You have turned to evolutionary biology and anthropology to help understand the development of economic institutions and behaviour. Why are they important in helping us get to grips with today’s complex and fast-moving world?

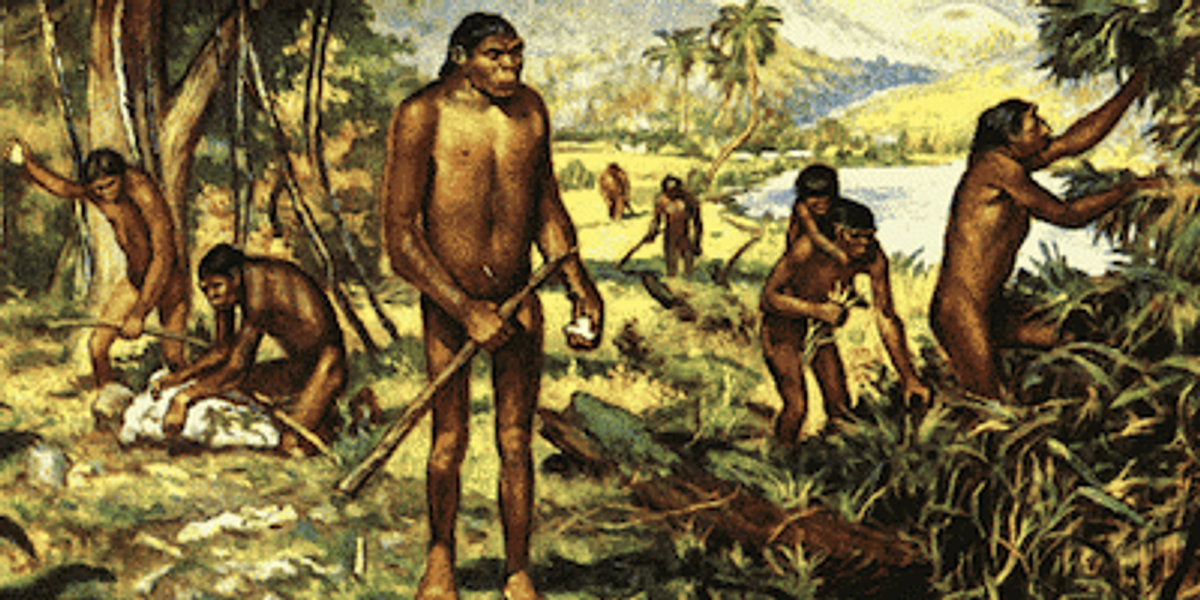

They are important because we are a species like any other and have this wonderful construction, which is the society we’ve built. It’s as wonderful, or more so even, as the extraordinary nests built by ants and termites or the incredible song and other behavioural patterns of birds. I’ve always thought that if we take animals seriously as producing behaviour and not just bodies, then we should do the same for ourselves. We should see our behaviour as coming out of the constraints of our environment and the adaptations that have developed in the history of our species.

It used to be fashionable to think that genes, and indeed the process of natural selection, affected our bodies but not our minds. We’ve come to realise that that’s untrue and that our minds are profoundly shaped by natural selection – even if the environment we now live in is massively different from the one in which most of that evolution took place. So you can learn a lot from the fact that our minds are not just any old general purpose computer. They are actually shaped by evolution, though we have to remember that the circumstances in which we evolved are startlingly different from the circumstances in which we now have to navigate.

The world has got a lot more complex in the last 100 years or so and human minds have to process ever larger amounts of information. Are they evolving fast enough to deal with it?

No, in some ways they aren’t. A very good example is the way in which we process a lot more digital information now than we used to – we read a lot more text. People sometimes say we are completely overwhelmed with incoming information in the modern world, and that’s true. But in a certain sense our hunter-gatherer ancestors were also overwhelmed with incoming information – they would be sitting around their fires with their senses very carefully tuned for predators, for example. They would also take in information about their environment with a tremendously high bandwidth, in terms of how they judged their fellow human beings as being hostile or friendly, reliable or untrustworthy. Natural selection produced a number of mechanisms that helped them deal with that bandwidth. For example, we know we have these abilities to size up people’s faces with extraordinary speed and sophistication – we can tell just from the location of the white of somebody’s eyes who they are looking at, and whether their relationship with people around them is dominant or submissive, aggressive or defensive, competitive or collaborative.

In the modern world we can still do all that sort of thing rather quickly, but a much larger part of the information comes in the form of text, some of which we deal with using a part of the brain called “working memory”, which has a much lower bandwidth. For example, the standard idea is that you can hold about seven to nine items of information in working memory at one time. That’s enough to remember somebody’s telephone number, but if you try to remember somebody’s telephone number and try to do something else that requires textual manipulation at the same time, you are very quickly overwhelmed. That’s a good example of how natural selection shaped the brain for the kind of tasks that we needed to do in the Pleistocene but didn’t – for obvious reasons – foresee the kinds of tasks we would have to do in the 21st century.

The extraordinary capacity of humans to cooperate is a big theme of both your books "The Company of Strangers" and "The War of the Sexes". Where did this ability to cooperate come from?

The first thing to bear in mind is that cooperation is in some sense a natural ability. That doesn’t mean that it’s an ability that comes to us without any difficulty. It means that our ability to cooperate is part of nature – it’s not something that’s been grafted artificially on to our natural tendencies. It’s important to stress that because for a very long time – particularly in my discipline of economics – it was assumed that what was natural about human beings was selfishness and competition, and that any ability we might have to cooperate was an artificial and fragile construct. But that doesn’t makes sense of the fact that cooperation is very widespread in nature, even if humans have taken it to a level that far exceeds anything that we find in any other species.

So I first wanted to show that cooperation was a natural talent and therefore something we could learn about by looking at how our natural talents have evolved. But secondly, to emphasise that it’s a natural talent that’s being exercised in a very different setting from the way it used to be exercised. In The Company of Strangers I argue that we are like a species that’s navigating out to the open sea having only evolved to move about on the land. Just as you can learn how to swim from understanding the ways the limb works, even though the limbs evolved in a different environment, similarly we can understand something about the strengths and weaknesses of our cooperative tendencies in the modern world from understanding how they evolved, but without mechanically extending our analysis of how they worked in the Pleistocene to how they work today.

Let’s look at your book selection now. Is there a common thread?

All five books are about the way in which cooperation is natural to us and the way in which we can learn about its strengths and its weaknesses from features of its evolution. There’s one big book missing that in a way underlies all of my choices and to which all of them, in their own way, pay homage. That’s Charles Darwin’s "The Descent of Man". Darwin was very cautious in his book "On the Origin of Species" not to draw any explicit conclusions about human society. It wasn’t until The Descent of Man that he really talked about human evolution. For Darwin, sexual selection was absolutely crucial to understanding why human society operated the way it did. The relationships between the sexes, which for Darwin were both cooperative and competitive, symbolised perfectly the tension between cooperation and competition at the heart of modern life.

The central message of "The Descent of Man" is that cooperation isn’t contrary to nature. Contrary to the idea that some people have, that natural selection selects purely for selfish qualities, Darwin was quite clear that natural selection can select for cooperative and collaborative qualities. But he also points out that the process of selection for cooperative and collaborative qualities is not a serene parade of agreeableness – it’s the result of often violent conflicts. It’s because we live in a world which often has violent conflicts that our collaborative qualities are so important.

The "Origins of Virtue" was published in the mid-1990s and argues that cooperation and virtue are just as deep-rooted in human nature as selfishness.

Yes, exactly. In one sense Matt Ridley was restating the message which was already there in The Descent of Man but which had rather been forgotten. What this book did was popularise the idea that cooperation can indeed be favoured by natural selection.

This book is a great read because it takes all sorts of examples from history and from everyday life and brings in pieces of economic analysis like the prisoner’s dilemma, which are by now quite well known. It also adds insights from biology – for example, the competition between maternal and foetal genes in the uterus, which not everybody will know about. Nearly 15 years after the book was published, I can still reread it with enjoyment and still gain insights. In a very fast changing field of research, it’s quite a triumph for a book to remain entertaining, enjoyable and insightful so long after it was first published.

Matt Ridley does have his critics, especially of his more recent book "The Rational Optimist," who argue that he is too simplistic and optimistic about human evolution, seeing it on a continual positive upward trajectory.

I think that’s a partial description of his book. My sense is that Ridley has his critics partly because he can’t resist launching torpedoes at his pet hates, which include naive environmentalists and such like. He can sometimes come across as this grouchy individual muttering on about political correctness gone mad and I think that assumed persona does indeed annoy some people. It doesn’t annoy me because I can read past it.

I think the best analogy that applies to Ridley’s "The Origins of Virtue" is with doctors studying the human body. If you want to understand disease and the pathologies the human body is susceptible to you won’t get anywhere unless you have some deep respect for the amazing things the human body can achieve. It’s not until you understand what a remarkable construction the human body is that you can really understand its pathologies. And so it’s not until you can understand what an extraordinary development human cooperation is, and the remarkable things it has achieved, that you can properly get an insight into its continuing fragilities. Yes, Ridley tends to put a lot of emphasis on the remarkable achievements, but I don’t think he’s at all blind to the fragilities of modern society.

On to your next pick now, which one reviewer has described as “a compelling and novel account of how humans come to be moral and cooperative”. Please tell us more.

For a long time the puzzle of cooperation in modern societies was posed as: How can selfish individuals come to cooperate? This book – which again is clearly in the tradition of Darwin’s The Descent of Man – says that this question is mis-posed because the evidence is overwhelming that human beings are not entirely selfish. They are motivated by lots of other things like sympathy, altruism and mutual affection, and also by envy, revenge and resentment. Bowles and Gintis argue that that puzzle is rather how natural selection came to make us not entirely selfish. How did these complicated humans – who certainly have selfish motives but also motives of sympathy, affection, resentment and envy and so forth – come to make it through the process of natural selection? So the book is largely about this question, which they argue is the really difficult one to answer.

This is a more academically rigorous book. By saying that I’m not signalling that it’s an impossible read – on the contrary it’s a very good read – but some of the chapters are rather technical. I would encourage readers who are worried about technicalities not to mind that, as you don’t have to read every chapter in the book in order to come out of it inspired and informed.

"Hierarchy in the Forest" addresses the question of whether humans are naturally hierarchical or egalitarian. I guess the answer is a bit of both, isn’t it?

Yes, indeed it is. Boehm starts from the paradox that we share a common ancestry with apes and monkeys who live in very hierarchical societies, and that today we live in pretty hierarchical societies, but that all the evidence suggests that in between the two we went through a period of existence as hunters and gatherers in societies which were remarkably egalitarian, with very little stratification of wealth and other resources. Boehm wants to know why.

So the question is: Did human nature change in the interval? For a long time Jean-Jacques Rousseau sold the world a vision of society before modern civilisation, which suggested that human beings were naturally egalitarian and that it was only some corruption of modern society that had made it hierarchical. Boehm shoots down that view quite comprehensively and replaces it with a much more compelling story. In his picture, which is meticulously researched, the desire for status and competitiveness was no weaker in forager societies than it was with their great ape ancestors and than it is in modern society. The crucial thing is that in forager societies it’s counterbalanced by an equally strong – and in his view a distinctively human – talent to form coalitions to restrain the tendency of successful individuals to abuse their success. So, according to Boehm, everybody in a forager society wants to be successful and indeed has an intense sense of relative status and competition with others, but if any warrior gets too big for his boots he provokes a defensive coalition of the beta males who will ensure he is restrained and if necessary punished – to the point of being excluded or killed if he abuses the privileges to which his success gives him access. The beta males can achieve this because the powerful males need them in a forager ecology, unlike, say, in agricultural societies, which can rely on coercion and slavery.

So Boehm’s vision of an egalitarian society is a much more realistic one. It’s not that everyone acquires this soppy desire to be equal to everybody else. Everybody remains as status conscious and competitive as they ever were, but they are also acutely aware of the dangers of abusing the privileges to which the acquisition of status might give rise. That’s something he documents as a remarkable human talent. I think Boehm’s book reconciles bourgeois society to the criticism that Nietzsche made of it, which was that it was a slave morality – according to him, modern bourgeois society enthrones the morality of the weak against the splendid instincts of the strong. Nietzsche meant that as a criticism, but in some sense Boehm is saying that it’s not a criticism. It is what makes modern society possible – the dashing and the strong are kept in check by the instincts of the rest of us.

Can we find some examples in modern life – perhaps in the sacking of top bankers or in political life?

A very good example is of political leaders, where the processes that Boehm describes are beautifully illustrated. We go through this very dysfunctional process by which we all desperately want to believe in a leader, a warrior if you like, who will lead us out of our current doldrums. So we elect a warrior whom we briefly regard as a hero, and then we all start muttering in corners that he has feet of clay. I think this partly explains the depressingly masculine character of so much of political life. We want a warrior figure but then we start complaining about his failings. We bring him down to earth by deploying everything Nietzsche complained about as being the slave morality. Boehm reminds us that these are two inextricable facets of the way we treat our leaders. We want our leaders to both solve all our problems for us and not get above themselves. Boehm believes we’re asking the impossible.

De Waal is a primatologist and ethologist and in "Peacemaking Among Primates" looks at how different types of simians cope with aggression and make peace. What does it tell us?

De Waal came to fame in an earlier book "Chimpanzee Politics," which reminded us about something very important in many primate societies. This is that although such societies are intensely competitive, they are as much about competition between coalitions and groups as they are about competition between individuals. In a group-living primate society any individual is engaged in a complicated balance between trying to cooperate with some individuals but at the same time competing with those individuals against other groups of individuals – and competing to be accepted by the coalitions that are powerful. This explains some of the tension between the cooperative and competitive instincts that we feel simultaneously when we’re in complex societies.

"Peacemaking Among Primates" says that fighting and reconciliation are not incomprehensible pathologies of modern society. This book reminds us that we do have evolved talents for fighting and for making up after we have fought. Given how often we fight, it would be astonishing if natural selection hadn’t given us some talent for dealing with that. In De Waal’s picture, the cycle of fighting and reconciliation should be understood as the exercise of evolved talents rather than just an inexplicable breakdown of something that ought to be operating more harmoniously.

I think that’s the general message of this book and it’s a wonderful book for that reason. But I also love it for a reason related to my recent book "The War of the Sexes," because it talks a lot about the different ways male and female primates build coalitions. He has a lovely study of the way in which male chimpanzees, when they meet up with each other, have a very high probability of fighting. But after they fight, they make up rather easily. His observations of female chimpanzees suggest that it is much rarer for them to fight – they are much more loyal to each other and their coalitions are much more stable – but when they do, it is also much rarer for them to make up. In my book I don’t make simplistic comparisons between the characteristics of chimpanzees and humans, but the idea that there may be gender differences in coalitional behaviour is not far-fetched. I describe pieces of evidence that suggest it may be an important phenomenon.

I don’t think we can move to the next book without mentioning the bonobo who opts to make love not war – resorting to sex rather than violence to resolve tension.

Bonobos are fascinating for all sorts of reasons. They do appear to be much less violent than their close cousins the chimpanzees, because they use sex as a diffuser of aggressive impulses in a way that is rarer among chimpanzees. It’s a general reminder that sex in many animal species has adaptive benefits that are not just to be understood in terms of the offspring that result from sexual encounters. The idea that sex can serve to cement friendships and coalitions is a very important part of the adaptive consequences of sexual activity. It’s one reason why there’s no mystery about the evolution of homosexuality, because homosexual relations – which the bonobo enjoys with exuberance – might not result in offspring but they do have consequences for the making of coalitions and friendships in a group-living species. Those coalitions and friendships have very important adaptive consequences.

Sarah Hrdy examines maternal instincts and has conclusions that seem very relevant to the modern workplace. Please tell us more about your final pick, "Mothers and Others."

This book shows us that mothers do something that is absolutely central to the great human talent – they are consummate coalition builders. Sarah Hrdy is a great primatologist and feminist. There has often been unease in the feminist movement at the idea that our biology should ever play an important part in understanding who we are as men and women. Hrdy has done more than any other individual to bring a sophisticated understanding of biology to the heart of a feminist perspective that we can live with in the 21st century. What she emphasises is that the old idea that human beings were fundamentally pair-bonded and that women were permanently shackled to men for the whole of their reproductive life, needs to be nuanced by an understanding of how women actually construct the coalitions that provide care to their offspring.

She reminds us that human offspring can be handled socially in a way that’s completely impossible for other primates. You can go to a mother whose baby was born recently and take the baby out of her hands and pass it around a circle of admiring family and friends without the mother going crazy. You try doing that to a female chimpanzee and you’ll be lucky to escape with your life. There’s something really powerful about the idea that human childcare is a collaborative process in which the mother is not the only person who looks after the baby. She is at the centre of a large coalition of individuals who all do their bit. This coalition can include the biological father, but it doesn’t have to. Just as important are siblings, cousins, grandparents, uncles and aunts. Sarah Hrdy tells us that human childcare is a powerfully collaborative group endeavour. It’s not just about mothers on their own and it’s not just about pair bonds either – it’s about a whole team that brings the human baby into adulthood.

She describes humans in the book as “cooperative breeders”. On a more practical level, I suppose it’s saying that women shouldn’t feel guilty for leaving the care of their babies to others when they return to the workplace.

The point is that modern mothers who are juggling the demands of different activities and arranging childcare aren’t doing something unnatural, they’re doing something profoundly natural. She also reminds us that the fact that it’s natural doesn’t mean that it’s free of tension. In her picture, as in Darwin’s, cooperative breeding isn’t a serene parade of agreeableness – it’s a tense, stress-filled activity. But the point is that we are creatures that have evolved to be used to tense, stress-filled activity – that’s what human cooperation is like. People who fantasise about human social life as being either about unremitting competition, or about collaborations that are entirely easy and stress free, have missed the point. Human society is profoundly collaborative but that doesn’t make it stress free.

Shares