The proposed changes in the diagnostic criteria for addiction in the long-awaited DSM-5, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, scheduled to be published next May, have proved unsettling to many in the treatment community. These largely professional disagreements assumed the status of a public controversy when a May 11 New York Timesarticle reported that Dr. Howard Moss of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism had resigned from the DSM-5 Task Force.

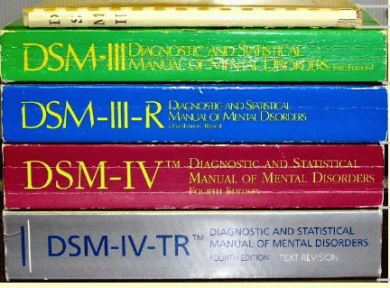

The controversy is hardly surprising. In many ways, writing a new DSMis a sisyphean task. Since psychiatric disorders don’t announce themselves with biological diagnostic data, the coherent organization of a huge number of complex disorders into a “manual” to be used by researchers, healthcare professionals and third-party payers is daunting. How do you capture, in a few pages, illnesses and patterns of suffering that manifest uniquely in every new patient? Consider also that many patients have more than one psychiatric illness and that diagnosis depends, to a certain extent, upon the patient’s own ability to articulate their inner experience. No revision to the DSM would be greeted with universal praise from a field increasingly polarized between viewing nature or nurture as the essential cause.

Addiction professionals need to know that there are likely to be three main changes to the definition of addiction:

1. Adding “craving or a strong desire to use” as a criterion.

2. Replacing the separate categories of substance “abuse” and “dependence” with a unified “Substance Use Disorder” rated for severity (Alcohol Use Disorder, say, or Severe Cocaine Use Disorder).

3. Adding Gambling Disorder to the Addictive Disorders, where previously Pathological Gambling was listed as an Impulse Control Disorder. (This change likely paves the way for other Addictive Disorders in future editions, such as sex addiction and internet addiction.)

What has sparked this heated debate is the expectation that the new definition will result in a great expansion in the number of addiction diagnoses. This alarms some in the treatment community who fear that it will lead to “false epidemics” of substance abuse and “the medicalization of everyday behavior,” inflated statistics about disease prevalence and millions of dollars wasted on unnecessary treatment. To take only one example, with the addition of “craving or strong desire or urge to use [a substance],” a college student who often drinks more than he or she intended to could receive a diagnosis of Mild Alcohol Use Disorder, despite the absence of any serious negative impact—as is currently reflected in the manual.

Along with the fear of unnecessary diagnoses comes the fear of unnecessary pharmacologic treatments. Critics argue that the changes in the diagnostic criteria and the availability of psychotropic medications for cravings may lead to an increase in the use of prescription drugs for the disorders. They also complain about the financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry among some of the clinicians responsible for drafting the revision.

Unfortunately there is no simple solution to this dilemma. The research universities and pharmaceutical companies working in psychiatry and addiction medicine all want the top researchers and clinicians, and so does the American Psychiatric Association (APA), which publishes the DSM. There is an imperative in our field to continually assess treatment outcomes to develop better data about whichinterventions are most effective for which patients under which circumstances—and this responsibility is shared by all of us in the treatment community, including the companies that make the drugs.

Critics with a more theoretical approach have a closely related concern: that the new DSM will reflect psychiatry’s focus on the biological (at the expense of the psychosocial) basis of mental disorders. That the APA leans toward biology is to be expected. Trends in the profession favor an increasingly medical viewpoint, with a growing appetite for the view that, as Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Dr. Nora Volkow says, “addiction is a brain disease.”

In fact, the default response to most psychiatric illness in the US is increasingly pharmaceutical. Whether or not it makes sense to have the APA produce the document that ultimately drives treatment dollars is another, larger question.

Yet the success rate of addiction treatment is so low partly because the “disorder” that comes into the consultation office is all tangled up with the patient’s entire entourage of circumstance and injury. Decisions about appropriate treatment should be based on a combination of factors, including addiction severity, other mental illness, pre-illness personality and collateral damage to the patient’s world.

Chronic drug use changes the chemistry of your brain, no doubt, and maybe for a long time. But trying to reduce the complexities of an individual’s addictive behavior to a “brain disease” doesn’t fully capture it, not even close.

Most clinicians who believe that addiction and many other mental disorders are primarily rooted in psychosocial influences argue not that medications are not useful but that they should be temporary aids as opposed to solutions. I count myself in this nurture school, which emphasizes that the insights, skills and growth that can occur in psychotherapy can be used by the patient long after the treatment episode ends.

As in other areas of psychiatry, there are pharmacological interventions in addiction medicine that are highly effective and useful in treating substance use disorders, an arsenal that now includes newer medications such as buprenorphine and naltrexone. These medications can be an indispensable part of the treatment plan for some patients, and we should continue to look for innovation from all directions: planning overall episodes of care, refining psychotherapy techniques and creating new drugs. Addiction is one of the most devastating and costly afflictions on the planet. We can’t afford to prejudice ourselves against any useful or promising treatments.

On balance, I disagree with those who are alarmed by the proposed changes in DSM-5. To my mind, changes that more accurately recognize the complexities of addiction and encourage robust treatment are more than welcome. The fact that binge drinking is so pervasive among college students and other young people indicates not that it is the norm, and therefore OK (not a problem), but that it is a very big problem indeed. Arguing otherwise is like saying that since so many Americans are obese, it needn’t be addressed because it is a cultural norm.

Among the millions of people who will be diagnosed with an addictive disorder in the new DSM are many whose lives will be derailed by their substance use, leading to car accidents, suicide, brain damage, sexual trauma and a host of less severe outcomes. The new criteria will allow clinicians to intervene at an earlier stage in the addiction cycle, when relatively brief and inexpensive treatments can prevent more serious problems from escalating. Psycho-education, psychotherapy and group support should be available for people who seek treatment early on. Who would argue that it’s better to wait until the substance use escalates before treatment can be initiated?

As for the inclusion of cravings and urges as diagnostically legitimate, this is an important step forward because it recognizes the unique patterns and complexities of addiction’s actual clinical picture. One person might suddenly find himself pounding down shots at a bar or relapsing with cocaine without ever having consciously grappled with a desire to use. Someone else will carefully inventory and explore his urges, triggers and “close calls” prior to relapse. Again, I believe that somebody in this situation is an excellent candidate for treatment geared toward relapse prevention.

I think that including gambling in the broad category of addictive disorders is clinically valid. All addictions involve a pathological development toward behavior that is increasingly compulsive and restricted. Classifying Gambling Disorder as an addiction is a step toward acknowledging that a range of behaviors can become out of control. Obviously, alcohol and drugs act directly on the brain, creating an unmediated effect on pathways and regions that are implicated in addiction. This may make them especially resistant to amelioration. But excessive or maladaptive patterns of gambling, sex, internet use, eating and other activities can cause diminishment and distortions of experience in a way that mirrors substance use disorder. A substance is not a prerequisite for an addictive disorder.

In the end, all addictions can be devastating. Changing the diagnostic indicators will not drag people unwittingly into treatment or dictate the approach that a given provider will use. The most significant likely consequences of the revision of the diagnostic criteria are expanded and earlier intervention and treatment. In the long run, these are benefits that will prove not only lifesaving but cost-effective. Who can argue with that?

Please let us know what you think of the DSM-V revisions to the addiction diagnosis by posting a comment below.

Richard Juman is a licensed clinical psychologist who has worked in the field of addiction for over 25 years, providing direct clinical care, supervision, program development and administration across multiple settings. A specialist in geriatric care and organizational change, he is also the president of the New York State Psychological Association. His email is dr.richard.juman@gmail.com; he tweets are twitter:@richardjuman