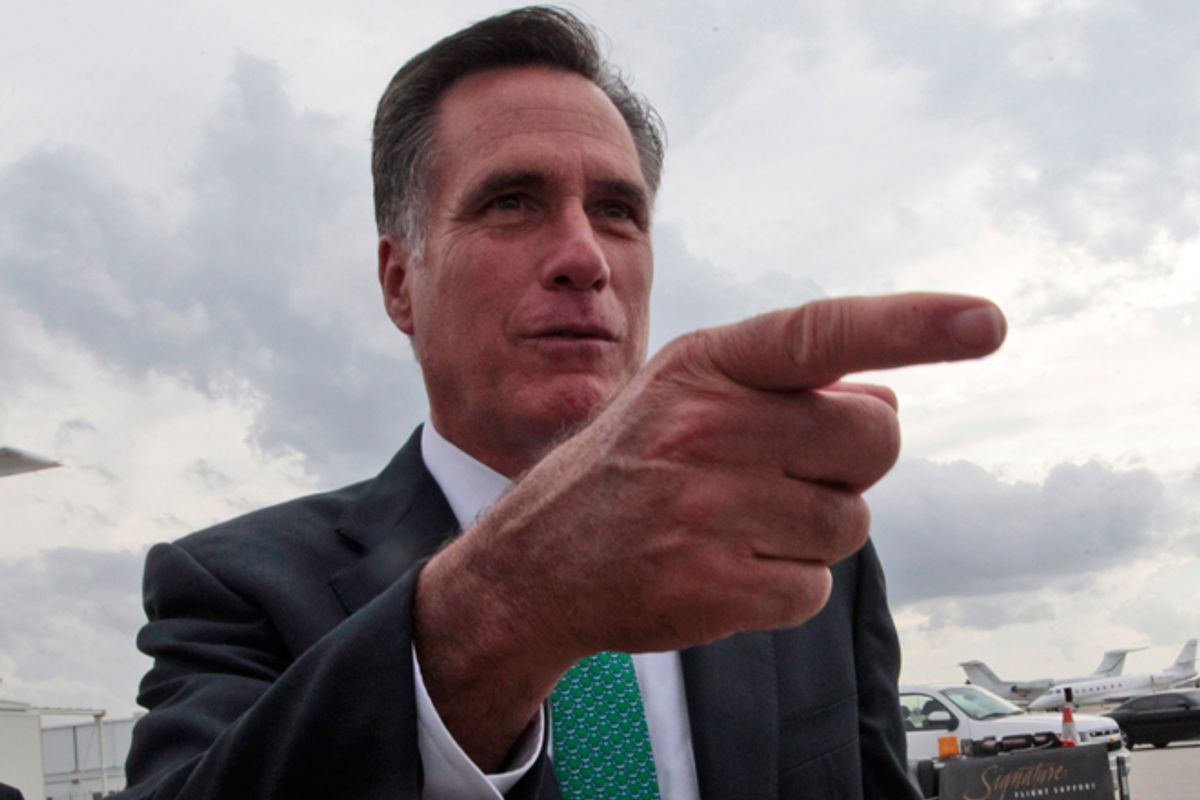

Nearly two months after he began sporting the title “presumptive Republican nominee,” Mitt Romney is poised to cross the magic 1,144-delegate threshold in Texas today. In terms of the current campaign, it’s a ho-hum milestone; the political world’s attention long ago shifted to the Romney/Obama general election fight. But take a step back, and the circumstances are a bit more remarkable.

After all, it was almost exactly one year ago that another development in Texas seemed to put Romney’s nomination prospects in grave danger: Rick Perry’s unexpected May 27, 2011, announcement that he was considering jumping into the race.

This came at the end of a month in which Romney’s supposed "healthcare problem" dominated coverage of the race, with the candidate using a speech at the University of Michigan to plead with Republicans that they not consider his Massachusetts law as the blueprint for ObamaCare. Early polling wasn’t encouraging; already Romney had been (briefly) lapped by Donald Trump, and now Herman Cain was making a move. The only thing keeping Romney in contention, conventional wisdom held, was the lack of a truly credible alternative – someone ideologically acceptable to the base but with a resumé weighty enough to satisfy party leaders. Perry, the third-term governor of the nation’s second-largest state, seemed like he might fit the bill.

That Romney overcame this can, of course, be attributed to Perry’s utter incompetence as a communicator. When Perry finally entered the race in August, he immediately opened a large lead over Romney and – and unlike, say, Cain – had an opportunity to cement it by uniting the party’s opinion-shaping class behind him. But Perry’s trainwreck debate performances scared those Republicans away and hastened his demise.

But it’s also true that Romney was actually fairly well-positioned at this time last year. Healthcare was never that big of a problem for him, since it was simply the idea of ObamaCare – and not any of the particulars of the actual law – that enraged the GOP base. This allowed Romney to rail against ObamaCare while spouting gobbledygook to claim that he’d done something completely different in Massachusetts. If he’d defended the federal law for some reason, Romney would have been giving away the nomination, but he knew better than to do that.

The other advantage Romney enjoyed, as Seth Masket points out, has to do with the Tea Party-era evolution of the definition of conservatism. The policy positions that the right now demands were relegated to the fringes just a few years ago – meaning that there really never was going to be an alternative to Romney who was both ideologically pure and credible as a national candidate. Even Perry, as it turned out, had some ideological baggage. And besides Perry, Romney only had to fend off candidates that party leaders were never interested in lining up behind – Cain, Newt Gingrich, Rick Santorum, Michele Bachmann.

This doesn’t mean the nomination was in the bag for Romney the whole time. Perry was a legitimate threat (and Tim Pawlenty perhaps could have been one, had he shown any life on the trail), and a major chunk of the GOP base – white evangelical Christians, especially in the South – remained resistant to Romney even as it became clear he’d be the nominee. But the predictions of his imminent demise that popped up throughout 2011 seem a bit foolish now.

Is there a lesson here for the next time around, even given the odd circumstances and candidate roster that defined the 2012 GOP race? Maybe it’s this: If a front-runner seems wounded and vulnerable, don’t write him or her off until there’s a truly credible alternative on the stage.

Shares