What does a good crime novel do? At the very least, it must lure its reader into the classic rhythm of transgression and retribution, mystery and solution. You want to know what happened, as well as what happens next, and you want the ending to feel resolved or satisfying. As a matter of fact, sucking you into caring about those things is all a crime novel really needs to do to be good. It can also offer zingy prose or nuanced characters or a foray into an interesting social milieu, but it doesn't have to. The bar is not necessarily high.

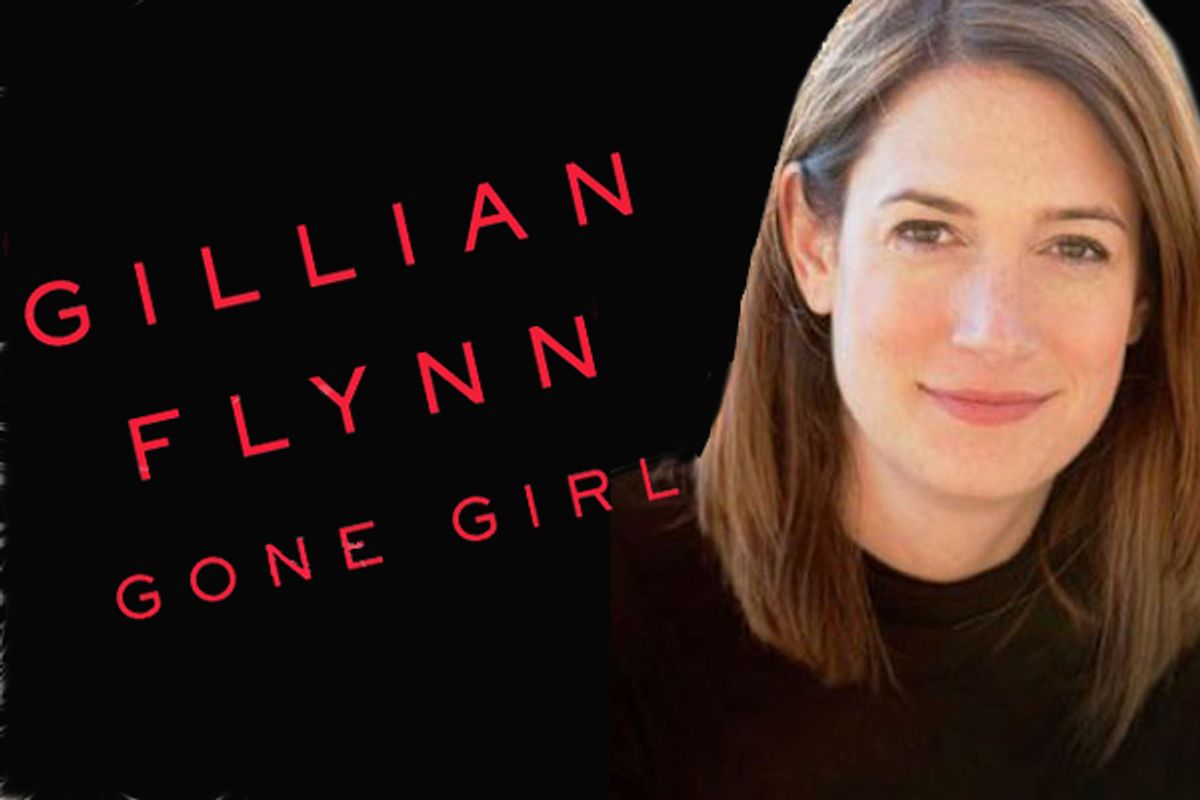

A great crime novel, however, is an unstable thing, entertainment and literature suspended in some undetermined solution. Take Gillian Flynn's "Gone Girl," the third novel by one of a trio of contemporary women writers (the others are Kate Atkinson and Tana French) who are kicking the genre into a higher gear. Flynn's particular specialty is "unlikable" narrators: Not freakish killers, but ordinarily selfish, resentful or sarcastic types, the kind of characters that readers often seem to dislike because they offer an uncomfortable reflection of their own mundane shortcomings. (More traditional crime-novel heroes have flaws, of course, but only noble ones, like caring too much about the case, losing their tempers in the face of injustice or failing at department politics.)

"Gone Girl" has two such narrators, the halves of a broken marriage: Nick Dunne and his wife, Amy. Nick comes home on the day of their fifth anniversary to find their suburban house tossed and Amy vanished. His account of the unfolding media circus following his wife's disappearance alternates with excerpts from Amy's diary, in which she describes how they met as two young magazine journalists in New York and how they ended up, miserable and estranged, in North Carthage, the economically depressed Missouri town where Nick was born and raised.

And the novel has two mysteries: What happened to Amy, and what happened to Nick-and-Amy? Why does this marriage, or any marriage, fall apart? Was it external pressures? Both partners lost their media jobs thanks to the Internet-enabled mentality that Nick describes as "free is better than good." Or is it that they've taken each other for granted? Both husband and wife have totted up lists of slights, oversights and grievances, most of which result from inattention. Their anniversary tradition is a case in point: Every year, Amy devises an elaborate treasure hunt in which the clues, to her mind, celebrate the highlights of their relationship. Nick sees these games as quizzes that he will inevitably fail. The real subject?: "What is my wife thinking? What was important to her this past year? What moments made her happiest? Amy, Amy, Amy, let's think about Amy."

As for Amy herself, her diary reveals a woman whose wit is both excitingly barbed and a bit scary. Before meeting Nick, she recounts going "to endless rounds of parties and bar nights, perfumed and sprayed and hopeful, rotating myself around the room like some dubious dessert." Later, she indulges in a hilarious diatribe about the "Cool Girl," a mythical creature who "adores football, poker, dirty jokes and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex," and who only really exists in "movies written by socially awkward men." For his part, and however clueless he claims to be, Nick has a pretty shrewd take on why his New York–raised wife feels so out-of-place in his hometown, where "the women shop at Target, they make diligent, comforting meals, they laugh about how little high school Spanish they remember." For the competitive Amy, this is purgatory: "A town of contented also-rans."

For the first half of the novel, these two contradictory yet strangely harmonized accounts of the marriage's decay command most of the attention. It's a mercilessly observant portrait of contemporary romance, one that might have been written by Jonathan Franzen or Jeffrey Eugenides -- except for those dodgy moments in Nick's narrative where he fails to explain who keeps calling him on that disposable cellphone. Flynn, a former staff writer for Entertainment Weekly, is especially good on the infiltration of the media into every aspect of the missing-person investigation, from Nick's cop-show-based awareness that the husband is always the primary suspect to a raving tabloid-TV Fury who is out to avenge all wronged women and obviously patterned on Nancy Grace.

You couldn't say that this is a crime novel that's ultimately about a marriage, which would make it a literary novel in disguise. The crime and the marriage are inseparable. As "Gone Girl" works itself up into an aria of ingenious, pitch-black comedy (or comedic horror -- it's a bit of both), its very outlandishness teases out a truth about all magnificent partnerships: Sometimes it's your enemy who brings out the best in you, and in such cases, you want to keep him close.

Shares