I argued a few days ago that the constitutional challenge to the Affordable Care Act’s insurance mandate reflects the anarchist-libertarian proclivities of its principal theorist, Randy Barnett. But this invites an obvious objection. The challenge to the mandate is a free-standing argument. It does not expressly rely on its author’s other views. Why think that there is any relation between the two?

One important bit of evidence comes from the questions that three justices saw fit to ask at the oral argument in March. Those questions each presumed that something like Barnett’s philosophical views can be read into the Constitution – and that there is a serious danger that they will decide this case by relying on those views. That is very bad news for anyone who is neither healthy nor rich.

At one point, Solicitor General Donald Verrilli argued that the state legitimately could compel Americans to purchase health insurance, because the country is obligated to pay for the uninsured when they get sick.

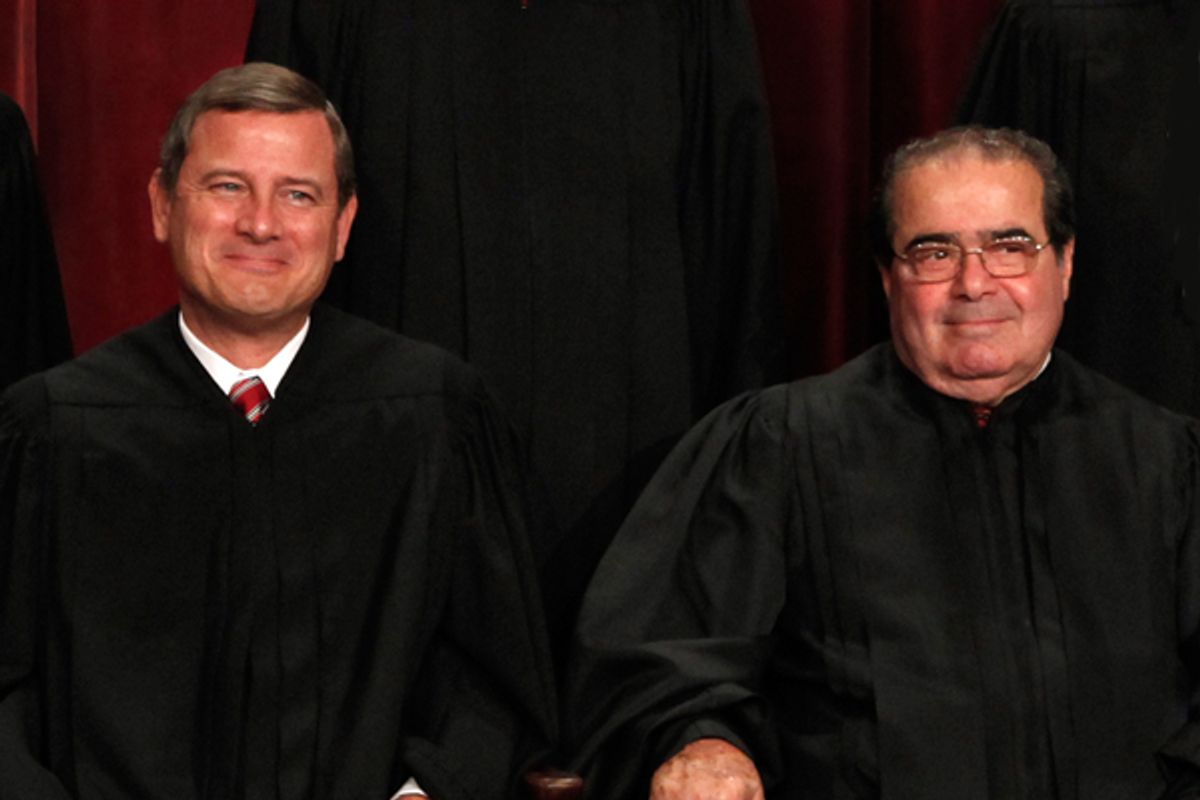

Justice Antonin Scalia responded: “Well, don’t obligate yourself to that.”

One wonders what Verrilli must have thought of this. Scalia was saying, in effect, that there is no real obligation to care for sick people who cannot afford to pay for their own medical care; that any assumed “obligation” is really a discretionary choice. You can choose to obligate yourself or not.

Verrilli merely replied that the Constitution did not “forbid Congress from taking into account this deeply embedded social norm.” Scalia didn’t argue with that, but he still was not satisfied. A bit later, he suggested that under the Constitution, “the people were left to decide whether they want to buy insurance or not.” This would mean that any federally required insurance scheme was unconstitutional. It would trash Medicare and Social Security.

Comments like these at the oral argument stunned many legal analysts and led them to quickly revise their view that the law would easily be upheld. Most prominent was CNN reporter Jeffrey Toobin’s declaration: “This law looks like it’s going to be struck down. I’m telling you, all of the predictions, including mine, that the justices would not have a problem with this law were wrong. I think this law is in grave, grave trouble.”

The legal arguments against the mandate are nonsense. The Constitution’s text and the Court’s earlier decisions provided no basis for finding any constitutional problem with the statute. The objections were badly underdeveloped when Congress passed the bill, and remain deeply flawed. How, then, was it possible for the Court to take these arguments so seriously?

One explanation offered by many is that these judges are pure political partisans, who care only about dealing a defeat to a Democratic president. Another, nicely developed by Ezra Klein, is that a carefully orchestrated campaign made arguments seem plausible that a bit earlier were obviously off the wall, and so gave the Court permission to radically reshape the law. But there is a deeper and even more disturbing explanation. The judges were relying upon a philosophical objection to the law.

The philosophy they relied upon, which I’ll call Tough Luck Libertarianism, holds that property rights are absolute and any redistribution to care for the sick violates those rights. If you’re sick, and you can’t afford to pay for medical care with your own money, that’s your tough luck. The judges’ willingness to read this notion into the Constitution is very big news, dwarfing even the fate of the ACA, which is itself the most important social legislation in decades.

The central purpose of the ACA is to reduce the number of the uninsured. The crux of the case is the act’s so-called individual mandate, which is really a tax that must be paid by individuals who fail to meet a minimum level of health insurance coverage. This mandate is the focus of challenges to the law. A central purpose of the ACA was to extend insurance to people with preexisting medical conditions, whom insurers had become very efficient at keeping off their rolls. But the rule against discriminating against those people, standing alone, would mean that healthy people could wait until they get sick to buy insurance. Because insurance pools rely on cross-subsidization of sick people by healthy participants, that would bankrupt the entire health insurance system.

Massachusetts, acting a few years before the federal law, combined its guarantee of coverage with a mandate, but seven other states tried to protect people with preexisting conditions without mandating coverage for everyone. The results in those states ranged from huge premium increases to the complete collapse of the market. In New York, for example, the individual market dropped from 752,000 covered persons in 1994 to 34,000 in 2009.

Justice Scalia suggested that there was no real difficulty: “You could solve that problem by simply not requiring the insurance company to sell it to somebody who has a condition that is going to require medical treatment, or at least not -- not require them to sell it to him at a rate that he sells it to healthy people.” In other words, you can solve the problem by deciding that it isn’t a problem. Ensuring that everyone has insurance may be something that government is simply not permitted to do.

Why would that be impermissible? Justice Anthony Kennedy explained:

the reason this is concerning is because it requires the individual to do an affirmative act. In the law of torts, our tradition, our law has been that you don't have the duty to rescue someone if that person is in danger. The blind man is walking in front of a car and you do not have a duty to stop him, absent some relation between you. And there is some severe moral criticisms of that rule, but that's generally the rule.

And here the government is saying that the federal government has a duty to tell the individual citizen that it must act, and that is different from what we have in previous cases, and that changes the relationship of the federal government to the individual in a very fundamental way.

Kennedy seems to think that the old common law rule of no duty to rescue – one that, he acknowledges, is morally dubious – could be a matter of fundamental right, such that there is some constitutional impediment to changing it. And this impediment comes into play not only when someone is required to engage in some physical act, but when someone is required to pay money for someone else’s benefit.

Justice Samuel Alito, offering a different objection to the law, thought it “artificial to say that somebody who is doing absolutely nothing about healthcare is financing healthcare services,” and demanded that the United States concede that “what this mandate is really doing is not requiring the people who are subject to it to pay for the services that they are going to consume? It is requiring them to subsidize services that will be received by somebody else.” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg responded: “If you’re going to have insurance, that’s how insurance works.” But Ginsburg’s response was not necessarily devastating.

It depends on what kind of thing healthcare is: Is it a basic right, something that should be available to everyone regardless of their health and wealth, or is it an ordinary commodity? If it is the latter, then Scalia, Kennedy and Alito are right: It is fair to make everyone pay for their own coverage, and insurers should make their customers pay premiums in line with the risks they represent. If you are too poor to buy insurance, that’s tough luck: You can’t get something in a market unless you pay for it. If you have been sick in the past, that’s tough luck, too: Your insurance will be ruinously expensive and the policy won’t cover the illnesses you are most likely to get. This is Tough Luck Libertarianism. Barnett is perhaps its most articulate contemporary proponent.

Markets are normally good for consumers. Providers compete to provide high-quality products. But insurance markets are different.

An insurer profits by taking in a lot of premiums and paying out as little as possible in claims. In health insurance, that means that there is an incentive to restrict one’s pool of customers to young, healthy people and to cancel the policy of anyone who gets really sick. The least expensive 50 percent of health consumers account for only 3 percent of the costs. The most costly 10 percent account for 70 percent of the costs. So competitive pressures move the system toward denying care to those who most need it. Insurers who become skillful at protecting themselves from large payouts by excluding coverage for preexisting conditions, and by raising rates or canceling policies for individuals who become sick, will financially outperform their competitors. They are behaving rationally, in ways that a well-functioning market will reward. (One reason why the for-profit insurance companies were reluctant to support the Obama plan was that risk selection – that is, devising clever ways to keep the sick off their rolls – was what they knew how to do, and under the new law they would not be able to do it anymore.)

The other view we will call the Right to Healthcare. Some members of the community are either too poor to purchase that care, or too sick to be insurable, or both. They will get care only if the responsibility for paying for that care is shared by the society as a whole. That means some system of social insurance, of a kind that exists in every rich democracy in the world except the United States.

If you think there’s a right to healthcare, the American healthcare system before Obama was fundamentally broken. About 15 percent of Americans had no health insurance, and the number was growing. About three-quarters of these people work, more than half of them full-time. Coverage has eroded slightly for employees in the top two-fifths of earners, but more than 90 percent of them remain covered. The middle fifth has gone from 5 percent to 12.4 percent uninsured since 1980. The next-to-bottom fifth have gone from less than 10 percent to 21.9 percent uninsured, and the bottom fifth has gone from 18 percent to 37.4 percent. (These numbers come from Lawrence R. Jacobs and Theda Skocpol’s “Health Care Reform and American Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know.”)

The uninsured suffered avoidable illness, received less preventive care, were diagnosed at a more advanced disease stage and, once diagnosed, received less therapeutic care. Having health insurance would reduce their mortality rates by 10 to 25 percent, according to John Z. Ayanian. For example, women without insurance are nearly 50 percent more likely to die of breast cancer, because their tumors are not diagnosed at an early stage. Lack of health insurance is responsible for between 22,000 and 45,000 deaths every year. Those who don’t die are often financially ruined by medical expenses.

If the Right to Healthcare view is accepted, the money has to come from somewhere. Unlike many other rights, this one can’t be enforced just by making government leave people alone. A person bleeding to death on the sidewalk is being left alone by the government.

One option is to tax citizens directly, as is done with Social Security and Medicare. Another is to mandate that businesses provide the services and collect the cost from their customers; that was once done voluntarily by insurers and hospitals, before costs and competitive pressures made them stop, and it happens now when emergency rooms are required to treat indigent patients (though those hospitals are also quite willing to dun uninsured patients for thousands of dollars). Tax incentives can be provided for the purchase of insurance. Employers can be required to provide insurance (though this is hard on small businesses, and no help to the unemployed). The ACA’s mandate is just another technique for financing broad coverage, adopted, despite its unpopularity, because all the others had proven politically or practically unworkable.

The choice between these two views, commodity and shared responsibility, has for a long time been a political one, and American health policy has been about intermediate possibilities. The ACA moves in the direction of shared responsibility, but there is still plenty of scope for the commodity model: Rich people will continue to get better care than poor ones, and policies will be cheaper for the healthy than for the sick.

What was radical about the suggestions of Scalia, Kennedy and Alito was their implication that the choice between these two models is not appropriately a matter for politics at all, that fundamental fairness is violated by the Right to Healthcare view. Tough Luck Libertarianism may be a constitutional requirement. That suggestion has implications that go far beyond the mandate. If it is unjust to require anyone to subsidize anyone else, then even the graduated income tax (which, inconveniently, the 16th Amendment specifically authorizes) would have to go. If someone is indigent and in need of medical care, that person might perhaps be aided by private charity, but it would be unjust for the state to commandeer taxpayer dollars to aid them, or to require private parties to do so. Scalia’s “don’t obligate yourself to that” is phrased in the imperative. It itself states a moral obligation.

We will find out on Thursday whether these repellent moral imperatives have been read into the Constitution. But the fact that these judges are willing to take them so seriously is already very big news. If Mitt Romney is elected president, and gets to appoint the successors of the aging Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, then we may indeed find ourselves in a world where Tough Luck Libertarianism is imposed on us from the bench.

Shares