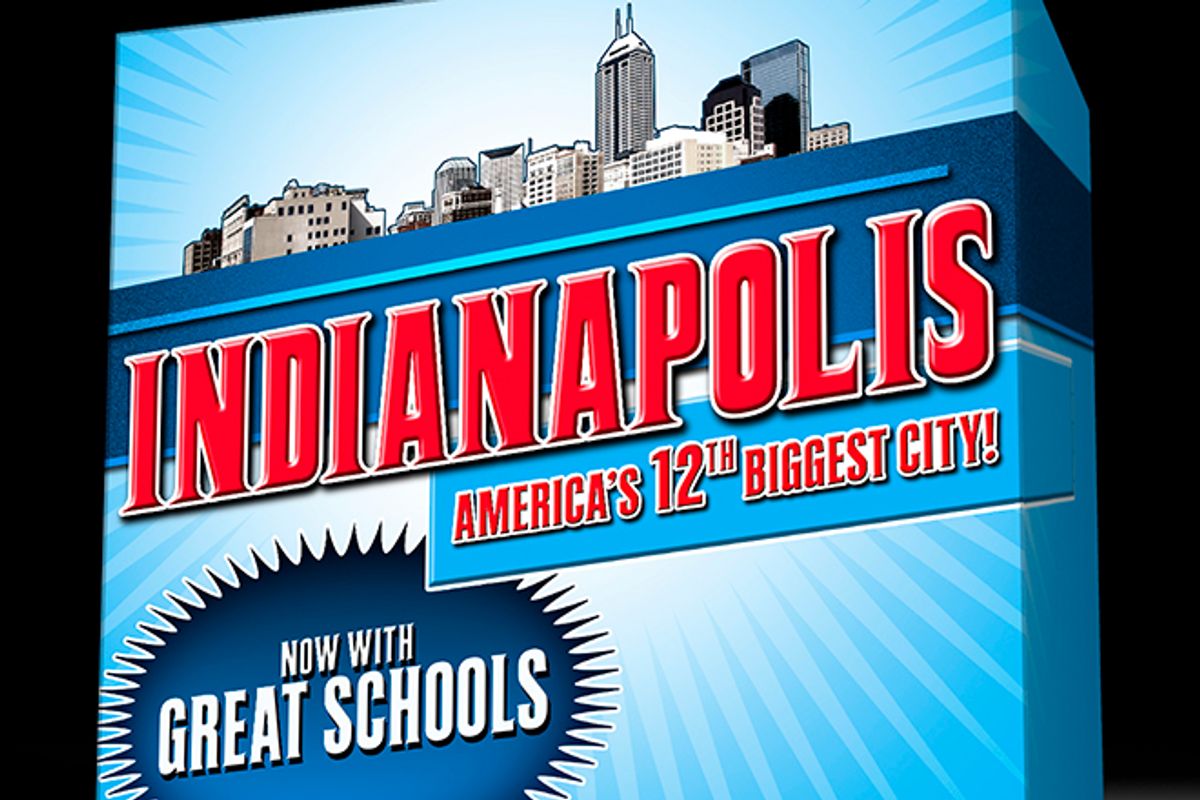

When you think of Indianapolis, what springs to mind? Besides the annual Indianapolis 500 race. Take a minute to sum up the essence, the unique identity, of the Midwest's second-largest city.

It's hard to do -- not because Indianapolis doesn't have a unique identity, but because if you don't live in or around it, you probably have no idea what it is. There are lots of cities like this. For every clearly defined Detroit, New Orleans or Las Vegas, there's a more amorphous Columbus, Ohio; Louisville, Ky.; or Providence, R.I. "People move to Indianapolis because it's cheap, has great schools, is family oriented and offers easy living," says urban analyst Aaron Renn. "Those are hard things to brand. For outsiders, it can be difficult to understand what it's all about."

A few years ago, unless you were a tourist mecca, this didn't matter so much. Some places had big personalities (Dallas has always been DALLAS!), but many cities didn't bend over backwards to market an identity. Then along came the knowledge economy, the work-from-anywhere jobs and the renewed fascination with urban life. Suddenly cities that never felt they needed more PR than a catchy nickname began mapping out multi-tiered branding strategies, taking a fresh look at their image and even trying to create a whole new persona that they hoped would be a better sell.

But futzing with a city's identity is tricky business, as Renn illustrated last week in an article about the downward slide of Chicago. A decade or so ago, Chicago's leaders decided they no longer wanted to be anything as stodgy as "the capital of the Midwest," he writes. Instead, they would be a global city like New York, London or Hong Kong. Gobs of money were poured into big-ticket starchitecture, a high-design park and an Olympic bid. It didn't work -- by a variety of metrics, from population to GDP, the city is losing ground.

Renn cites a constellation of reasons, but perhaps the simplest is that Chicago ran away from its own DNA as the City of Big Shoulders. "It's always been a rough-and-tumble, wearing-your-shoe-leather-out kind of place," he says. "Now you see it sponsoring fashion initiatives. Nothing wrong with that, but if you make fashion the base of where you stake your claim in the market, you're going to lose." (Of course, a soaring murder rate and a stalled economy probably have something to do with it, too.)

Chicago's mistake was chasing a standardized formula for success, says Renn. "There's this tremendous fear of doing anything that's out of the ordinary. Whenever some fad gets hot, whether that be 'creative class' or streetcars or bicycles, everyone jumps on it. Every city says they want to be the No. 1 bicycle city in America -- whether or not that would actually work for them. They're all trying to check the boxes of what they think makes a world-class city instead of thinking of how they can add some new boxes."

In 2006, a 26-page report put out by a group called CEOs for Cities and a brand consultancy called Prophet detailed a strategy to transform the Windy City's "current brand image" of Capone-era gangsters and epic blizzards into a more sophisticated "aspirational brand identity." (Prophet did not return a request for comment.) "The ultimate goal is to understand how the target audience perceives the place today so that the gap between the current state and the desired or aspirational state can be assessed," it read.

But too thoroughly scrubbing a city of its "current brand image" can leech a city of the quirks that make it stand out. "Keep the heritage of the brand intact" is Rule No. 1 in marketing. "Chicago has done its best to suppress this notion of the gangster city, but you go overseas and say you're from Chicago, and people are like, 'Oh, Chicago! Bang, bang!'" says Renn. "It's obliterated its gangster icons."

Compare that with Nashville, a city with steady population growth and lower-than-average unemployment that has held fast to its roots as a country/Christian music destination. "Nashville has done an amazing job at rebranding without losing its identity. They're still all about country music, but it's not just the Grand Ole Opry. They've glitzed it up into something new -- they call it NashVegas. It's a glitzier version of what it used to be."

The notion of coordinated, centralized city branding was invented several decades ago in New York, according to Miriam Greenberg, author of Branding New York: How a City in Crisis Was Sold to the World. New York's troubles in the 1970s were severe even for the time. Getting off a Greyhound at the Port Authority Bus Terminal, a visitor might find a brochure pressed into their hand with a picture of a death's head and the words, "Welcome to Fear City." The brochures, which warned people to stay off the subway and to avoid going out after dark, were a protest by city workers angry about fiscal austerity measures.

In response to this and other assaults on the city's image (the exploitation films, the sensational coverage of the '77 blackout and "Summer of Sam"), city hall, in cooperation with local business interests, led an attempt to seize control of New York's identity with a highly orchestrated, carefully plotted image makeover. "There were boosterism efforts that preceded this period," says Greenberg, "but the idea of a city like New York or San Francisco or Atlanta, with a diverse economy, suddenly involving itself in that level of marketing was a new phenomenon."

Ten billion "I HEART NY" shopping bags later, the city's branding push continues, and in fact has become more professionalized than ever under the Bloomberg administration. "There's been a restructuring in terms of economic development in the city under Bloomberg, making New York a commodity to be purchased and invested in by elites and corporations around the world," says Greenberg. "There's this idea that you have to burnish the city as a product, like Nike branding the Nike lifestyle. They're targeting very specific tourists, corporations and investors." Bloomberg's foot soldiers maintain 18 international offices where, in the city's own words, "the team manages the New York City message to consumer and trade media as well as key stakeholders and government officials." Even the official NYC logo that's now used by every city agency is meant to "map the city's identity onto all operations, similar to how the private sector talks about 'brand architecture,'" says Greenberg.

In New York's case, the efforts have become mainly about refining the city's familiar brand. But what about a city like Indianapolis, with an identity that's less recognizable to outsiders?

You could say that Indianapolis's big branding debut occurred on February 5, when the city hosted its first Super Bowl. It was a PR bonanza -- Forbes declared the event's true winner to be Indianapolis, even though the New York Giants won the game. Several major networks announced that it was the best Super Bowl experience they'd ever had: "I have never seen a city that seems to have more of their business in order," summed up ESPN. Visiting reporters gushed about the "Hoosier Hospitality" -- "It's like everybody's on Xanax," observed Sports Illustrated -- but they also, surprising some viewers, talked up the restaurants and cultural offerings. "There's been a methodical march to grow tourism here over the last decade," says Chris Gahl, vice president for marketing and communications for the Indianapolis Convention and Visitors Association (ICVA). Super Bowl XLVI was a moment for which the city had been rehearsing for years.

That moment didn't arrive by luck -- the slow and steady effort to establish Indy as the sports capital of America began over a decade ago. In 1999 it lured the NCAA away from Kansas City, where it had been headquartered since 1952. In 2003, the city hashed out an unprecedented deal to host basketball's Final Four at least every five years until 2039. And in 2008 it opened Lucas Oil stadium, where this year's Super Bowl, which was watched by more people than any event in American television history, was played. Along the way, the city doubled the size of its convention center, opened the world's largest JW Marriott hotel, and built a new $1.1 billion airline terminal. The goal was to show that since the city can deftly handle large sporting events, it's a natural fit for big events of all sorts, from conventions to big-ticket concerts.

For 20 days before the big game and 20 days after it, 46 volunteer bloggers who were selected by Klout score each promoted a different facet of the city: Nightlife, transportation, restaurants, etc. This was an expansion of a year-round effort -- ICVA employs a full-time social media strategist, puts out a weekly video podcast, and pays bloggers to grow promotional content online. It also hosts about one hundred reporters a year.

The branding strategy, says Gahl, has always been to build on the city's sports cred as a base -- including its famous car race, whether it's seen as declasse by the "global elite" or not. "Indianapolis's brand has always been connected to the Indy 500," says Gahl. "You can offer up new exhibits and museums and hotels, but just as important is letting your brand develop organically and authentically. Every destination fights stereotypes. We don't hide behind the fact that we're a sports-minded city. Where we're concentrating our efforts now is changing the vanilla image to a more distinguishable image outside of sports that showcases the city."

Football, car racing, competence, all-American, warm and friendly, fun downtown -- it's a jumble of attributes and imagery that any marketer would kill for. The trick is crystalizing it into something that makes people think, Indianapolis is where ________ happens. The city has worked very hard recently to fill in that blank.

"What leaders can do is spend some time thinking about what the Gestalt of all their good attributes are," says Renn, who's lived in Indianapolis and thinks the city has plenty of brand potential. "No one's going to believe that Indianapolis is super-fashion-forward, and that's fine. What are the unique values, history and culture that make up your brand? Because you have one, whether you know it or not. Every city's got a story to tell."

Shares