when the Disney organization, founded by a man with a mustache, would not allow one even on a janitor. Moreover, before we trivialize these examples by thinking they apply only to facial hair, consider that Lincoln was also our last president who was not a member of a Christian denomination when taking office. Could a non-Christian like Jefferson or Lincoln be president today? It's not clear.

All that said, President Obama's change of heart about gay marriage remains significant. It does show increasing tolerance compared to our recent past. During the nadir of race relations, that terrible period between 1890 and about 1940 when white America went more racist in its thinking than at any other time, the U.S. also clamped down on beards, liquor (briefly) and, yes, homosexuals. As Jackie Robinson was not the first black player in Major League Baseball, but rather the first after the nadir, so President Obama is not our "first gay" president (Forgive me: I cannot seem to retype Newsweek's silly headline without putting quotation marks around the words), but only our "first" since the nadir.

Remembering that James Buchanan was homosexual complexifies our national narrative, to be sure, but it is a complexity that we need. It prompts us to remember that terrible era, the nadir, when we all moved backward, not just the South. Not just organized baseball but also the Kentucky Derby, the NFL and even previously "black" jobs like railroad foremen got redefined "white only." Communities across the North became sundown towns, barring African-Americans formally or informally. Even North Dakota outlawed interracial marriage.

Forgetting Buchanan's sexual orientation helps us forget all the other national secrets we have packed into that closet with him. Ultimately, it prompts us to succumb to chronological ethnocentrism. If, however, we can rid ourselves of the fantasy that we are always getting better, then maybe we can create a nation that actually becomes more tolerant. Then we might -- again -- elect a real gay president. After all, just three months ago, Disney started letting white male employees grow beards.

Shares