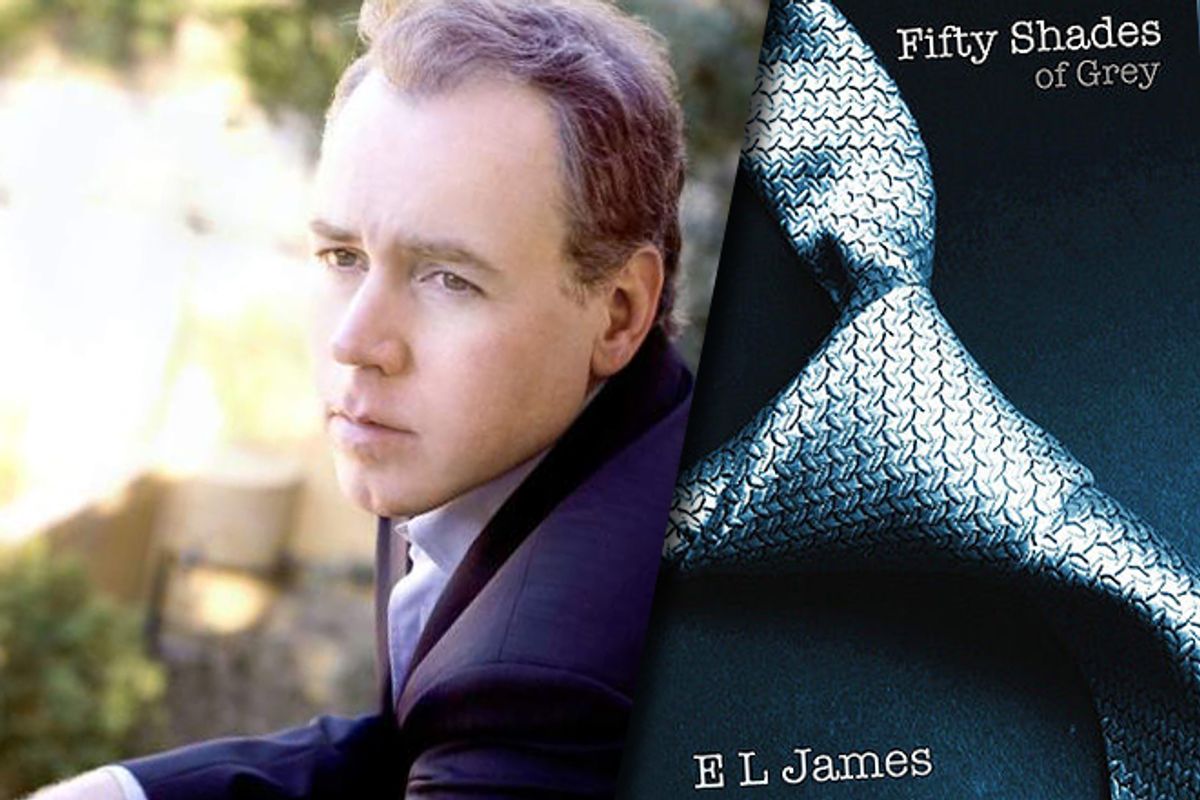

At first, the news that novelist Bret Easton Ellis wanted to adapt the erotic bestseller "Fifty Shades of Grey" for the screen was assumed to be a jest. But no: Ellis confirmed on Twitter last week that he was serious about his desire to write the screenplay: "Completely committed to adapting Fifty Shades of Grey. This is not a joke. Christian Grey and Ana: potentially great cinematic characters."

Ellis has had some reputational ups and downs in the U.S.; many regard him as implicated in the consumerism and celebrity culture he portrays. (British readers and critics seem more respectful.) I haven't liked all his books, but I've liked some. Ellis is, in my opinion, a good writer, one who has interesting ideas. E.L. James, on the other hand, is neither. The notion of the foremost exemplar of "mommy porn" being translated to film by the foremost delineator of late-capitalist decadence struck me as both weirdly apropos and a major waste of talent. And when Ellis tossed out the name of David Cronenberg as a potential director? That was overkill.

Yet it's a truism in Hollywood that bad (or, at least, not especially good) novels make better films than great books do. There's sense in this: A filmmaker may feel more obliged to subordinate his vision to an author's if the book is a patent work of genius, and creative people become less agile when they approach a project on bended knee. Furthermore, what makes a novel great -- the elaborate architecture of the characters' inner lives in "The Portrait of a Lady," say -- is often what's hardest to capture in a dramatic, visual medium, precisely because those are the things that novels do best.

Still, the computer programmers' slang GIGO (for "garbage in, garbage out") remains a reliable rule of thumb: Did anyone really expect the film versions of "The Da Vinci Code" or "Marley & Me" to transcend their source material? The most commonly cited examples of good films made from not-good books are "The Godfather," "Jaws" and "The Bridges of Madison County." Many critics were surprised at the quality of the first "Twilight" film, directed by Catherine Hardwicke. Others point to "Children of Men," which was based on an indifferent science fiction novel by mystery author P.D. James.

It's notable, though, how the same handful of titles comes up over and over again when you ask for examples of bad books that became good films. There are, surely, many more great films based on great books: "Lawrence of Arabia," "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," "The Third Man," the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy and "Rebecca," to name just five. Then there are the books that, despite being faithfully adapted as admired films, never quite measure up to their cinematic versions.

Take "Gone With the Wind." Everything that's wrong with Margaret Mitchell's Old South-worshipping potboiler is also wrong with the 1939 movie: thin characters (except, of course, for the divine Scarlett), soapy plot twists and silly dialogue -- and that's before you get to the historical revisionism and flagrant racism, both manifestations of the novel's pulpy immaturity. But in the movie, this stuff simply doesn't matter as much. The classic Hollywood style, epic visual set pieces and charismatic lead performers sweep such cavils before them.

All a novel has, on the other hand, is words. It can get you inside the characters' heads in a way no film can, and, when done right, it's a better vehicle for ideas. But even a novel as flimsy and agenda-laden as "The Devil Wears Prada" can be boosted to a higher level by the simple introduction of Meryl Streep. Boris Pasternak must persuade you that Lara in "Doctor Zhivago" is beautiful; all David Lean has to do is show you Julie Christie.

Perhaps we're more willing to forgive a film for the faults that damn a book. "The Bourne Identity" by Robert Ludlam is just another formulaic airport thriller, but the Doug Liman film is a respectable exercise in cinematic art. The fact that the content is pretty much the same (action, paranoia) doesn't mean that each work can aspire to the same amount of prestige.

So Ellis could be right, the cardboard billionaire top and his virginal coed bottom from "Fifty Shades of Grey" may indeed be "potentially great cinematic characters." By the time he (and, please God, David Cronenberg) get done with them, they could become the queasily potent reflections of contemporary sex roles and fantasies that their literary counterparts so clearly aren't. James has left Ellis and Cronenberg with plenty of room to work. It's not so much that bad books make better films, as that they don't get in the way.

Further reading

Shares