My siblings and I have a hard time on Father’s Day. It reminds us that the anniversary of our dad’s murder is around the corner: July 7, 1993. I was 22 when he died, shot by strangers in his basement, and every year we wrestle with how to honor his complicated memory. Lately, we can’t even agree if he was a man, let alone our father.

I fought with my sister about this two years ago on Father’s Day, when I was back home in Seattle visiting her. We avoided the topic all day, until she came home in the wee hours from her bartending job at a gay bar.

“I was talking with Jean tonight about Dad,” she said. Jean was one of her transgender customers. “And Jean said, ‘Maybe you were never meant to celebrate Father’s Day, because your dad was always meant to be a woman.’” She looked at me as though this might be a consolation, but I was having none of it.

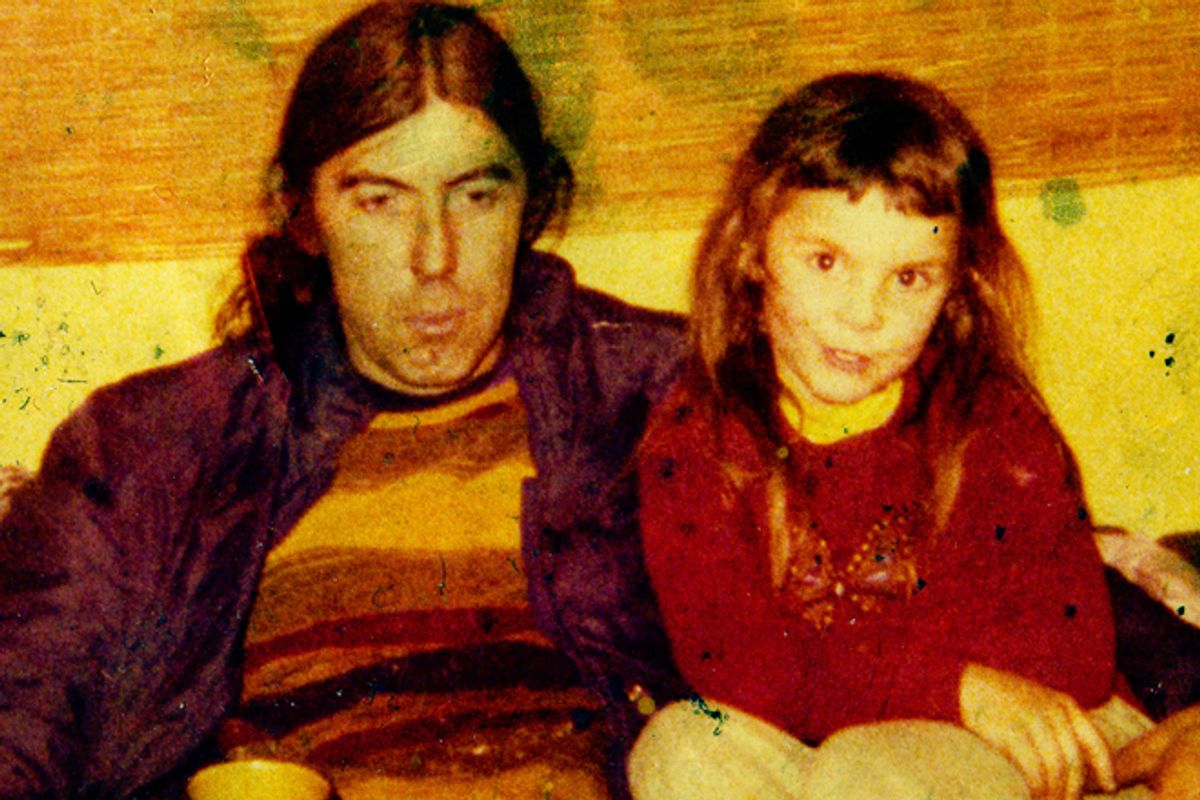

“That’s absurd!” I said, because I believe our dad was a man through and through. He was 6-foot-7. He was lanky, deep-voiced. I often described his personality as somewhere between Anthony Bourdain and Howard Stern. What was most damning, in my mind, was how physically abusive he was to my mother and me. Bridgette missed much of this. She was 5 when I went into foster care at 15. The court made my dad take anger management classes after that. “He was always talking about how he hated women,” I said. “If that’s the case, how could he have really been one?”

Bridgette closed her mouth, and refused to open it again. The topic was too loaded. We didn’t speak a word about it for the rest of the trip.

My father decided to get a sex change shortly before his murder. He had been a cross dresser as long as I could remember, but he always kept his “dress-up times” -- as my mother and I referred to them -- confined to the house. Though he went by Tom usually, during these interludes, he insisted we call him “Tommy.” By day he worked male-dominated professions: He owned a tree removal company, which required him to wield chainsaws. When business was slow, he drove a cab. At night he would come home and transform into Tommy, but not every night. He could go for nights, weeks, months without dressing up. In the late '80s, when I went into foster care, he stopped for several years completely.

Then the '90s hit: RuPaul was in vogue, and gay pride went mainstream. It seemed like everyone was coming out of the closet. I had been away from home for five years, living in California, going to Scripps, a small private women’s college. But I called home regularly, mostly to check on Bridgette and my younger brother, Reggie. When they started referring to dad as “Tommy,” I knew something was up.

I came back to visit Seattle during the winter break of my sophomore year in college. My father greeted me at the door with a smirk on his face and a tight pink turtleneck that hugged his new breasts. I don’t know which made him more proud: having breasts of his own, or so successfully shocking me with them. He was taking hormones.

Soon after that, unbeknownst to me, he started growing high-grade marijuana in the basement. He sold it to finance the sex change. A year and a half into this experiment, two teenagers tried to convince him to let them deal for him. After he refused, they broke into the basement to rob him. When he came down to see what the commotion was, they ran away -- then turned around, stopped, and shot him from 50 feet away.

The police discovered $80,000 of marijuana in my family’s home. The detective assigned to my father’s case speculated that he was three to six months shy of being ready for the official sex-change operation. The detective also said that all the women at the morgue were insanely jealous of my father’s perky breasts. He told me my father’s penis had shrunk to the size of a seahorse.

I don’t know why he shared this. Maybe he could see I was longing to make sense of things. But I was already numb and shell-shocked.

It had been three days since I received the news from my aunt. She called before 9 a.m. “Your father was shot. He died this morning.” And when I heard that word – “died” -- I crumpled to the floor in sobs. That night, I went to a friend’s house and fell asleep after hours of crying, an awful sound that was somewhere between the wail of a child and the howl of a coyote. When I got up the next day, I resolved to silence that wounded animal sound. I was frightened if I gave in to it again, I would lose control completely.

And someone needed to be in control. I needed to book my flight home. I needed to help with the funeral. When I arrived back in Seattle, my mother had not changed her clothes in two days. She’d never been in the best command of her emotions, but this unmoored her. She told and retold the story of how my father died. She tried to take my brother and sister with her to dress my father’s body for the funeral. She thought it would bring closure. But I was mortified, and fought her to leave them home. I couldn’t bear the thought that their last image would be his naked body, ravaged with bullet wounds and the marks of the coroner’s examination. I would have felt this way even if he didn’t have breasts.

She relented, and took a friend to clothe the body on her own. She dressed my father in his favorite pink turtleneck and placed a black doily on his head. One of them applied a garish turquoise blue eye shadow, red lipstick and pink rouge.

The next day, at the bizarre funeral my mother led herself, the director came up to me. “We have never seen anything like this in all our days in business.”

I wanted to laugh, but I was too angry. My father’s death had turned into a complete freak show.

But I got to wave goodbye to the freak show. I returned to college a thousand miles away and shared my experience with my close circle of friends, who were supportive and understanding. Meanwhile, Bridgette went to the middle school down the block from the porch where our father died, staining the cement with a pool of blood. She was teased mercilessly for being the daughter of a cross-dressing, drug-dealing father -- and this was in Seattle, supposedly a progressive place. But kids can be mean anywhere. I wonder sometimes if this is why she began to defend his choices: because she was so tired of being beaten down herself.

My sister grew up with such a different father than I did. He had decided to become a woman by then, and so began to openly shun (and also, I suspect, secretly relish) the stares and disapproval from outsiders. Meanwhile, I had a father who took me fishing and hunting and taught me how to defend myself against an attack.

The irony is that the only person who ever attacked me was my father. When I reached my teens, he set aside the belt and started using his fists. That’s when I left home. I sometimes wonder if he knew that time would come, and wanted to prepare me. I have never known what drove my father’s anger, but it was obvious that he carried around a deep self-loathing. What I don’t know is which part he despised more: the part that wanted to be a woman, or the part that was born a man.

The last time I saw my father was six months before he was killed. Again visiting at winter break. I gave him a small picture of myself and told him that I forgave him. He laughed and said he was sorry. His laughter was often full of mocking. This was one of those times. Each of us offered our words grudgingly. I went back to school thinking, Well, it’s not much, but it’s a start. That was the closest to reconciliation we ever got.

I can forgive him for being abusive, but I confess it is harder for me to make peace with his decision to become a woman. Some of my resistance is based purely on appearance: He never looked like a woman, despite the breasts and makeup. But I suspect there is a deeper reason. If I embrace the idea that he was a woman, it would mean I did not have a dad. I would rather have an asshole for a father than no father at all.

Maybe if he had lived we would have worked this out. We would have had a conversation, I would have learned to live with the contradictions. But instead, there are so many unanswered questions I can’t ask. There are so many things I wish he could help me understand. Therapy has helped me make sense of some of this, but honestly, what pushes me forward most are my dreams.

Years after my father died, I would have a nightmare that he was my enemy, and he was barring me from seeing my brother and sister. This wasn’t so far from the truth. After I left home, he would only let me visit with them if he was present, and he even monitored our phone conversations. But in the dream his actions are harsh, spiteful, unyielding. I would wake up from these dreams with my heart pounding. When I realized he was dead, I felt instant relief that he couldn’t hurt me. Then I felt guilt for being thankful he was gone. I wrestled with that guilt, because I knew he was not the monster this dream was making him out to be. He was very human, very broken, and he saw no other path to happiness. Did it ultimately matter if that path didn’t make sense to me?

I began to feel more compassion toward him, and with that came grief and loss. I have a different recurring dream now. In it my father has faked his death and is alive, happily living as a woman. I am the only one in my family who knows this, and I must decide if I will tell them. I can’t make up my mind. The deep distress I feel over the decision jars me awake. I blink away the dream and find my mind is playing tricks on me again. Then reality hits once more: He is still dead. But I am no longer relieved. Instead, I am surprised to find how much my heart aches to know that he is gone. The simple truth is this: I miss him.

Shares