I forced myself to look at my husband’s feet. They were coal black. His toes looked so dry and brittle that I thought they would snap off if I touched them. The last time I’d talked to him was 16 days ago when the nurse with the thick Queens accent who jokingly called herself Ratched had covered me in full surgical garb and wheeled me briskly past the security guard stationed outside my room to the ICU.

My big, burly, mountain-climbing, life-of-the-party, trial lawyer husband with his deep Texan voice muffled behind an oxygen mask asked me to rub his feet while a doctor gently tried to explain that they needed our permission to perform a procedure so that John’s organs could rest. Now I faced a horrific life or death decision from which there would be no escape.

John and I had been rushed to the emergency room two weeks earlier with a preliminary diagnosis that instilled fear and panic throughout the corridors of a small Manhattan hospital. We had spent two fitful nights in a hotel room fighting intense fevers, chills, aches and extreme exhaustion before admitting to ourselves that we did not have just the flu. The painful, red-hot swelling in my groin area had grown crippling and proved to be the one symptom that led a travel doctor, well versed in global esoteric diseases, to our diagnosis. Pulling a medical journal off his shelf, he pointed to a photograph of a seeping tumor. “See, this is what you have. A bubo.”

He meant bubonic plague, the scourge that wiped out Europe in the 14th century and was supposed to be as ancient as horse-drawn carriages. Only about seven cases are reported in the United States annually, mostly in northern New Mexico, and New York City had not seen an instance in more than 100 years.

This was back in 2002, and checking into a New York City hospital barely a year after 9/11 for treatment of one of the top seven bio-terrorism diseases will get you quick attention. I was immediately given large doses of powerful antibiotics, felt well enough to choke down a dried-out tuna sandwich in the wee hours of the first night and limped out of the hospital 10 days later with only lingering pain from my then dissipating bubo. I call mine a “sissy” case of the plague.

John, however, was much sicker, as dozens of doctors, health department officials, CDC authorities and even FBI agents explained to me during interviews in my hospital room. Where had we been before coming to New York City? What exactly had we been doing? Why would John be so much more ill? An investigation of our backgrounds and a thorough search of our home in Santa Fe convinced the authorities that we were neither victims nor perpetrators of bio-terrorism, but simply one unlucky couple who had most likely been bitten by an infected flea while hiking near our home.

John, in the meantime, was just starting a battle for his life in a drug-induced coma with less than a 1 percent chance of survival. Through the following days and nights spent at his bedside, I became conversant in terrifying, previously foreign terms like “acute respiratory distress syndrome” and “disseminated intravascular coagulation.” I hadn’t really known what a platelet was or how to spell it. I had never seen someone on advanced life support. I had never listened to the beeping, dinging, heaving sounds of a myriad of medical machines, lines and tubes. I could not even imagine gangrene.

John had septicemic plague. His body was suffocating with multiplying infections. Infectious disease doctors battled new invasions to his bloodstream minute by minute, declaring victory over one only to face another. I watched them wearily rub their foreheads as they thumbed through a voluminous book called his chart, desperately searching for another antibiotic. In spite of their herculean efforts, John’s fever remained dangerously high, his organs continued to fail and the Black Death crept into his hands and feet.

On a brisk November afternoon, one of New York’s most renowned vascular surgeons came to meet with me outside of John’s room to talk about what I knew in my gut, but what my head and heart desperately tried to deny — amputation. The doctors had decided that the only way to give John any chance to live would be to perform what they called a guillotine procedure at his ankles and allow the wounds to remain open for a period of time. The decision was mine.

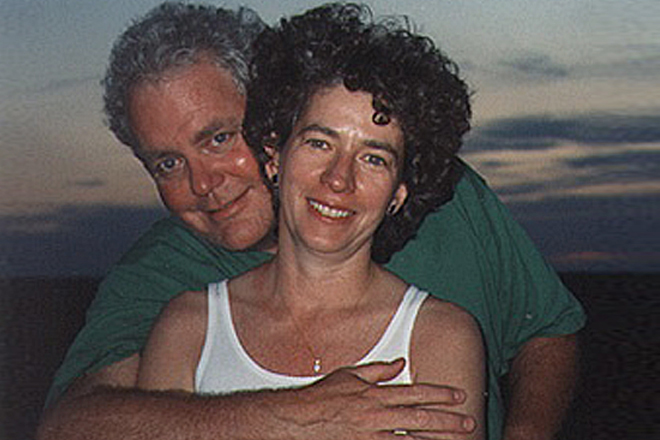

Eyes the color of mountain bluebirds that swarm our feeder in the winter, a mop of curly gray hair, a voracious appetite for books, keen intelligence, curiosity and a streak of bullheadedness that refused to give up an argument or give in to an outdated disease. My best friend, whom I longed to laugh with about the stir he had caused in world news and who had a first grandchild on the way.

There would be no late-night hand-wringing, agonizing or second-guessing. I would do everything in my power, I would spend every waking moment and make every decision I faced in the next 10 weeks focused on one goal: to look into those eyes again. In mid-January, I did.

My plan was to have an army of doctors and psychologists at his bedside when he awoke. How do you tell someone you love that he has been in a coma for over two months, that he missed Thanksgiving and Christmas, that it is a new year and he no longer has legs? He could not speak or move. His first words to me, mouthed in a faint whisper, “Rub my feet.” I told him then, on my own, what had happened as I gently massaged what remained of his legs.

John is the only person in medical history to survive an advanced stage of septicemic plague. While in a coma he had endured brain-blistering fevers, rampant infections, numerous surgeries, and massive doses of medications toxic enough to permanently damage his hearing and nearly end his kidney function. It was anyone’s guess as to whether his brain would be intact. Outside of a couple weeks of untangling some pretty thick cobwebs and one scary ICU psychotic episode, the man I knew and loved slowly came back to me.

The loss of his legs and the disappearance of so much time were almost equally difficult for John to process. We distracted ourselves from dwelling on the pain of what we had been through by planning the near future: which long-term rehab hospital would be best, what air-ambulance company would fly us back to our beloved New Mexico. John’s positive outlook came back in full force. “I just had my first out-of-foot experience,” he said with a hint of a smile one morning.

Just before Valentine’s Day I packed us up to head to Teterboro Airport. It was a blessing that we had little idea of the long road ahead of us, of the months of painful rehab to learn to speak and swallow, to take a first step. We did not fully grasp then that everything would be different; that our lives were forever changed.

What we knew was that we had our lives. We knew that Nurse Ratched and the team of nurses, doctors and therapists who gathered around that morning to bid us farewell and good luck had gotten us to this place. We were leaving the small hospital that had begun to feel like home, together.

John lifted up his left hand, the only part of his body he could move, a few inches off the gurney and waved goodbye.