Trust me on this: There is a reason digital rhymes with douchenozzle. Almost rhymes. Whatever. The point is, scoff not at analog, nor the archaic structuring of sentences. Some things were improved upon until perfected. Others were perfected, then “improved upon.” In the former category would be your evolutionary biology, your professional basketball strength-training regimens, your automotive safety laws.

In the latter, vinyl records. And newspapers. (I don’t have room to talk about both, so with a special Father’s Day shout-out to Charlie Mansbach, front page editor and institutional memory of the Boston Globe, I’m going to focus on vinyl.)

To capture sound is to isolate a moment, canonize it, enter it into the historical register. The genius of vinyl is that it allows – commands! – us to put our fingerprints all over that history: to blend and chop and reconfigure it, mock and muse upon it, backspin and skip through it. Vinyl spins like the earth on its axis, the planets around the sun, the hands of a clock. Unspools like time itself. Our ability to control it symbolizes a power greater than any we have over our own lives.

Look closely, and you can see where the grooves of a record widen, indicating a sparseness that can only be a bass solo, or grow denser to accommodate a cresting density of sound. The studious observer can read a record as one reads the face of a lover: Seeing everything and nothing at once. He can drop the needle on the drum break with the precision of a surgeon making an incision. If he has two copies of the record, and two turntables, and sufficient manual dexterity, he can alchemize the incidental into the infinite, extend the groove for as long as anybody cares to get down. In Vonnegut’s "Slaughterhouse Five," humans (though they don’t know it) can reproduce only if five aliens participate, unseen, in the sex act. So it is with vinyl. We broker the couplings, manipulate the genetics of the offspring. But we are merely ghosts, seeking a way back into an act of creation that has already been closed to us.

Vinyl is democratic, as surely as the iPod is fascist. Vinyl is representational: It has a face. Two faces, in fact, to represent the dualism of human nature. Vinyl occupies physical space honestly, proud as a fat woman dancing. Shelves bow beneath its weight. Digitized music marches in single file to disguise its numbers. It’s easy to spot a DJ who did not cut his teeth playing records, who has always had 50,000 songs on his laptop and has thus never negotiated the glorious parameters vinyl’s bulk imposes. Who has never spent hours poring through a collection before a gig, figuring out how to cram six hours of music into two milk crates, mentally building set lists, reading a crowd yet unassembled. You can spot him because he sucks. His sets lack logic and flavor, conviction and shape. Remember how before we all had cellphones, we’d make plans and stick to them, and this lent a certain structure to our lives, forced us to be where we said we’d be and to know where we were going ahead of time? No? How old are you, anyway?

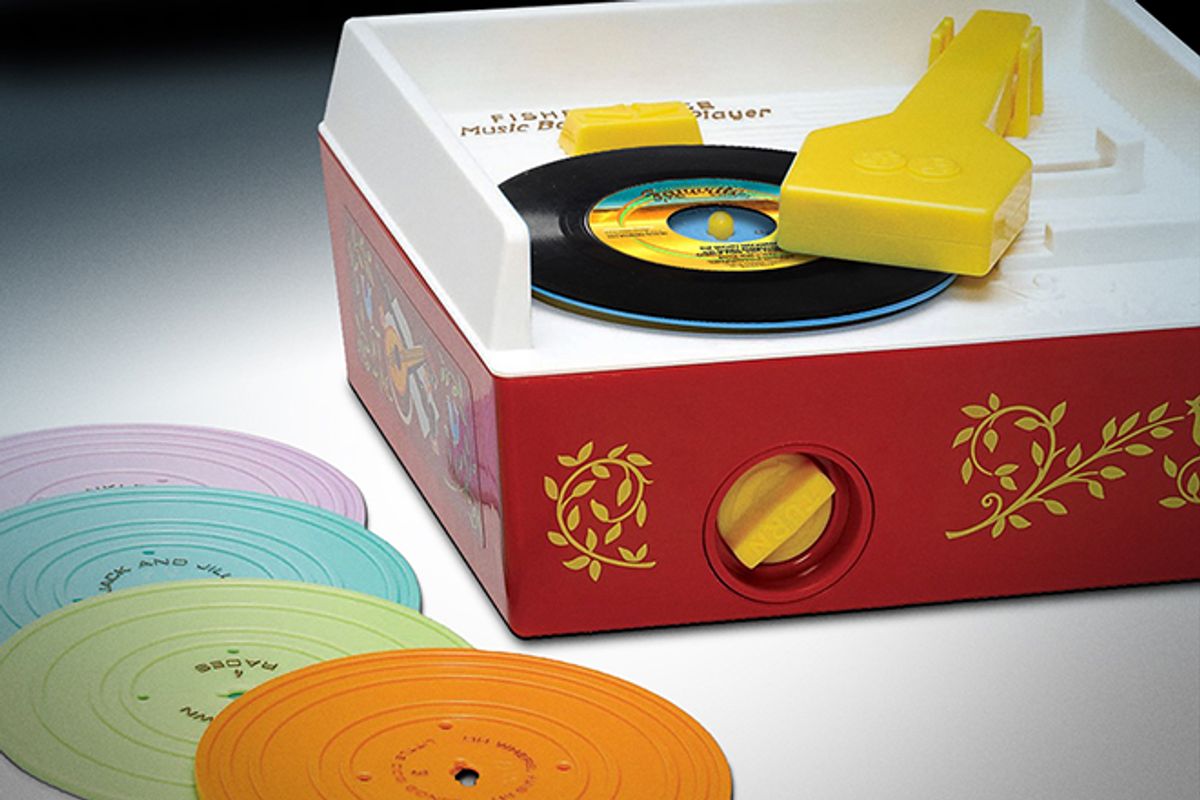

Vinyl accepts the ravages of nature – embraces its own frailty, as we all must. Sun warps it. Turbulence disturbs it. Ill treatment scars it, for life. It’s intensely tactile. That’s important. Have you ever seen that YouTube clip of a baby trying to turn the page of a book by running two fingers across it over and over because he thinks it’s some kind of screen, the poor schmuck? That’s pretty much the opposite of introducing a kid to music by teaching her how to flip through a stack of LPs, recognize the platter she wants, remove it from the cardboard cover, place it on the deck, lay the needle on the groove, and hit the play button.

Vinyl does not accept the verb “buy.” “Buy” is for pedestrian transactions, for goods and services that are readily available: tomatoes, deep tissue massages, treasury bonds. You “dig” for vinyl, or “come up on” a record. Vinyl is never new, always used; how and by whom and to what end, we’ll never know. It turns us into archaeologists, historians, mystics; we attempt to date it, divine its worth, anticipate its content. To spend extravagantly on a rare treasure is honorable. To drop so much as a dollar on an unworthy joint is to wreath oneself in shame.

What are we looking for, as we ransack our uncles’ attics and squat uncomfortably over thrift store bins? The record god Afrika Bambaataa claimed it was “the perfect beat,” but really it is what we’re always seeking: ourselves. Our heritage, our legacies. Artifacts of better times and distant lands and the stupefying diversity of mankind’s sonic output. No matter what we find, we continue to look.

Or, to put all this rhapsodic shit in simpler terms, what would you rather leave your kids when you die? A roomful of records, or a Pandora station?

Shares