Memory is evanescent. I can’t recall where I made the purchase; perhaps it was during an elementary-school or Cub Scout trip. Nor do I remember my exact age; it was anywhere between 8 and 10. What I do remember vividly is the visceral experience: the feel and smell of the paper as I unfurled it. The sense that I was both witnessing and experiencing history, which I then held tangibly in my hands. In the morning of that day, my mother had given me some small change for the day's trip, and I spent it on a reproduction of the Declaration of Independence. It was printed on a rough-hewn, yellow paper stock with stains on both sides, and it had a rigidity that made it hard to open (it was folded in quarters). The reproduction possessed a distinct smell, and the texture was coarse, as if it was once damp and left to dry. “Onion paper,” my mother explained when I got home. It sounded exotic. Sadly, I've forgotten the whereabouts of that formative piece of paper, but the power of the experience has remained.

Memory is evanescent. I can’t recall where I made the purchase; perhaps it was during an elementary-school or Cub Scout trip. Nor do I remember my exact age; it was anywhere between 8 and 10. What I do remember vividly is the visceral experience: the feel and smell of the paper as I unfurled it. The sense that I was both witnessing and experiencing history, which I then held tangibly in my hands. In the morning of that day, my mother had given me some small change for the day's trip, and I spent it on a reproduction of the Declaration of Independence. It was printed on a rough-hewn, yellow paper stock with stains on both sides, and it had a rigidity that made it hard to open (it was folded in quarters). The reproduction possessed a distinct smell, and the texture was coarse, as if it was once damp and left to dry. “Onion paper,” my mother explained when I got home. It sounded exotic. Sadly, I've forgotten the whereabouts of that formative piece of paper, but the power of the experience has remained.

[caption id="attachment_327361" align="aligncenter" width="492" caption="As I remember it. Every defect was a hidden treasure."] [/caption]

[/caption]

Around that same time my father came home with a present for me. It was a ream of blank newsprint paper. He was a transit worker, and he explained that someone had left it behind on the subway. For me it became a treasured gift, as the paper looked exactly like the paper of the comic books I so fervently read. With the paper as my narrative canvases, I began producing my own comics by the score: Dr. Sol, The Crusaders, The Saturator, Gas-Man! et al.

[caption id="attachment_327551" align="aligncenter" width="492" caption="Page from The Saturator, created when I was 11. At long last, I could produce comic books that looked like comic books."] [/caption]

[/caption]

Cut forward to 2001 when I first began to go through the Woody Guthrie Archives, located in Manhattan, to explore whether it was possible to make a book of his artwork. (It was.) Peering through his drawings and journals, I had the same experience I had as a child, although this time the documents had authentically aged: The years had added a yellow patina to many of these pieces, despite the fact that they were stored in a climate-controlled environment. This was the first time I was confronted with the question of how best to reproduce this work. Does one attempt to imagine it as it was when originally created, with pristine white backgrounds and colors that have not yet faded? Or reveal it as it exists today, less vivid but with the stains of time present? Since the former was impossible to know, I came to the conclusion that only the latter made sense.

I experienced this again a few years later with Louis Armstrong’s collages, which he “laminated” with Scotch tape. With these collages there was no question about heading back in time—the dried tape was as much a part of the collages as every photo was.

[caption id="attachment_327411" align="aligncenter" width="492" caption="Woody Guthrie’s journals gain gravitas with the patina of passing years."] [/caption]

[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_327481" align="aligncenter" width="492" caption="In Armstrong’s collages, yellowing tape adds to the experience."] [/caption]

[/caption]

Which brings me back to comics. One of the first collections I ever purchased, in the 1980s, was Bill Blackbeard’s oversize "Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics," first published in 1977. Within the anthology, "Hogan’s Alley," "Little Nemo in Slumberland," "Gasoline Alley," "Buster Brown," and myriad others were lovingly and photographically reproduced with great detail on a paper stock closely akin to newsprint.

Imagine my surprise when I began to explore hardcover anthologies of comic books from DC and Marvel, released in the same era. "DC Archives" and "Marvel Masterworks" could not have been more different from Blackbeard’s groundbreaking accomplishment. They were garishly colored on high-gloss white stock; I had the sensation that I would need sunglasses to read them. I soon learned that since the original comics were unavailable—as were photostats—and the original artwork had been lost, destroyed, or scattered, the reproduction involved hiring present-day artists to trace and recolor the comics. The final effect was not so much of a black-and-white MGM classic colorized by Turner but rather like Gus Van Sant’s frame-by-frame remake of "Psycho," starring Vince Vaughn as Norman Bates.

[caption id="attachment_327541" align="aligncenter" width="492" caption="A page from Bill Blackbeard’s seminal work on newspaper comic strips, beautifully photographed in the pre-scanning days."] [/caption]

[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_327501" align="aligncenter" width="492" caption="A side-by-side comparison of the original Fantastic Four #4 comic and a Marvel Masterworks “recreation.” Not only are the tracings inaccurate, the coloring does not adhere to the original."] [/caption]

[/caption]

The first time I became aware that change was in the air was when DC released "Jack Kirby’s Fourth World Omnibus, Vol. 1. "Here, an off-white paper replicated the look and feel (although happily not the fragility) of newsprint, and the line art was reproduced from the original stats. Fortunately, DC has employed this technique for other releases, although Marvel has opted for the strategy of tracing and reproducing on bright paper.

Smaller publishers like Fantagraphics followed Blackbeard’s lead, and since the advent of digital scanning, many others have chosen similar tacks: Abrams, IDW, Dark Horse, Titan, and Yoe Books all beautifully reproduce from the source. Still, two schools of thought have emerged about how best to achieve an optimum reading experience, both utilizing matte paper. One approach keeps the yellowing borders intact, while the other involves removing the borders and enhancing the colors, as if the comics had originally been printed on white, higher quality stock.

[caption id="attachment_327531" align="aligncenter" width="492" caption="The DC release Jack Kirby’s Fourth World Omnibus, Vol. 1, successfully replicates the look and feel of the original comics."] [/caption]

[/caption]

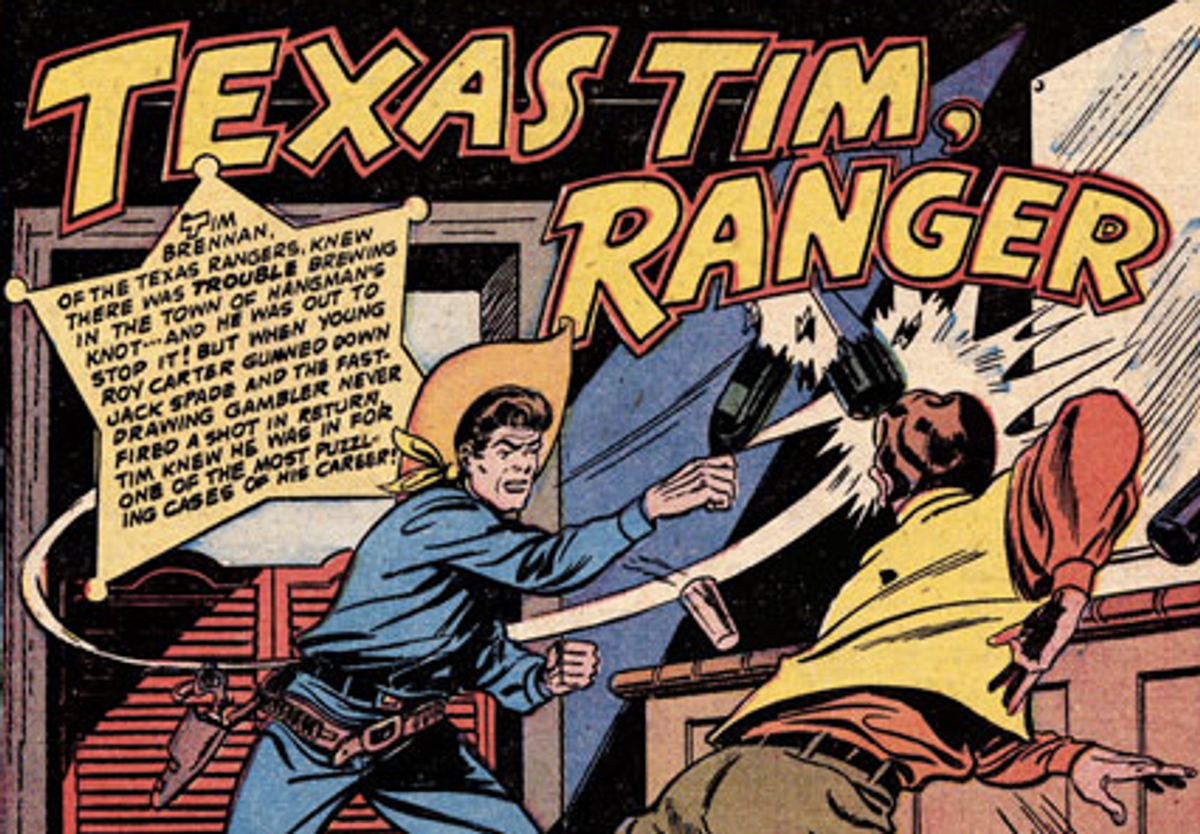

In the next month, two books of comics reprints I've edited will be released, showcasing both techniques. "Golden Age Western Comics," published by powerHouse Books, reproduces the original pages whole cloth, although the blacks and colors have been enhanced to replicate how they would have appeared before fading. In addition, we made minor touch-ups. Up until this point, this generally would have been my preference, as I prefer the viewing experience to be as close to reading a 60-year-old comic as possible; these comics were never printed on white paper to begin with. However, Fantagraphics has removed the borders and all signs of aging on our Mort Meskin book of reprint stories, "Out of the Shadows." Comparing the two releases, I've come to appreciate the advantages of both approaches. As a genre, Westerns are mired in nostalgia, having long since been replaced by other action tropes in modern-day entertainment. With that in mind, a book as object set in a distant time and place seems appropriate. For the Mort Meskin collection, we hoped that a contemporary audience would rediscover him; Fantagraphic’s fresh, newly minted approach goes a long way toward achieving that.

[caption id="attachment_327461" align="aligncenter" width="492" caption="A page from Golden Age Western Comics, published by powerHouse."] [/caption]

[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_327521" align="aligncenter" width="492" caption="A page from Out of the Shadows, released by Fantagraphics."] [/caption]

[/caption]

Shares