The opening scene of Marcel Proust's "Swann's Way" is one of the most famously difficult to get through in literature. That's not because of its style, which is sublime, but because it describes the experience of falling asleep. Many susceptible readers nod off the first few times they attempt it. All writing about sleep has this problem; of the fundamental human appetites, it's the least exciting. The better you invoke it, the more likely you are to incite it, and because it can't be remembered, sleep can't be described. Nothing could be duller than watching someone else do it. Only people who can't sleep spend much time thinking about it, and if there's anything more tedious than witnessing another person's nap, it's listening to a keyed-up, obsessive insomniac go on and on about how they can't.

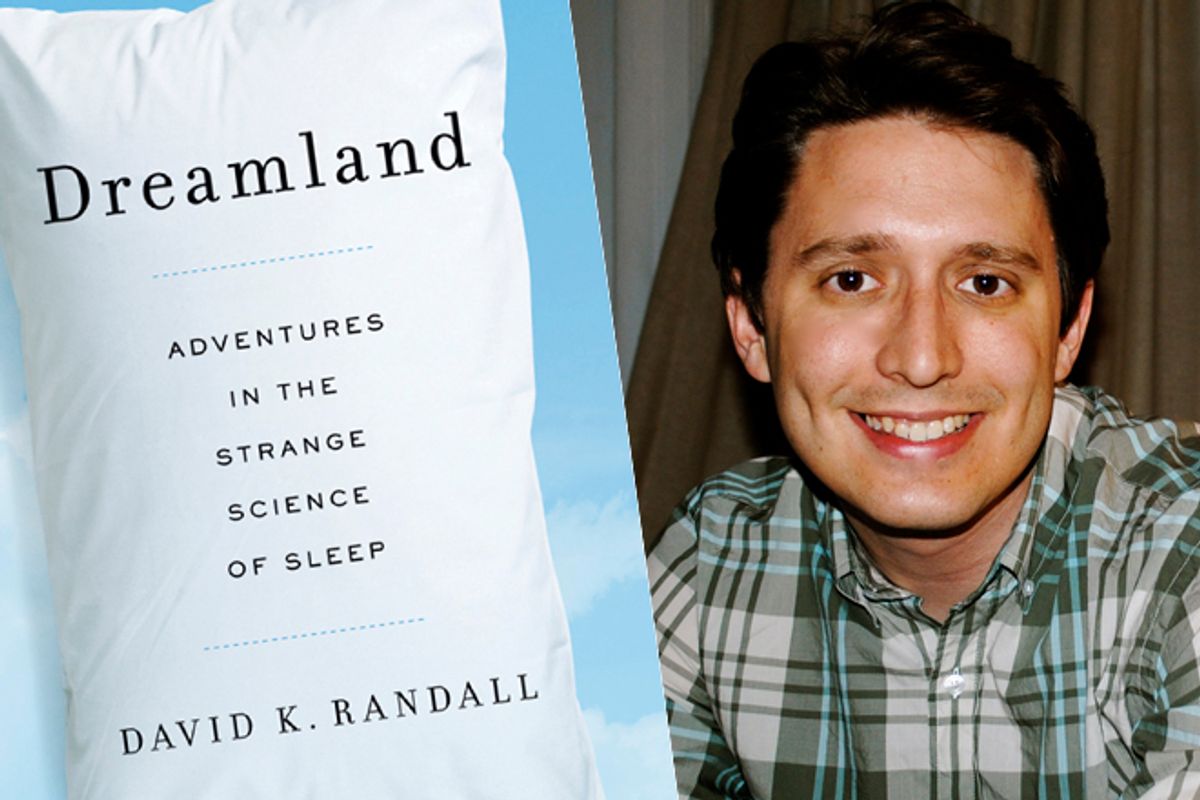

So kudos to David K. Randall for writing what must be the most diverting and consistently fascinating book on the topic ever, "Dreamland: Adventures in the Strange Science of Sleep." I feel I can speak with some authority on the subject because I've read quite a few sleep books in my time. My interest arises from my own mild parasomnia, or sleep disorder, one that runs in my family. We talk and sometimes walk in our sleep. Randall suffers from the same condition, although of the two of us, he's the only one who's truly suffered from it. A few years ago, he hurt himself when he collided with a wall while sleepwalking. It was the first time (he knows of) that he'd ever walked in his sleep, but every night his wife curls up at the far end of their "oversized" bed, wearing earplugs to shut out his "talking, singing, laughing, humming, giggling, grunting." Also, he kicks.

If there's anything creepier than hearing someone laugh in their sleep, it's got to be another of Randall's propensities; he can fall asleep with his eyes open. We deduce, therefore, that his wife is a woman of fortitude, but the sleepwalking incident freaked her out properly. She insisted he seek treatment and Randall visited a sleep lab. An uncomfortable night spent with electrodes taped to his head elicited the observation "you certainly kick a lot" and not much more. Randall learned that "sleep is one of the dirty little secrets of science." We don't know as much about it as we should, or could.

Hence, "Dreamland," a book that cleverly approaches a spectrum of sleep-related issues from the worst-case-scenario perspective. If you want to know how serious the problem of sleep deprivation can be, look at the U.S. Army, which is only just coming to terms with the role lack of sleep plays in the 25 percent of American combat deaths resulting from friendly fire. During the occupation of Iraq, soldiers sleeping less than four hours per night reported five times as many altercations with civilians as those who had the full eight. Lack of sleep impairs a person's ability to make decisions, communicate with others and improvise effectively. Well, we all know that, don't we? But learning how much blood and good will has been squandered as a result of macho attitudes toward soldiers' sleep needs (four hours a night -- for hardworking 20-year-olds -- really?) is sobering.

Randall explores the significance of circadian rhythms -- the body's internal clock, which "tells an organism when it is time to perform an important activity and when it is time to rest" -- by looking at the lives of professional athletes. Stanford sleep researchers, he relates, demonstrated that East Coast football teams labored under a permanent disadvantage in Monday night football games. The games were always scheduled at 9 p.m. EST, no matter where they were played, to maximize television viewership. The average human body will "perk up around nine o'clock in the morning and stay that way until around two in the afternoon, which is when we start thinking about a nap. Around six in the evening, the body gets another shot of energy that keeps us going until about 10 at night." A three-hour jet lag may sound minor, but it meant that West Coast teams always played at what their bodies thought was 6:00 p.m., a peak in the cycle, while their East Coast opponents played at a time when their bodies were winding down. The point spreads reflected the difference.

Perhaps the most bizarre material in "Dreamland" concerns sleepwalking, and specifically the responsibility a person has for any crimes he commits while asleep. It happens. If most sleepwalkers are like me -- barely able to bumble across the room before waking ourselves up -- a rare, unlucky few have been known to perform complex actions, like cooking or driving a car, while unconscious. In 1988, a 23-year-old Toronto man was acquitted of murdering his mother-in-law while asleep. Randall notes that "parasomnias seemed to be a particularly male trait," but I suspect that men, who are more prone to aggressive dreams in the first place, are more likely than women to engage in sleepwalking that presents a threat to others. Attempting to strangle one's bed partner because you think he or she is an attacker is a classic example. Less dangerous forms of sleepwalking, like my own, simply don't get reported.

The most unusual thing I've ever done in my sleep is write a letter -- although I'd only managed the salutation before the difficulty of the task woke me up. The next morning, the handwritten evidence of this incident spooked me. It was like a message from a stranger I could never meet, but who just happened to inhabit the same body. Whether I could be held responsible for this stranger's actions isn't a question I've ever had to face, but it's the kind of quandary that courts, legal scholars and a handful of neurologists have had to wrestle with. One expert Randall interviews advocates a new classification for such crimes: "semi-voluntary." If the culprit knows he has a problem and doesn't take measures to control it, he holds at least some responsibility for the results.

The concept of an unconscious mind has fallen out of intellectual favor, associated as it is with largely invalidated Freudian models of the self. Yet some of the sleep-related subjects Randall covers in "Dreamland" do touch upon this territory, from dreams to the many accounts of people who, after having pondering a persistent problem, suddenly woke up with a fully formed solution. Paul McCartney wrote the hit song "Yesterday" in just this way.

It appears that, while asleep, the brain sorts through the day's events and lays down long-term memories, an administrative process that Randall describes as "cleaning up and organizing the mind's filing cabinet." This does not at all resemble the highly symbolic theater that human beings have imagined the dream landscape to be for millennia. However, in a later sleep stage, once the initial tidying is over, the brain begins "finding connections and associations with the data embedded in its memory cards," a creative activity that looks an awful lot like thinking. This makes the idea of an unconscious self seem less obsolete.

"Dreamland" covers an abundance of other slumber-related issues, from sleep apnea to the importance of mattresses (which is negligible) to the interesting fact that most people sleep much better alone. It's all weirdly fascinating, which -- trust me -- is a testimony to the lively curiosity, solid research and inventive angles that Randall brings to each aspect of his subject. You almost certainly don't sleep the way you think you do. There's much evidence to indicate that people are the worst possible information sources when it comes to their own sleep habits. That's not surprising when you consider that they're unconscious for most of it. It's remarkable to think that such a mundane activity should still be shrouded in so much mystery, but you couldn't find a more charming guide to what we do know than "Dreamland."

Shares