Poke around the White House website and you can still find the hopeful "fact sheet" for a 324-mile high-speed rail line linking Miami, Orlando and Tampa.

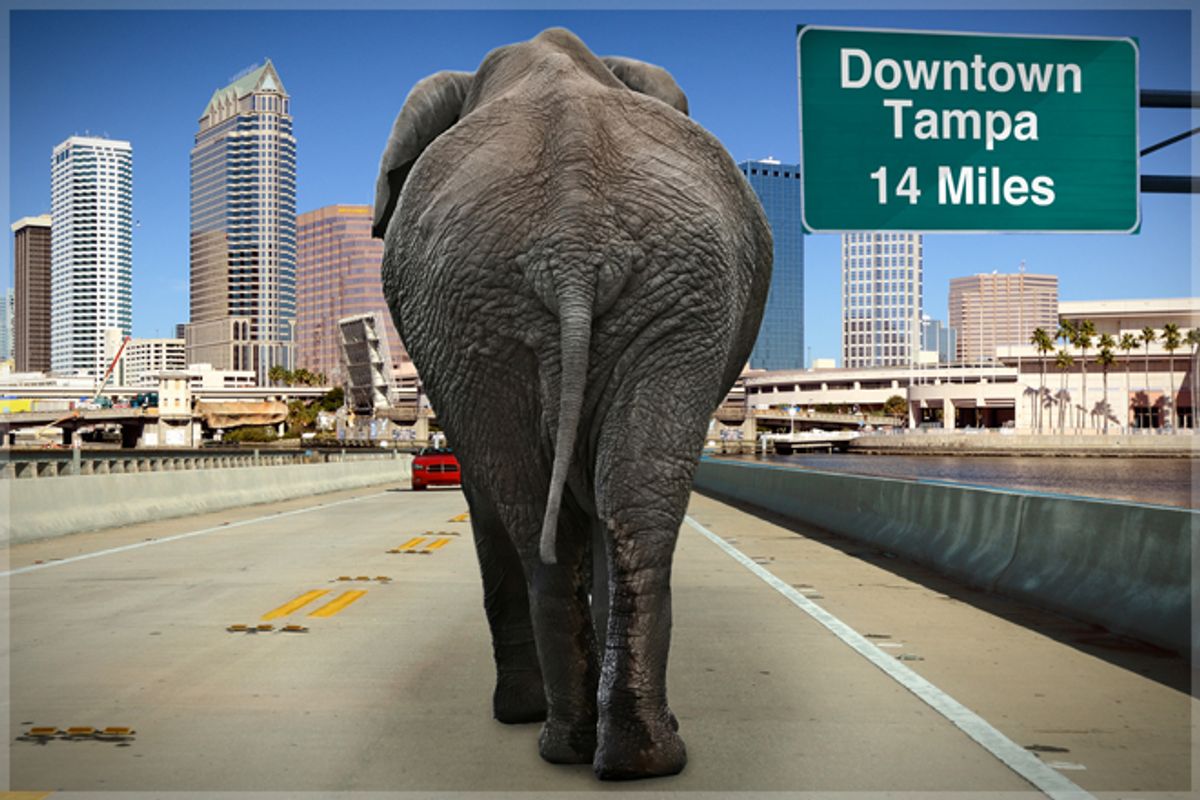

No such system exists, of course -- it was killed by Florida Gov. Rick Scott. Today, there's a 40-acre vacant lot where the Tampa terminal would have stood. And when Republicans arrive for their national convention in about a week and catch a glimpse of it, they'll likely see a big win. In fact, the GOP will find a lot of things in Tampa that exemplify their commitment to not investing in the future.

"The trend [in Tampa] today is to say, 'We don't need it -- no new taxes -- we are not going to invest anymore,'" former Pinellas County Commissioner Ronnie Duncan recently told Tampa Bay Online. "And that message resonates from not only the constituents, but the leadership of the Republican Party." You could fairly call the GOP vision for the country the Tampafication of America.

Tampa is a hot urban mess, equal parts Reagan '80s and Paul Ryan 2010s. Urban renewal projects decimated the city in the '60s, but its current persona was forged in earnest starting three decades ago, when finance and insurance companies started moving their back-office operations there, attracted by the sunshine and low-cost labor. The 1988 bestseller "Megatrends" declared Tampa "America's next great city." Real estate joined the service economy as a major economic pillar, and the city embarked on a building spree, sprouting large glass towers disconnected from the city itself, a development pattern that offered little incentive to invest in things like parks, transit or walkable spaces.

This left little of the quality urbanism people now pay a premium for. And while other cities made similar mistakes, Tampa has been slow to correct theirs, stymied by tight-fisted Tea Party politics. "We look at Dallas or Houston, with all the same challenges we have; they've managed to start changing their patterns of development and attract the creative-class younger folks who are looking for alternatives to the suburban lifestyle," says Steve Schukraft, the Tampa Bay area's representative to the Congress for the New Urbanism. When you're wistfully pining for Houston's urban virtues, things are not going well.

But that's where Tampa finds itself. Even Houston, like other Sun Belt cities, has been working to rectify its mistakes, constructing successful light-rail lines and some lively mixed-use neighborhoods. Meanwhile, in 2010, voters in Tampa's Hillsborough County rejected a one-cent sales tax that would have funded a new light-rail system. (That same year, the Tampa Bay area saw the nation's largest increase in traffic congestion.) Fifty percent of the urban core is now set aside for parking, says Shannon Bassett, assistant professor of architecture and urbanism at the University of South Florida.

These choices have left their mark. In 2010, Forbes ranked Tampa dead last out of 60 metro areas for commuting. Transportation for America declared it the second-most-dangerous city for pedestrians. And a 2007 survey of 30 metropolitan areas found exactly one with no walkable destinations: Tampa, Fla. "Tampa is not a particularly pedestrian-friendly city," Mayor Bob Buckhorn recently admitted.

Bassett is working to "de-engineer" the city from this current state. "How do you address the lack of pedestrianism, the lack of civic space, the lack of shade, which is crucial for Florida urbanism?" she asks. "There's some bike paths now, and landscaping, but to me it's not integrative. I think it needs a larger rethinking of its infrastructure. It's operating in more of an '80s mentality."

But de-engineering isn't easy in a city with an aversion not only to public spending, but urban planning. Tea Party paranoia includes a bizarre fear of smart-growth policies, in which more intelligent land-use management is seen as a shadowy United Nations conspiracy (complete with a scary-sounding name: Agenda 21). And while the city of Tampa might not be hard-right politically, Hillsborough and Pinella Counties, which control many of the decisions that affect it, are bona fide birther territory. "The county commission is much more conservative now than it was in the late '80s, early '90s," says Robert Kerstein, who teaches the city's history and politics at the University of Tampa. "They have a strong religious-right orientation."

One of their commandments is Thou Shalt Not Densify. Sprawl is gospel in Tampa Bay -- the city itself has only about 4.6 people per acre. Rather than build up, in 1988, Tampa annexed 24 square miles to its north, filled it with low-density development and named it New Tampa (the name itself implying that "old" downtown Tampa is obsolete). The Suncoast Parkway, opened in 2001, is emblematic of the area's development, and one reason why the region's growth is mostly occurring 50 miles away. Downtown Tampa, meanwhile, has a windswept, desolate feel outside of business hours. "It still suffers from CBD (central business district) syndrome," says Bassett. "People come to work and then leave. To me the city is rural-urban. Not to the extent of Detroit, but kind of comparable."

Without a downtown that bustles beyond the 9-to-5, "America's Next Great City" has fallen to last place among six nearby economies as measured by the Tampa Bay Partnership's economic scorecard. The median family income in Tampa Bay (which includes St. Petersburg and Clearwater) is $55,700, lower than most others in the region. And business owners are starting to panic that letting the city go to pot will start impacting the tourism industry. "Behind the scenes, [business leaders] have discussed the need to provide 'political cover' for elected officials interested in working toward infrastructure investment," reported Tampa Bay Online.

Some of those elected officials, especially the ones in the city proper, are doing their best to push through improvements even as their countywide counterparts just say no. Mayor Buckhorn, elected last year, spoke in July at a Politico-hosted discussion about the RNC, and talked about the need for the city to transform both physically and philosophically. "It's a city that's trying to change its economic DNA from real estate and tourism to a more technological, value-added economy," he said. "I've got a 6-year-old and an 11- year-old ... and if I want them to come home someday, and not go to Austin, Texas, or San Diego or to some other technology center, I've got to create an environment that allows them to come home to a job that wants the education my wife and I are going to give them."

On that front, the city has been talking up two marquee efforts. The first is the University of South Florida's new Center for Advanced Medical Learning and Simulation. Billed as the largest facility in the world that allows med students to practice surgery without a patient, the $38 million facility, right downtown, hopes to draw 60,000 people to the city each year. The other is the Riverwalk, which will open up the Hillsborough River with 2.6 miles of green space. In June, the city received $11 million from the Obama administration to finish the project. Already, the Tampa Museum of Art has relocated there, alongside a new eight-acre park that stages live performances and events. Yelp reviewers have been gushing with gratitude for the desperately needed public space.

Buckhorn's predecessor, Pam Iorio, also worked to get more residents downtown, but the housing collapse -- which hit Florida hard, and Tampa in particular -- slammed the brakes on much of that. "Before the downturn hit, very substantial pieces of downtown had been redeveloped," says Gary Sasso, president of the legal services outfit Carlton Fields and former chairman of the Tampa Bay Partnership. "That's starting to come into its own again. I think there's a real demand for that here. It's very exciting and I think will launch an era of prosperity in Tampa."

Bassett isn't so sure. Two years ago, when Rick Scott sent back the $1.2 billion that President Obama had allotted for Florida's high-speed rail, she got the idea for a contest called [Re]stitch Tampa. Entrants conceptualized public spaces along the new Riverwalk, which, while ambitious, seemed to Bassett to suffer from the design issues that often plague Tampa's attempts at better urbanism. "The city does have design guidelines, but in this economy they'll usually give in to what the developer wants. There was a law firm asking if they could keep their parking lot on the Riverwalk, and it's like, no, it's not OK to have a parking lot on the Riverwalk! There's no large-scale vision for the civic realm." Indeed, many of Tampa's efforts have either seemed too small -- a bike lane here, a sidewalk there -- or large, but not exactly current. "We do spend public money," says Kerstein. "They built the convention center, the aquarium, the baseball stadium," (the last of which, Tropicana Field, is in St. Petersburg.) One doesn't sense an overarching plan.

And that may be exactly how some of the local political leaders want it. Plans cost money, require collaboration, and stink of an elitist plot in which the government's guiding hand quashes our freedom to grow as un-smart and un-sustainably as we want to. There are people in Tampa who want to improve the city -- it's worth noting that even though the light-rail tax was overwhelmingly rejected by the county at large, a majority of the city's residents voted yes. And Mayor Buckhorn's 2013 budget proposal, unveiled this month, manages to scrape together $100 million for capital improvements to public amenities.

But Tampa can only do so much thanks to a toxic combination of hostility toward government, revenue and collectively used amenities. What's the matter with Tampa? The Republican conventioneers will get to see for themselves when they arrive. Except that some of them will be staying up to 90 miles away from the convention venue. "Tampa's reeeally spread out," the host of the Politico discussion observed to Mayor Buckhorn. That it is. And because of this, the city has chartered over 400 buses to move the convention visitors around while they're there. It's an inconvenient, makeshift, make-do solution -- the kind that's necessary when you don't plan and don't invest -- and a cautionary tale for America at large should a Romney-Ryan ticket reach the White House.

Shares