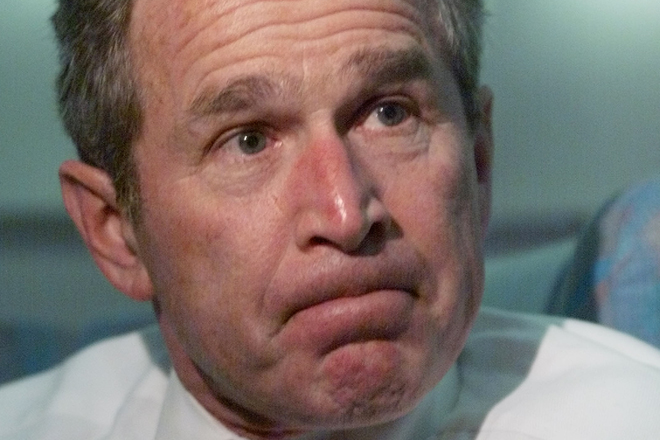

In 2003, President Bush, then two years into his tenure, was asked by journalist Bob Woodward about his place in history. “History,” he replied. “We don’t know. We’ll all be dead.” This is a remarkable statement from any president, suggesting a blithe attitude toward the job’s magnitude and responsibility to posterity. Compare this insouciance, as historian Sean Wilentz did in a searing Rolling Stone piece on the younger Bush, with another president’s observation on the subject. “Fellow citizens,” said Lincoln, “we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation.”

Wilentz’s Rolling Stone piece, appearing in the spring of 2006, with Bush still in office, posed a question: Was this president the worst ever? The Bush presidency, wrote Wilentz, appeared “headed for colossal historical disgrace,” and there didn’t seem to be anything Bush could do to forestall that fate. He added, “And that may be the best-case scenario. Many historians are now wondering whether Bush, in fact, will be remembered as the very worst president in all of American history.”

In the 5,500-word analysis that followed, Wilentz presented a solid case, although some of his arguments and expressions sounded more like they emanated from the Democratic side of the U.S. House floor than from a dispassionate historical examination. Like his good friend Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Wilentz has nurtured a career combining rigorous scholarly pursuits with occasional vectors of partisan advocacy for Democratic causes. But the question deserves attention, and Wilentz poses it with verve and pungency.

Bush began his presidency with a burden — his 2000 victory emerged in the country’s most hotly contested election since 1876, with the final outcome determined by a 5-to-4 Supreme Court decision. This naturally generated some lingering political animosity in the country. It can be argued that in the early months of his administration Bush worked effectively to establish the legitimacy of his presidency. But even early on it sometimes seemed that Bush confronted weighty presidential decisions with the same blithe attitude that characterized his answer about history’s judgment. He often appeared to have his eye fixed more on immediate outcomes than on long-term consequence. In taking his country to war in Iraq, he failed to meet the two fundamental tests of presidential war-making. One was the Polk lesson: Ensure that no one can ever make an accusation that the president dissembled with the American people in order to get permission to spill American blood. The other was the Lyndon Johnson or Harry Truman lesson: Ensure that the country doesn’t get bogged down in a war it can’t win and can’t end. Avoiding these ominous pitfalls would have required a sober and solemn assessment of all the risks and dangers of the enterprise, both military and political. There is little evidence that Bush conducted such an assessment before his war decision.

In building an intellectual foundation for his war, Bush crafted a rationale of necessity and a rationale of success. The former encompassed the reason why America needed to invade Iraq, and that reason was twofold and interconnected: weapons of mass destruction and the Iraqi government’s flirtation with Islamic terrorists. The two together, according to the Bush reasoning, constituted a major national and global threat that required immediate action. It turned out, however, that the weapons of mass destruction didn’t exist, and the connection with terrorists couldn’t be established. Hence, the rationale of necessity collapsed after the invasion, and Bush was diminished in much of public opinion for having crafted a rationale for war that was either disingenuous or carelessly flimsy (I believe the latter).

The rationale of success is more complex. When presidents take the country to war, they must present a depiction of victory — how U.S. forces will meet the military challenge, how they will subdue the enemy, how they will maintain control over the situation throughout hostilities and afterward, how the president will avoid the kind of geopolitical trap that ensnared Truman in Korea and Lyndon Johnson in Vietnam. To fashion his rationale of success, Bush reached back to the gauzy notions of Woodrow Wilson. As Wilson had sought to make the world safe for democracy, Bush would make Iraq hospitable to Western democratic institutions, and the resulting stability would ensure the success of the military enterprise — and serve as regional example and beachhead for similar Wilsonian initiatives throughout the Middle East.

This was — there is no kinder word for it — delusional. It rested on the idea that America could foster world peace by spreading throughout the world its democratic ideals, viewed widely in the West as universal. But they aren’t universal. Particularly in the Middle East, many people consider American values to be an assault on their own cherished cultural sensibilities. And America’s political and economic models are losing force in the consciousness of other peoples around the world. China, for example, competes with America not just economically and increasingly in the military sphere, but also in its view of the best approach to government. The China model is stirring interest and enthusiasm around the globe. As Stefan Halper of the University of Cambridge in England writes, “Given a choice between market democracy and its freedoms and market authoritarianism and its high growth, stability, improved living standards, and limits on expression — a majority in the developing world and in many middle-sized, non-Western powers prefer the authoritarian model.”

Hence the Bush war policy was based upon an idle fancy, and the war’s outcome bore little resemblance to what was advertised. There was no widespread welcoming of American military “liberators,” as administration officials had predicted. There was no blossoming of peaceful democratic practices. There was no beachhead for further Wilsonian pursuits in the region. Instead, the American incursion detonated a wave of sectarian killing — and growing casualty rates for Americans as the U.S. military found itself trying to subdue the violence. The later Bush “surge” of additional troops didn’t constitute a military success, as is sometimes argued, but rather amounted to a negotiated peace with the country’s minority Sunnis, who had been devastated by the majority Shiite factions and needed American protection.

U.S. casualty rates declined thereafter, however, which helped diminish domestic opposition to the war. Still, the president’s standing took a hit based on the collapse of both the rationale of necessity and the rationale of success, the chaos unleashed in Iraq by the American invasion, the strains placed on the American military, and the lingering military presence there without a clear sense of a worthy outcome.

Remember, though, that the American people judge their presidents largely in four-year increments, and by the time Bush faced the voters for reelection in 2004, not all of these negative factors had come fully into focus. What’s more, the national economy was percolating nicely. Hence, there was no particular reason to turn Bush out of office, although the electorate wasn’t about to give him much of a mandate. He collected only 51 percent of the popular vote and took the Electoral College contest by a mere 35 ballots.

On the economy, many Bush critics like to point out that real GDP growth averaged only about 2.1 percent a year during his eight years. True. But that misses the significance of referendum politics in presidential elections. Bush took office with a mild Clinton recession in progress, and hence his 2001 GDP growth rate was dismal (though he wasn’t blameworthy) — just over 1 percent (which brings down his average percentage). But the economy picked up nicely in the next three years, with GDP expanding by a respectable 3.47 percent in the reelection year. That certainly helped propel him to his November triumph. We have since seen a hearty partisan debate over the impact of Bush’s early tax-cut initiatives in helping to foster this growth. Democrats, including Wilentz in his Rolling Stone article, argue vehemently that there was no connection, while Republicans have insisted the link is clear. My own view is that, with the waning of the powerful productivity wave that helped fuel Clinton’s growth performance, a tax stimulus was probably needed. But we needn’t adjudicate that argument here because, in any event, the president always gets credit or blame for what happens on his watch. And Bush’s first-term economic performance merited the appreciation it got from the voters.

It was during the second term that things fell apart. The folly of the Iraq war became increasingly clear, and Bush’s credibility plummeted. The war sapped federal resources and threw the nation’s budget into deficit. The president made no effort to inject any fiscal austerity into governmental operations, eschewing his primary weapon of budgetary discipline, the veto pen. His first budget director, Mitch Daniels (later Indiana governor), strongly urged a transfer of federal resources from domestic programs to the so-called War on Terror, much as Franklin Roosevelt directed such a transfer when he led the country into World War II. Bush rejected that counsel and allowed federal spending to flip out of control. The national debt, which was being steadily paid down under Clinton, shot back to ominous proportions. Meanwhile, economic growth rates began a steady decline, culminating in a negative growth rate in the 2008 campaign year.

Contributing to Bush’s problems was a personality trait that hindered his ability to work with others in the political arena, particularly the opposition Democrats. He brought to his presidency a high level of sanctimony — an apparent conviction that he operated on a higher plane of rectitude than other politicians. Sanctimony, as noted earlier, is not a trait that contributes to smooth effectiveness in the political game, and sanctimonious presidents — Quincy Adams, Polk, Wilson, Carter and the second Bush — almost inevitably have found themselves isolated and beleaguered. All brought upon themselves unnecessary difficulties traceable to their self-righteous temperaments.

In Bush’s case it was seen in his refusal to acknowledge any major mistakes, which made it difficult for him to change course when inevitable setbacks demanded flexibility. This rigidity not only kept him clinging to failed policies but also created the spectacle of the president issuing what conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr. called “high-flown pronouncements” about plans and programs seen widely by others as hopeless. Worse, Bush’s tendency toward sanctimony militated against the kind of compromises needed to lubricate the gears of government. Listening to naysayers helps politicians understand the forces swirling through the nation, but Bush demonstrated little interest in doing so. He tuned out the naysayers, whether from the other party or his own inner circle. “No other president,” writes Wilentz, “. . . faced with such a monumental set of military and political circumstances failed to embrace the opposing political party to help wage a truly national struggle.”

It wasn’t surprising, based on all this, that Bush’s standing with the American people plummeted through his second term, that his approval rating in the Gallup Poll would drop to the lowest level of that of any president in thirty-five years, and that his party would be expelled from the White House at the next election. The key was the independent vote, which Bush split with his Democratic opponent, John Kerry of Massachusetts, in 2004, but which turned away from the Republicans four years later.

Does this mean Wilentz is correct, and history will relegate Bush to the very bottom of the presidential heap, lower even than Harding and Buchanan? Impossible to know. But, based on the contemporaneous voter assessments, the objective record, and what we know of history, it’s difficult to see him even in middle-ground territory. History likely will view Bush largely as the voters did after eight years of his stewardship. And so it’s probably just as well that he doesn’t care much about the verdict of history.

From WHERE THEY STAND by Robert W. Merry. Copyright © 2012 by Robert W. Merry. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster.