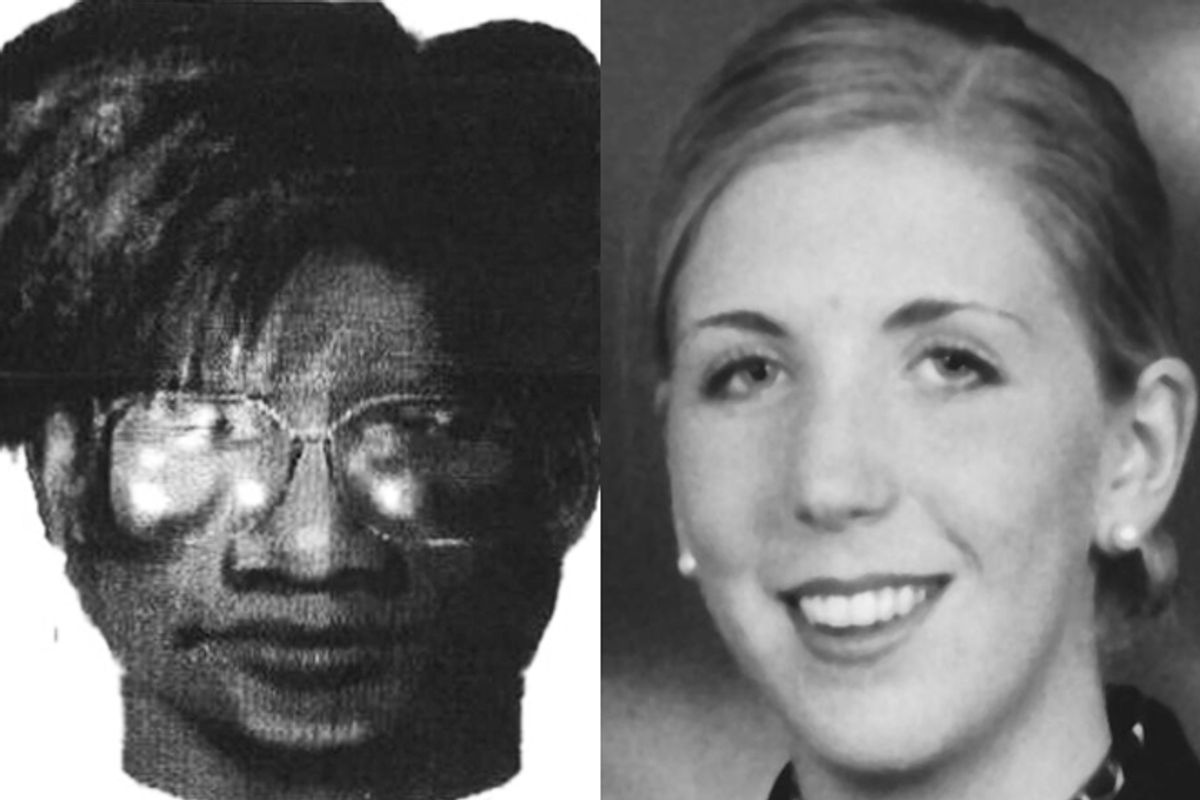

Lucie Blackman, 21, went out for the afternoon in 2000, phoning her roommate and best friend Louise to arrange a meeting later that night. Lucie never showed up, and within a few days she'd become one of those vanished blondes whose fates fuel headlines and hours of speculative media coverage. She was British, a former flight attendant, and she and Louise were living in Tokyo. They were also bar hostesses, a profession with a very specific meaning in Japan, difficult to explain to foreigners and not entirely clear to the Japanese themselves. Lucie both did and didn't match the classic Missing Blonde profile, and for a while the mystery of what happened to her threatened to lapse into permanent obscurity.

One thing made a difference: The actions of Lucie's father, Tim Blackman, who arrived in Tokyo to join his other daughter, Sophie, in publicizing the search and prodding the police. Richard Lloyd Parry, Tokyo bureau chief for the Times of London, covered the case as it unfolded, first over the course of several months while Lucie's whereabouts and abductor remained unknown, and finally for the six years it took to try the man accused of killing her, Joji Obara. The book Parry wrote about the case, "People Who Eat Darkness," is an exceptionally perceptive and nuanced look at a terrible crime, one that put nations, institutions and family members at odds, and often into bitter and toxic conflict.

Unlike Truman Capote, author of "In Cold Blood," the most celebrated true crime narrative of all, Parry is in essence a reporter; this is no "nonfiction novel." But like Capote, he's less interested in dishing the eerie or lurid details than he is in exploring the penumbra of the crime, the complex factors that fed into it and the unpredictable effects it had on an ever-spreading network of people. The true crime genre has a (mostly well-earned) reputation for trashiness, but it fascinates for legitimate reasons, as well. Transgression, justice and punishment speak to the very heart of what a society is, how it holds its people together and how they decide who lies beyond the pale.

Because Lucie Blackman was a foreigner, and one employed in an industry that the Japanese view as disreputable, the Tokyo police were inclined to dismiss her disappearance. Bar hostesses get paid to talk to and flirt with customers, and they are expected to go on (paid) dinner dates with them outside the clubs where they work, but it's an arrangement that usually stops short of actual sex. Nevertheless, the Japanese think of most foreign hostesses as irresponsible, drug-loving backpackers who might well run off without telling anyone or get mixed up with dangerous people. Whether or not a Westerner would call what bar hostesses do a part of the sex industry, for the Japanese, these women belong to that category of "bad" girl who can expect little help or concern from authorities should she get into serious trouble.

Crime is not what it was in Capote's day. In addition to finding and building a case against the perpetrator -- jobs for law enforcement authorities -- there's handling the media, a task usually left to the victim and his or her relatives. Lucie's father proved, initially at least, to be a master at this. Tim could detach himself emotionally from the horror of his situation and strategize. He was able to capitalize on a G-8 summit meeting being held in Japan around the same time Lucie vanished and parlay it into the intervention of British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Blair publicly asked Japan's prime minister to front-burner the investigation, and met with Tim and his younger daughter Sophie while he was in Tokyo.

The police, who had been dragging their heels on Lucie's disappearance, found this development (which made perfect sense in the political context of Britain) flabbergasting. Still, it worked: Lucie, who might have been written off as one of those "disposable" women of dubious virtue, was conclusively cast as an innocent girl, "naive perhaps, out of her depth," but an adventurous daughter rather than a reckless slut. Tim was driving the narrative, as an electoral campaign manager might put it, and he was good at it. He liked talking to the press, even the tabloid press, and they liked him.

But if Tim was good at telling Lucie's story, he was less successful at telling his own. Some of the most penetrating passages in "People Who Eat Darkness" concern what Parry refers to as the "script" expected from bereaved parents. Years later, Parry covered a press conference given by the father of another murdered girl and recognized in him "everything the world expected of a man in his situation: broken, helpless, turned inside out by loss."

Tim, however, was composed, which aroused a formless popular suspicion regarding his sincerity. In similar cases, this uneasiness frequently takes the form of outside observers suddenly deciding that the parents might be implicated in their child's disappearance or death. Tim, halfway around the world when Lucie vanished, was immune to that, but when he quarreled with the rich businessman funding the private search for his daughter, accusations of self-interest and even exploitation surfaced.

Lucie's mother, Jane, on the other hand, behaved exactly as a grief-stricken mother is supposed to. In some respects, the truth about her parents' failed marriage is as unknowable as the events of Lucie's final hours. Unamicably divorced, Tim and Jane avoided even being in the same room together throughout the crisis. Was Jane, who seems to fall for every kind of supernatural hokum that crosses her path, pathologically vindictive, or was Tim as big a shit as she claimed? Just when you think you've made up your mind on that question, a new development comes along to knock you into the other camp.

As for the perpetrator himself, he remains something of a cipher to Parry, who was never able to interview him. Obsessively camera shy, Obara deftly avoided being properly photographed even after his arrest. He was clearly demented, as a long, self-justifying self-published book (disguised as the work of concerned supporters) amply demonstrates. Resolutely confident and unrepentant, Obara was also utterly unlike the vast majority of Japanese criminal defendants. (Parry explains that the justice system there depends almost completely on the ability of police investigators to shame suspects into confessing.) They simply didn't know what to do with him. The Japanese blamed Obara's recalcitrant behavior on his Korean ethnicity.

The Blackmans and Obara, Western-style players, descended on a criminal justice system unprepared to cope with them. "The inadequacy of its police force is one of the mysterious taboos of Japanese society," Parry writes, "a subject that the media and politicians strain to avoid confronting, or even acknowledging." The blunders of the police were many, but they could also be dogged investigators. Their real problem, according to Parry, is that they are good at dealing with "conventional Japanese criminals," but when faced with the unexpected, they're "sclerotic, unimaginative, prejudiced and procedure-bound."

Obara behaved like a British or American criminal -- taking charge of his defense, actively contesting the prosecutors, formulating a counternarrative to account for Lucie's death. Watching how Japanese institutions responded to him, as well as to the Blackmans' efforts to influence the investigation, proves fascinating. Since true crime, at its best, serves as a window on what a society cares about -- how it constitutes not only what's right and wrong but what's sympathetic, reasonable, acceptable and important -- the Obara trial was a most illuminating culture clash.

Parry doesn't, however, forget what lies at the root of this drama: the death of a young woman who, whatever her doubts or flaws, had every reason to hope for a wonderful life. As the investigation would eventually reveal, this tragedy was eminently preventable. The people who tried to tip off the police about Obara were dismissed as not worth listening to. Let's hope they're not the only ones to learn from that mistake.

Shares