Your book Sex and Punishment: 4000 Years of Judging Desire is a fascinating read. On the cover Mary Beard describes it as “an exposure of attempts to regulate sexual activity.” Do you think that sexual activity can ever be regulated?

I was thrilled to get that quote – it was almost like a validation. But no, as my book shows, the regulation of sexual activity is always a work in progress. It’s a series of give-and-take measures governed by a lot of moving parts – the morals of the time, the political needs of whomever is in power, the social needs of those being regulated and, more than anything, the tolerance of the population for the level of punishment being handed out. Often the absence of regulation is as interesting as regulation. I looked for where the law doesn’t exist as much as for where it does.

Something else I found, reading your book, was the way that the reasons for regulating sexual behaviour changed. At the start it was more a question of property and ownership, and it’s only perhaps with the advent of Christianity that it becomes about moral factors.

Christianity, and particularly Judaism. The attachment of moral right or wrong to individual sexual activities is really a Biblical thing. That wasn’t made up out of whole cloth – I think people used sexual morals to define themselves, and to define themselves vis-à-vis other cultures. When God came down in a theoretical bolt of thunder and instructed Hebrews how to behave themselves, he specifically said “don’t do as they do in the surrounding areas” – areas they were about to ethnically cleanse – “but define yourselves differently. And if you don’t do what I command you to do, to avoid homosexuality et cetera, then I will vomit you out of the land.” So starting with the Bible, an individual sexual transgression became an act of sedition against the whole society. That was picked up by the Christians – the new notion that one person’s sin put everyone else at risk, which raised the stakes enormously.

It’s a little like the feminist Carol Hanisch’s phrase, “The personal is political.”

Absolutely. The personal is political, and the personal is also incendiary. Part of the reason for sexual laws was to define one culture as distinct, different and very often better or worse than another. So in a pagan society – not in a pejorative sense, but meaning a non-Jewish or non-Christian society – it was a question of channeling and managing the sexual urge in order to prevent trouble in society, or it was to do with the passage of property from one generation to another. With the advent of Judaism and Christianity, sex became a group concern, and there was very little difference between body and spirit.

You cover a very broad period, from ancient Mesopotamia to the end of the 19th century – your reason being that otherwise the present would dwarf the past. But there are references throughout to modern thinking. Often you read about what people thought in the Middle Ages, and then find a US senator in the late 20th century held the same views.

If I had continued, the last chapter would have been at least 450 pages long. I’m working on volume two of the book, and I’m deliberately feeding this one with contemporary issues. But you can’t help but make associations, and it’s valid to do so.

Where do you think Western civilization is now, on a scale of liberal to conservative, in terms of sexual regulation?

I think it would be too easy to say not as far as we think. The truth is that we have actually come quite far. In particular, we have come far when it comes to freedom of sexual activity without risk of undue punishment, such as the decriminalization of adultery and homosexuality, at least in the US and the UK. I think we’ve come a long way in agreeing that one person’s homosexual life has no appreciable effect whatsoever on the lives of others. It’s still a volatile subject which comes up in a hundred different ways, and the rights won are very easily lost. But I think all societies move forward and backward at the same time.

At the same time, we’ve also increased the criminalization of other acts, such as sex with younger people and children, which no one would have ever tolerated. I pay a lot of attention to that in my book, especially in the last chapter, because it’s significant. We now have laws which make it a very serious crime to take advantage of someone of a certain age. That age changes from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Sex with a 14-year-old in Germany isn’t any less immoral than sex with a 14-year-old in England [but it is a crime in one country and not in the other]. Across the Western world, we now have a sense that it is wrong to use power, influence, age or authority to extract sex from someone who doesn’t have those attributes.

We’ve also come far in that there’s an industry of sexual harassment in the workplace, meaning that a woman – it’s usually women – of a lower class or economic position can now seek to redress the balance in court against men who use their class or economic position, for example as an employer, to intimidate or extract sex from them. That’s an increased criminality of sexual activity, but it also shows the evolution of morality. Roman Polanski is the easiest case to refer to. He had sex with a 13-year-old girl in Los Angeles, but if he had been caught in California a century before, he would have been well in the clear. No problem. The notion of an older man taking advantage of a younger girl or woman was until recent times – in your lifetime and mine – considered a birthright.

Moving onto the books you’ve picked out for us, let’s start with The Picture of Dorian Gray. Oscar Wilde’s trial is also the point where you chose to end your own book.

The Picture of Dorian Gray is now a part of the canon that no one would admit to not having read. Most of us have read it and delighted in its witticisms. It’s hard to imagine, but when Dorian Gray was first published, the book was not well received at all. It was totally panned. It was held against him as being an example of an effete character. It was being serialised by Lippincott’s Magazine, and the serialisation of the novel stopped when it became too inflammatory.

One of the reasons why I wanted to recommend this book is that it is an example of literature being used as evidence itself. Most of us know the bones of the situation of Oscar Wilde being put on trial in 1895 – the father of his [homosexual] lover became inflamed and found all kinds of characters to use against him [in court]. During his trial, Oscar Wilde had to answer for the attitudes expressed by the characters in The Picture of Dorian Gray.

We need to stop and think about that. There was a brilliant cross-examination rendered against him. In court, the lawyer who took him on was remarkably talented. He essentially said to Oscar Wilde: “Do you hold these views? Is this your belief?” Oscar Wilde was quite brilliant, but not brilliant enough to see what was being done to him. He very aggressively adopted the views, thereby admitting his proclivities and then having to answer for the fact that in England, at that time, private sexual activity between men was punishable by two years of hard labour.

The key point about Dorian Gray is whether a writer must answer for the thoughts and ideas of the characters that he writes. And in this case, he did. It worked very much against him. I wonder whether writers today – who write about murder, perversion and all of the terrible things that populate books and television – should ever be called to task for the thoughts and ideas expressed in their work. Most of us would say that should never happen. There’s a very large difference between the composer and that which is composed.

You mention other trials in your book – Flaubert for Madame Bovary and Baudelaire for Les Fleurs du Mal, for instance. Both are covered in your second choice, Disorder in the Court.

I highly recommend Disorder in the Court. It’s a wonderful collection of essays, each covering major trials involving sexual misconduct in the second half of the 19th century. They each isolate a specific trial, always ones that were very well covered, and use the legal proceedings to provide insight into how we think about ourselves.

One of the essays deals with the trials against Flaubert and Baudelaire, both in 1857. What’s remarkable about these trials is that censorship was dependent on the market. In 1857, novels were not considered terribly serious works of literature. When Flaubert wrote Madame Bovary, it was presumed that the audience was female, and that this female audience had more delicate and impressionable sensibilities. So because the book dealt with an adulteress, and there was no character in the book formally condemning adultery, Flaubert was called to task for not writing a morally uplifting book. The idea was that women who read novels should be coddled and uplifted by them. Fortunately for Flaubert, this made his career. The brouhaha over the trial brought him a lot of notoriety. He escaped full censorship and punishment, but he got a very stern warning.

By contrast, poetry was considered a much more serious business. When Baudelaire published Les Fleurs du Mal, it was a harder job for the prosecutor because the audience was presumed to be men, who were thought to be made of harder stuff. They would be less swayed and influenced by the literature, even though the poems were much more profane. In fact, there were several poems from that collection which were censored for quite some time.

Disorder in the Court follows some other interesting French cases, and also a wonderful case in India involving a young Hindu woman called Rukhmabai. She had been married off at a young age to a man in Mumbai, and had refused to go to her husband. Imagine the courage – she said no. He sued her, he lost. He sued her again, he won. The case became a cause célèbre in London. Fascinatingly, the lower age of consent – which was 10 in India at that point – was taken on by Indian nationalists as an aspect of their national spirit. England was seen to be overbearing, raising the age, interfering with their national affairs.

Rukhmabai ended up coming to England and becoming one of the first female doctors. She was a very savvy media player and wrote a lot of letters to the London Times. It created a huge national debate over Indian sovereignty, and whether the age of consent for dark-skinned women should be different than for English women. Even the consensus of reformers then was that white English women were somehow more delicate and less sexually precocious than women from India, and therefore their age of consent should be higher.

That goes back to what you were saying earlier, about differentiating societies by differentiating attitudes to sexual behavior. Which takes us very nicely to The Children’s Hour. You mention in your book that The Children’s Hour was based on a real case.

It’s a case that I was fascinated by, and one that shows how male attitudes about their own sexuality affects their judgement of female sexuality. This was a case in which two very proper Scottish schoolteachers – two women who ran a private school for girls – were accused of lesbianism by one of the girl’s grandmothers. A girl who heard them in bed told her grandmother, who told other parents, and immediately the two women were ruined. All the parents took their kids out of school, and the women sued the grandmother for defamation.

The trial transcripts are absolutely remarkable. Essentially, the women won because the judges could not accept that two proper, hard-working middle-class women could love each other sexually without the intercession of some male element. The main judge, Lord Benedict, said: “If I distrust these women, if I think that anything more than licentious buffoonery could result from them sleeping together, I would happily distrust my own wife.” We laugh, but this is a serious business. By bringing the case, the women were denying that they were engaged in a sexual relationship, but it’s evident that they were.

Lillian Hellman picked up on this case and wrote it up as The Children’s Hour, which became a very successful Broadway play, although it was banned in London, Chicago and several other cities. But she diluted the plot in very important ways. For one, she set it in a private school in New England – which is no big deal. But in The Children’s Hour, one of the accused women is clearly not lesbian while the other one confesses ultimately that she is, and tragedy ensues. They also lose the case. So the women suffered for their sexuality. The whiff of lesbianism is all over the play, and that’s what really drove it – it was a forbidden subject. But even in the 20th century, with Lillian Hellman writing it, the real truth of the case could not be brought out in a way that accepted that two women could have a healthy lesbian relationship.

Then there was the Hollywood adaptation, which bowdlerised it even further.

I haven’t seen the film but from what I understand it dilutes it even further and takes the question of female homosexuality completely out of the picture.

There was a revival of it here last year in London, with Keira Knightley and Elisabeth Moss.

Yes, and that was the first production of it in London in a very long time. When you see that play in perspective, it becomes much more interesting.

Your next choice, Roman Sexualities, is the second collection of essays you chose.

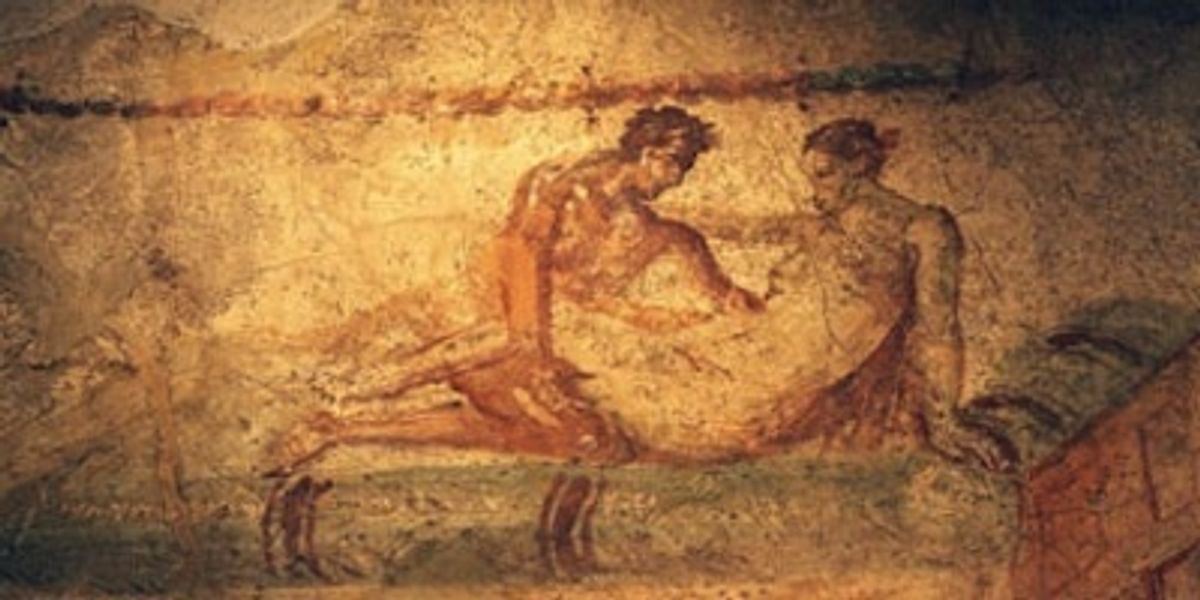

This is more in the academic realm. It’s a collection of essays, published by Princeton, which I found to be very illuminating. It examines Roman sexual attitudes in a very precise way, and it lays out for the reader attitudes that we would find fairly remarkable. For one, it lays out very clearly how futile it is to impose our current notions of hetero, homo or bisexuality on the ancient world – it’s simply not how they looked at it. The notion of sexual contact was not heterosexual or homosexual, as such. There were very few men, if any, who were interested only in women. Emperor Claudius is the only one we can say this about for sure.

The idea of intercourse in Roman times was that it was as a male or as a female. So two men could be making love – or rather, having sex – and for the male in the “active” position, that was perfectly male. It didn’t make him homosexual or shameful in the least. By contrast, being in the “receptive” position, per se, made you female, and it couldn’t have been more humiliating. The notion is of sex as conquest – sex and violence are so linked that one is almost the other.

One interesting point is that the Roman word for “male” wasn’t so much about one’s genitalia.

Yes, the word vir was less about one’s physical make-up than about how one conducted oneself. Also, on the notion of being “taken” by another person, we can’t see sex laws as being in isolation. The person who was submissive sexually was in the same boat as actors or gladiators. Those who used their bodies, whose bodies were either looked at or used for the pleasure of others, and were put into a prone position to be enjoyed by others – that was infamia. It was exactly what you didn’t want. But to have a body that was inviolate, to have a spirit that was inviolate, to be safe from violence or penetration – that is what made a Roman man what a Roman man was.

If a Roman wife had an affair with another man, a very common option for revenge was for the aggrieved husband to rape the other man. That violence was the act of revenge, and more important, it left that man with his reputation shattered. Rape, at least in that context, was anything but sexual.

Your last selection, To Kill a Mockingbird, also deals with themes of rape and violent retribution.

This is another standard that everybody read when they were 14. What I think it really shows is the myth, at least in white America, of the black man as sexual predator – which still exists. The defendant in the case, Tom Robinson, is essentially a cripple. The case, which we tend to forget, was about the rape of a poor white woman. It turns out she was probably raped by her own father. Most rape cases in the United States, for a very long period of time, were against black men. Something like 8 out of 10 of those cases ended up in convictions. Quite often, castration was the punishment.

In this case it’s critical to bring up the notion that permeated To Kill a Mockingbird of any black man being a potential sexual predator. As one court put it, any sexual encounter between a white woman and a black man had to be rape, because “no black man could assume that a white woman would consent to his lustful embraces.” We’ve come a long way from that, but I think that is really at the bottom of the case. Let’s not forget that for most of American history there was no such thing as rape of a black woman – especially black women who were owned by their masters. Part of the benefits of slave ownership was to take sexual advantage of your slaves. There was clearly a double standard.

So the case is about racism, but it’s also about white sexual fear of the black man, and the failed effort of white America to stop intermixing. I think the notion of the scary black man still permeates the American justice system today. Some people are rethinking this book, saying it’s a racist novel, it’s patronizing, et cetera. I don’t think To Kill a Mockingbird is one of the greatest pieces of literature ever. I think it’s been overrated over the years. But it is a very good window into the ingrained sexual fear that permeated at least the Southern American justice system.

Shares